A WEIGHT OF ALBATROSS

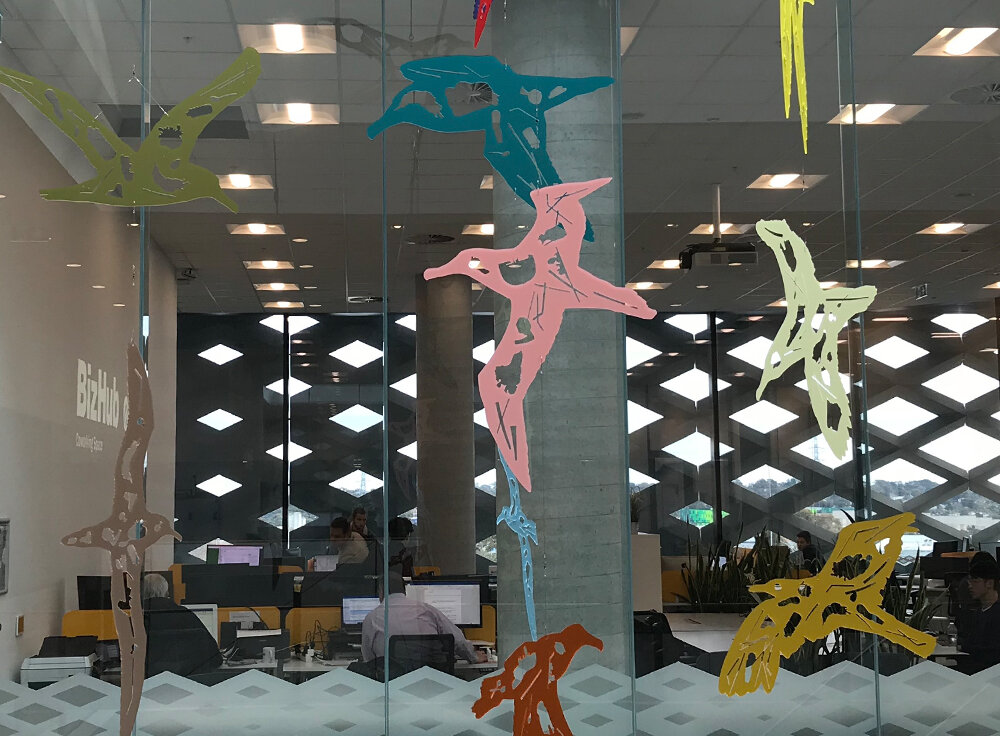

A commission, currently in flight, for Realm.

Gracia Haby & Louise Jennison

A Weight of Albatross

2018–2023

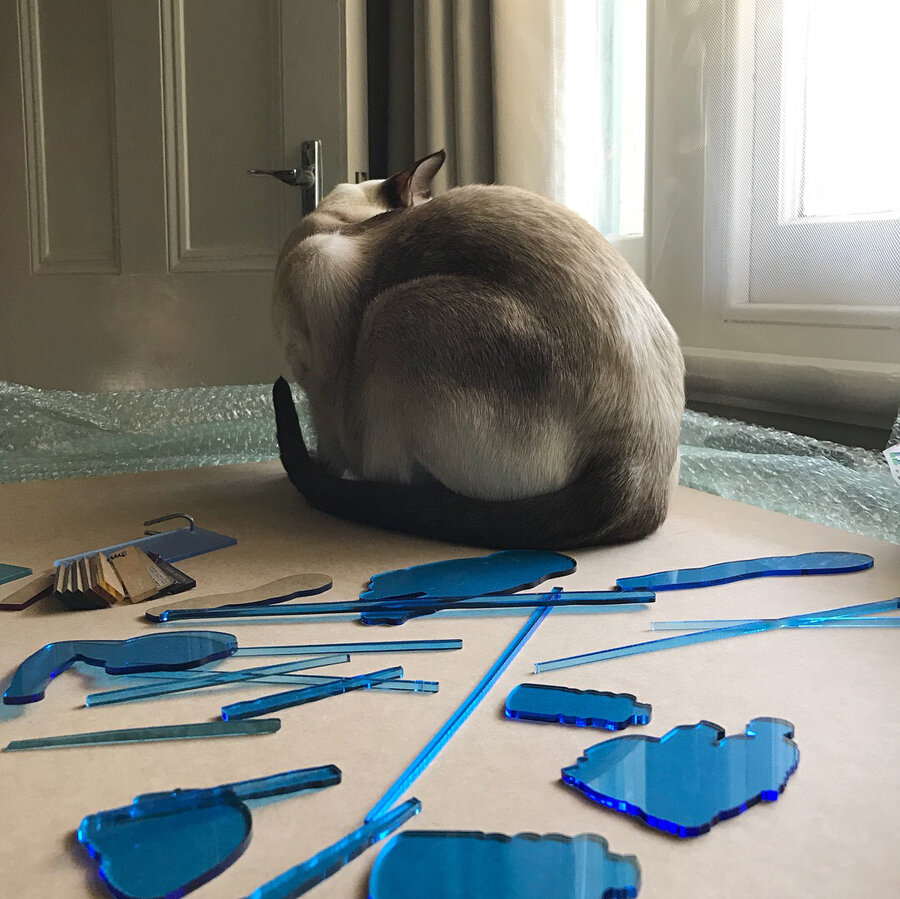

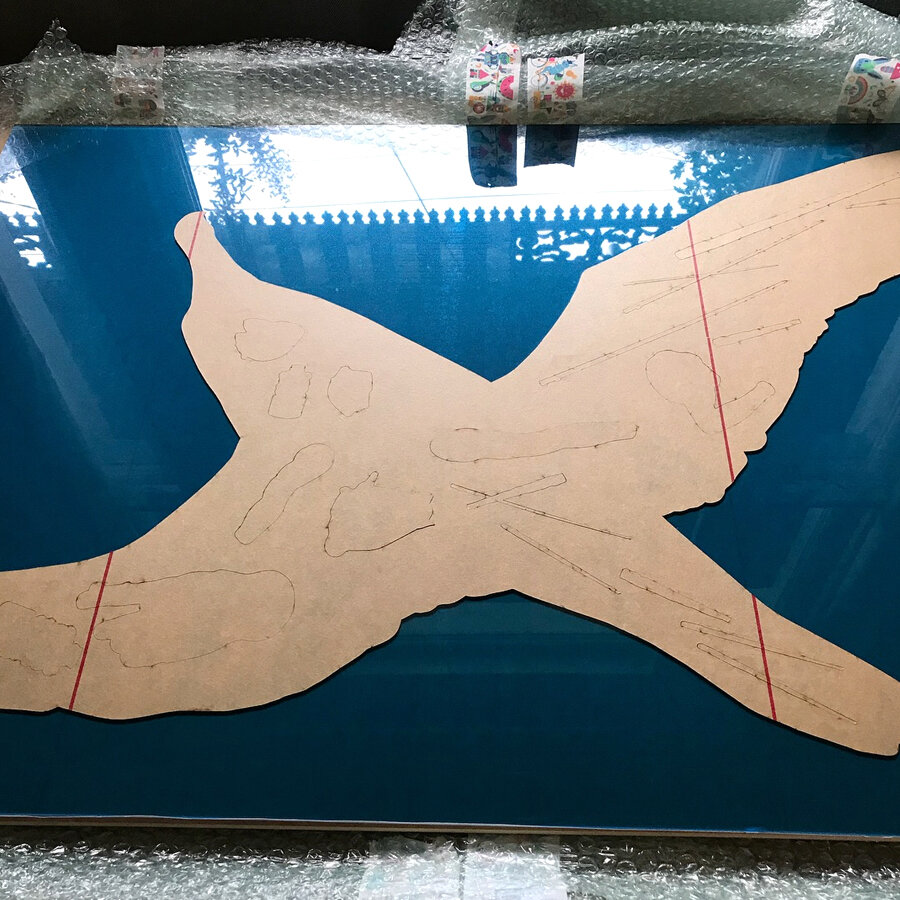

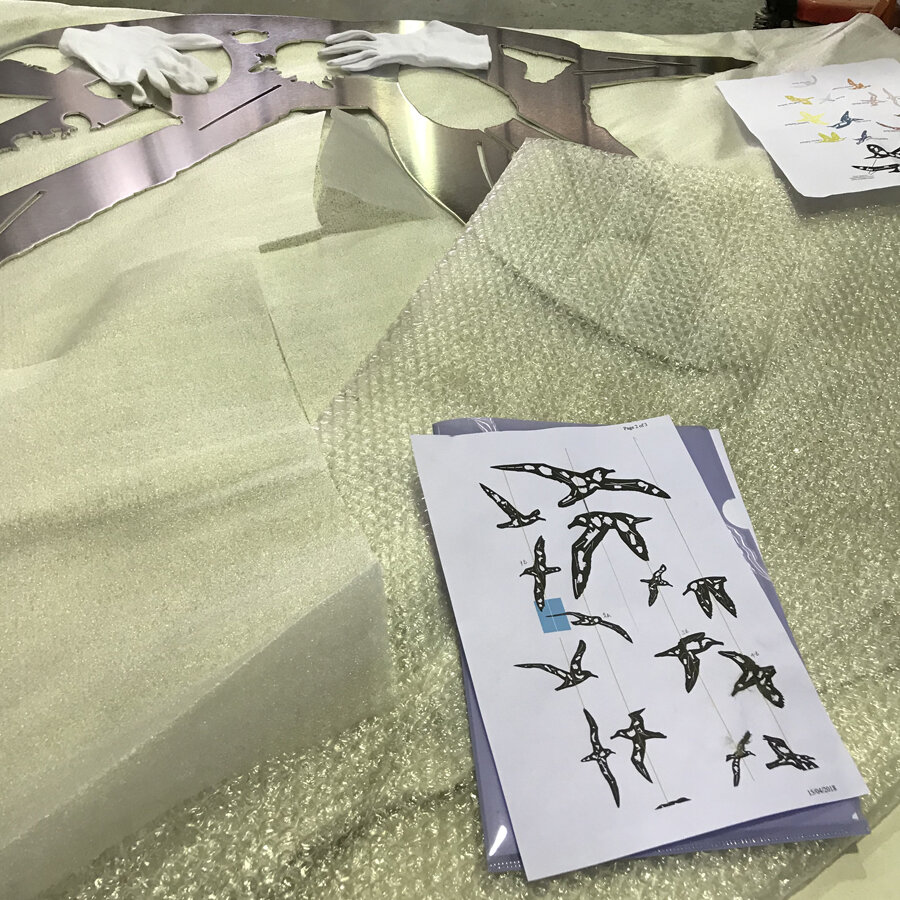

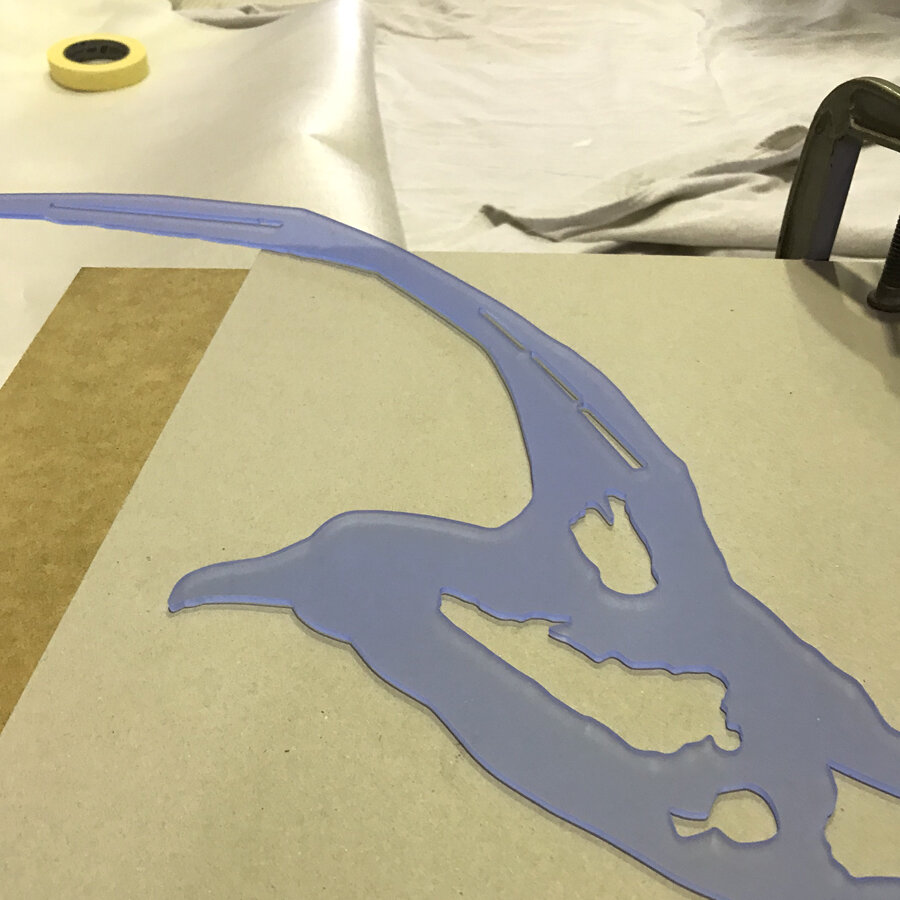

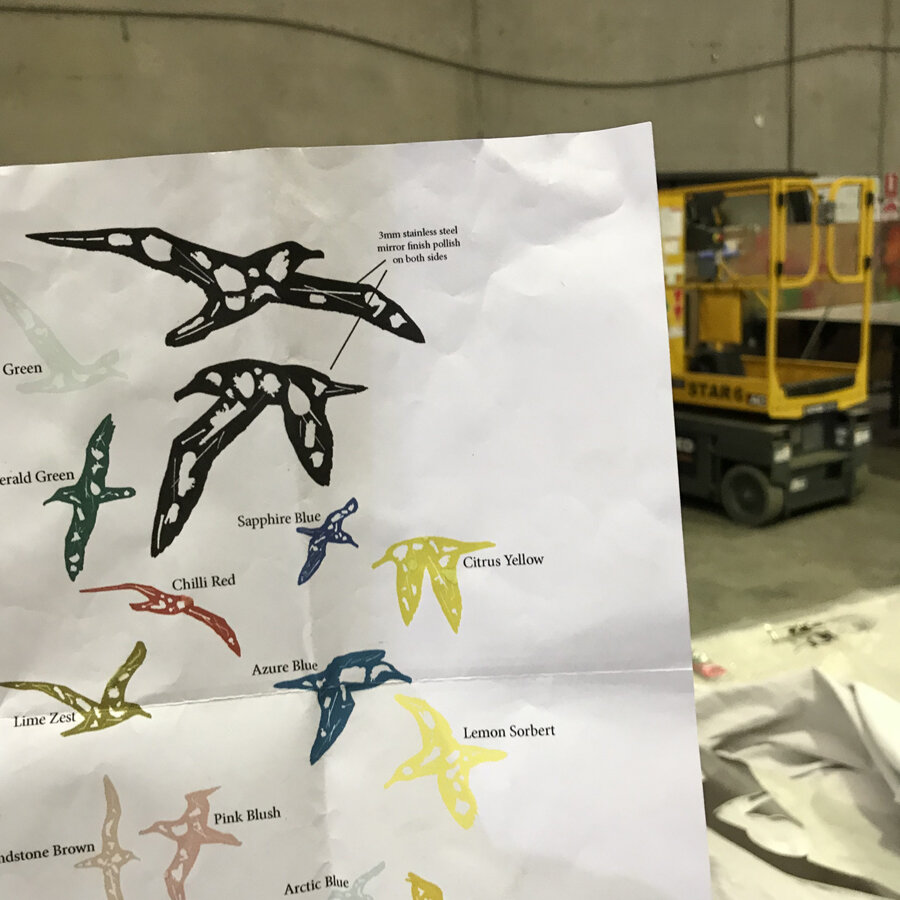

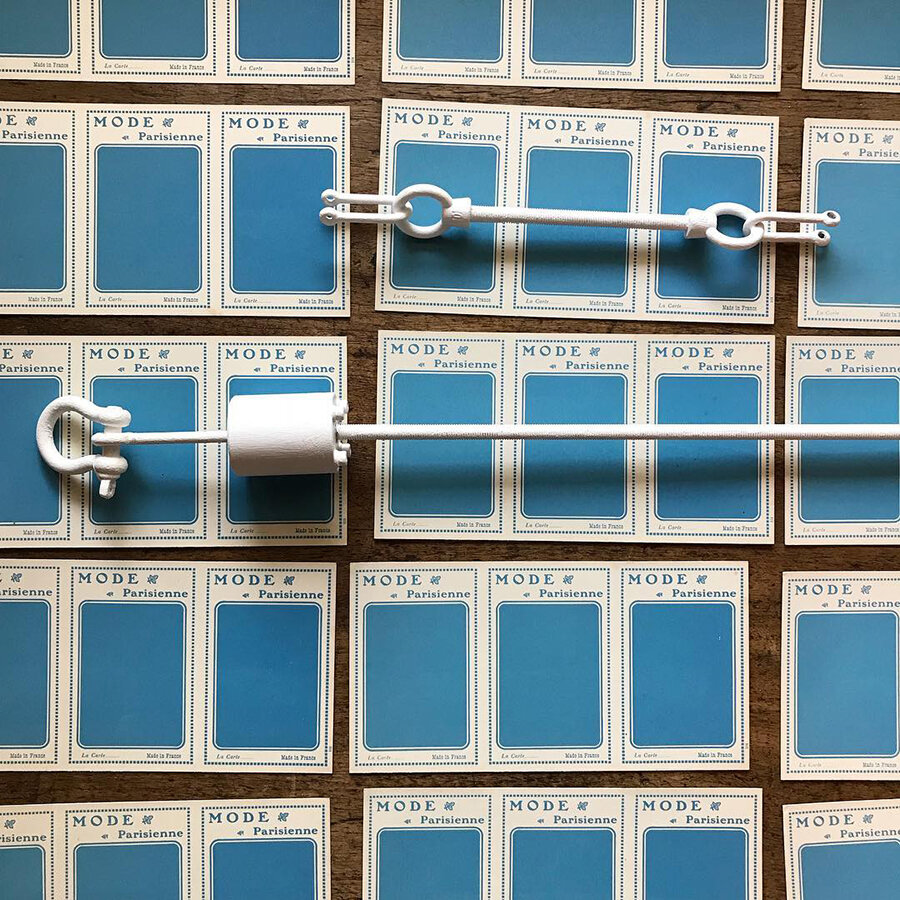

Steel and acrylic

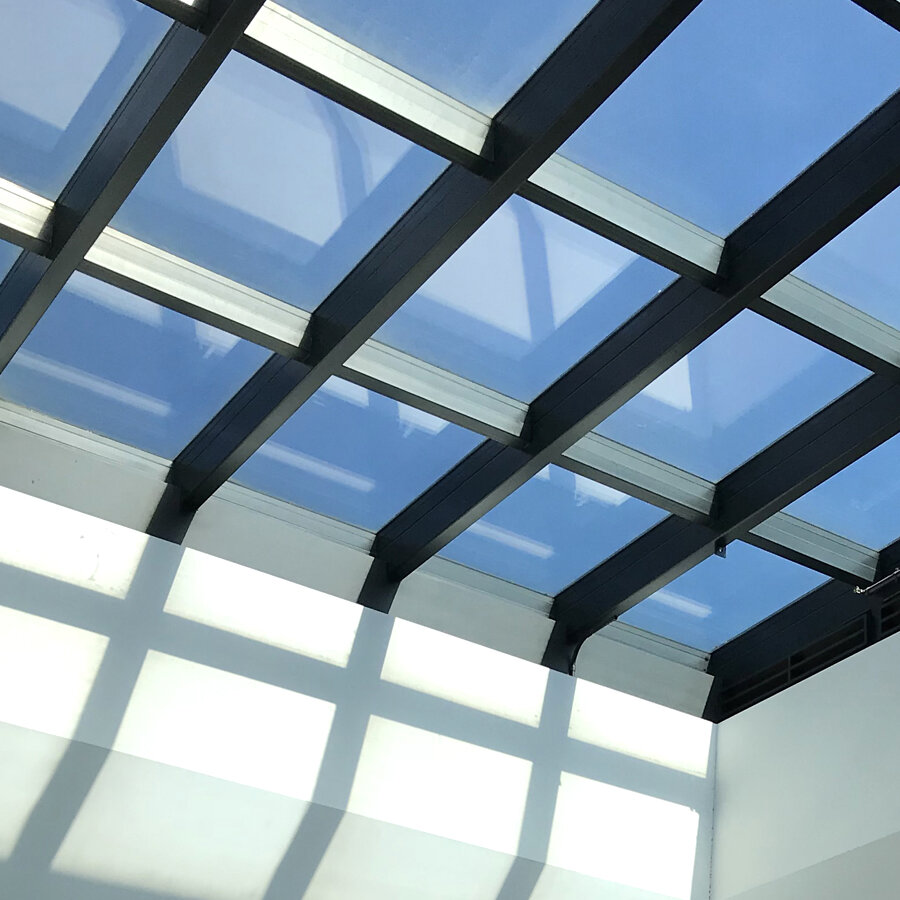

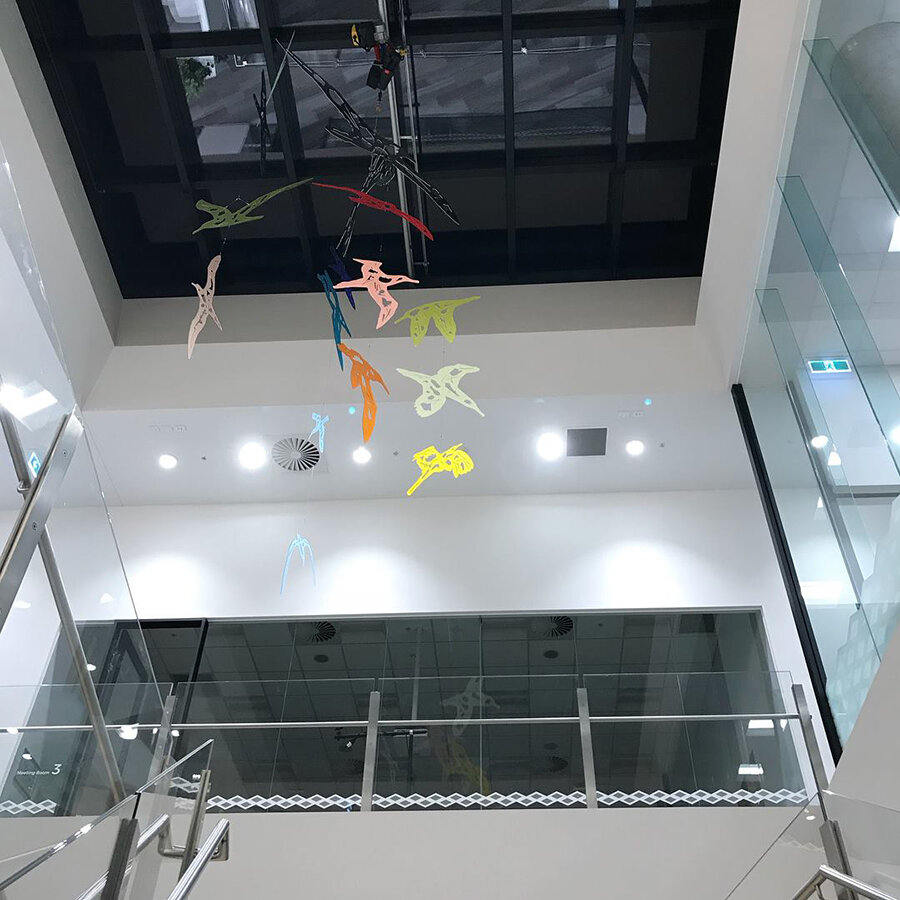

Realm Maroondah City Council’s new library, cultural, knowledge and innovation centre Ringwood Town Square, Victoria

Extended indefinitely (2023)

“We’ve seen albatrosses come back with their belly full of food for their young. You think it’’ going to be squid, but it’s plastic. That chick is going to starve and die.”

●

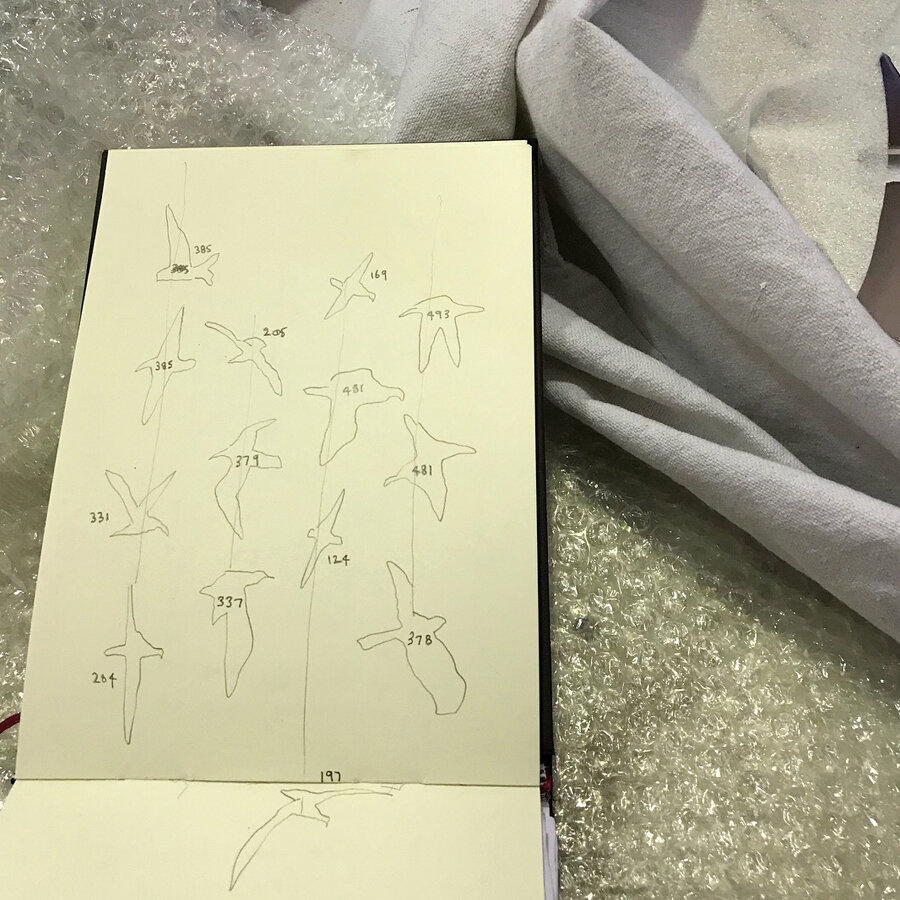

Included in our weight you will find a Wandering albatross (Diomedea exulans), Southern royal albatross (Diomedea epomophora), Laysan albatross (Phoebastria immutabilis), Black-browed albatross (Thalassarche melanophris), Shy albatross (Thalassarche cauta), Grey-headed albatross (Thalassarche chrysostoma), Indian yellow-nosed albatross (Thalassarche carteri), Sooty albatross (Phoebetria fusca), and a Buller’s albatross (Thalassarche bulleri).

﹏

RELATED LINKS,

#AWEIGHTOFALBATROSS

A WEIGHT OF ALBATROSS, INSTALLED AT REALM (UP! UP! UP THEY GO TIME-LAPSE VIDEO COURTESY OF CITY OF MAROONDAH)

MAROONDAH CITY COUNCIL

RELATED POSTS,

UP!

“THE WHOLE IS OTHER THAN THE SUM OF ITS PARTS”

“THE POETS ALMOST REMIND ME OF THE TRUMPETERS”

A WEIGHT OF ALBATROSS

A Weight of Albatross at Realm

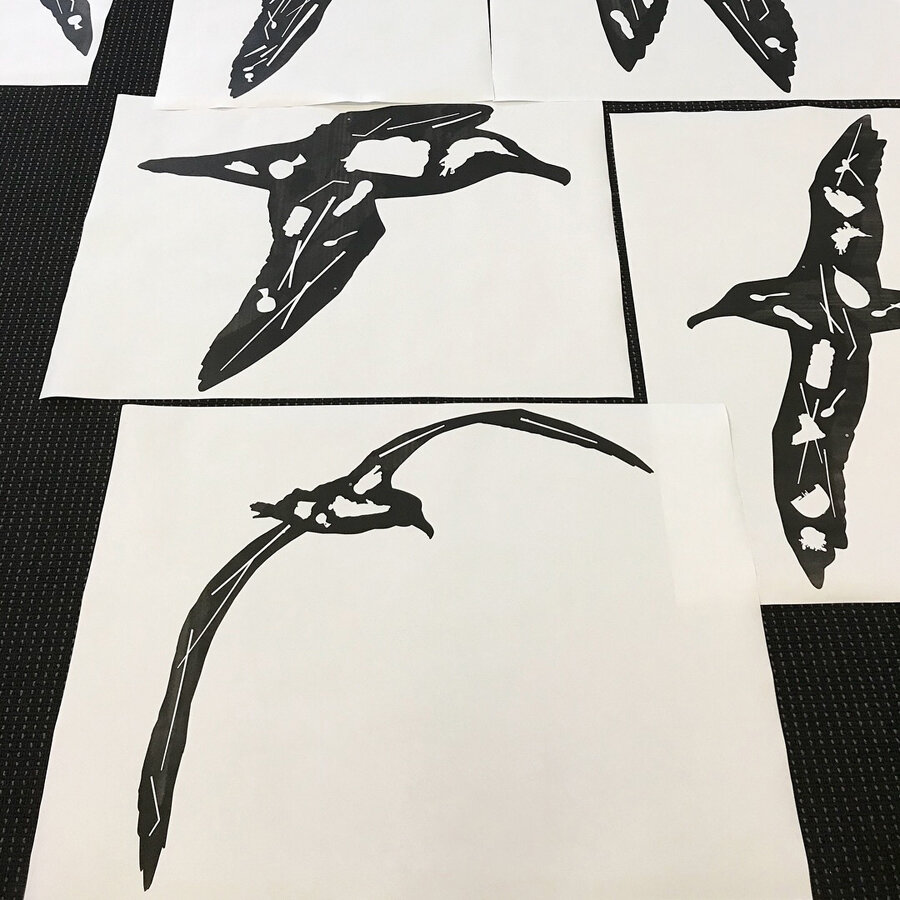

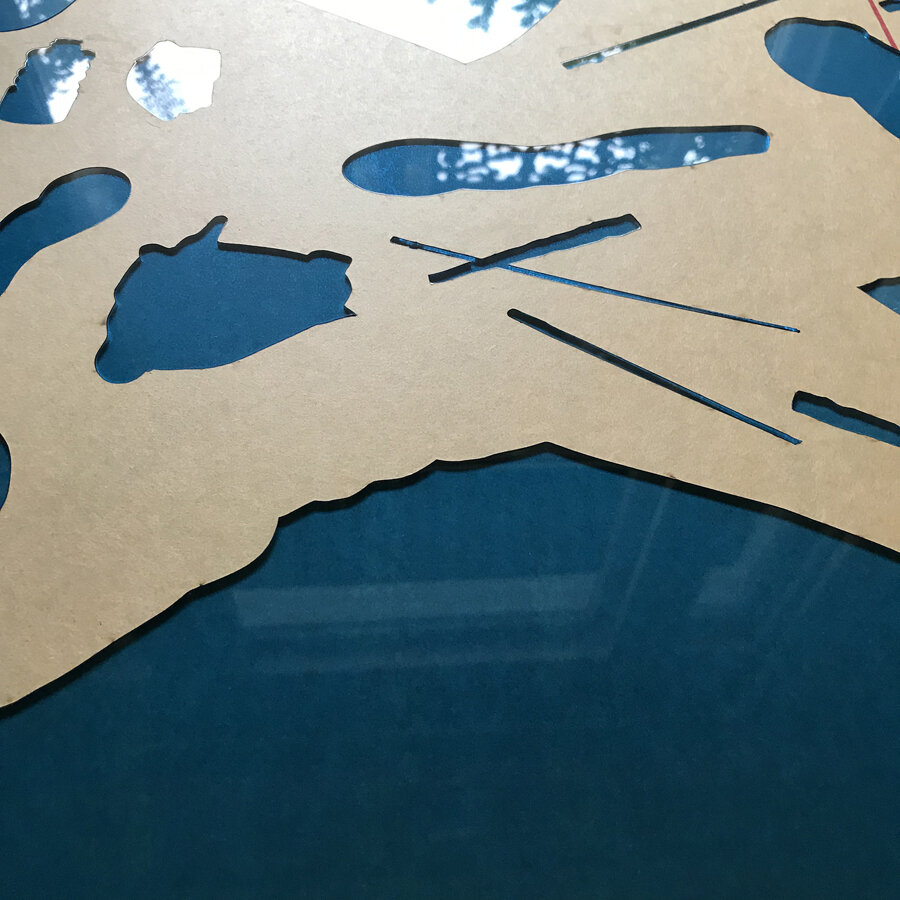

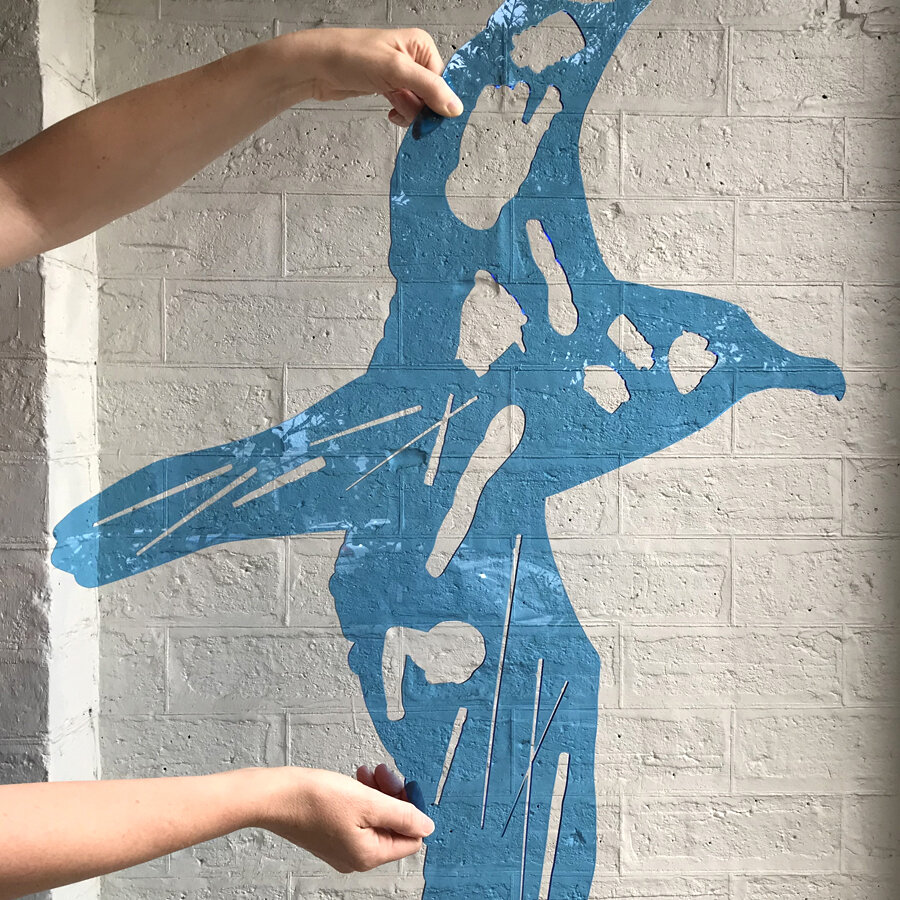

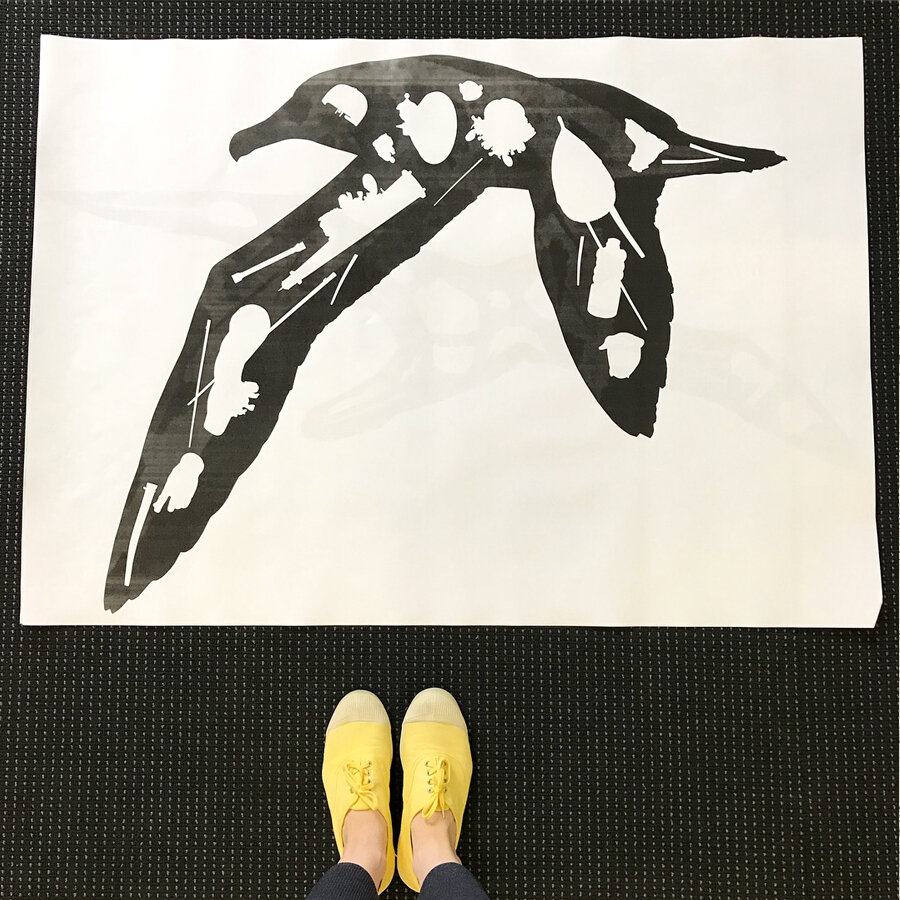

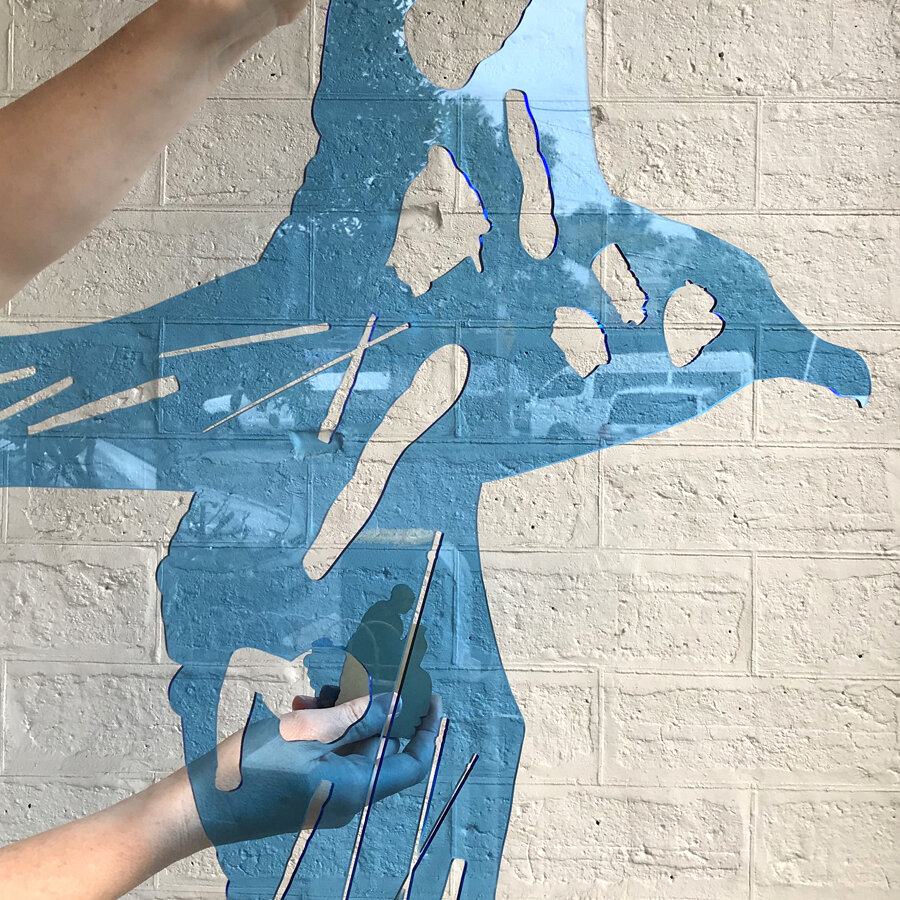

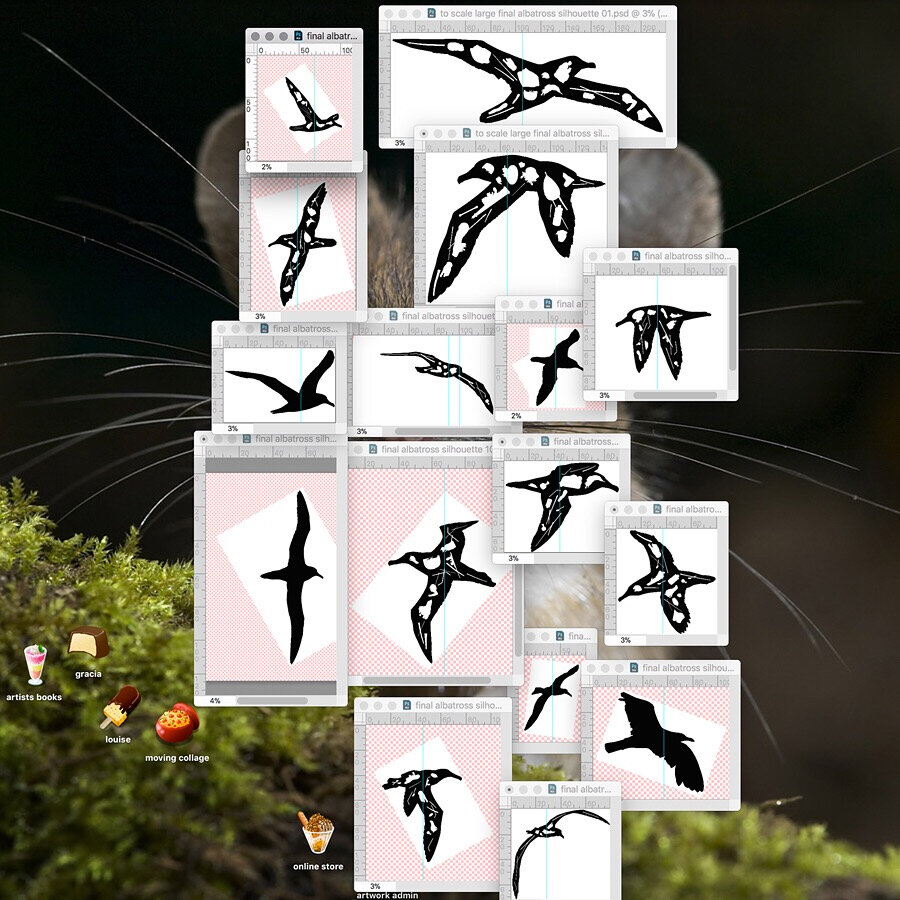

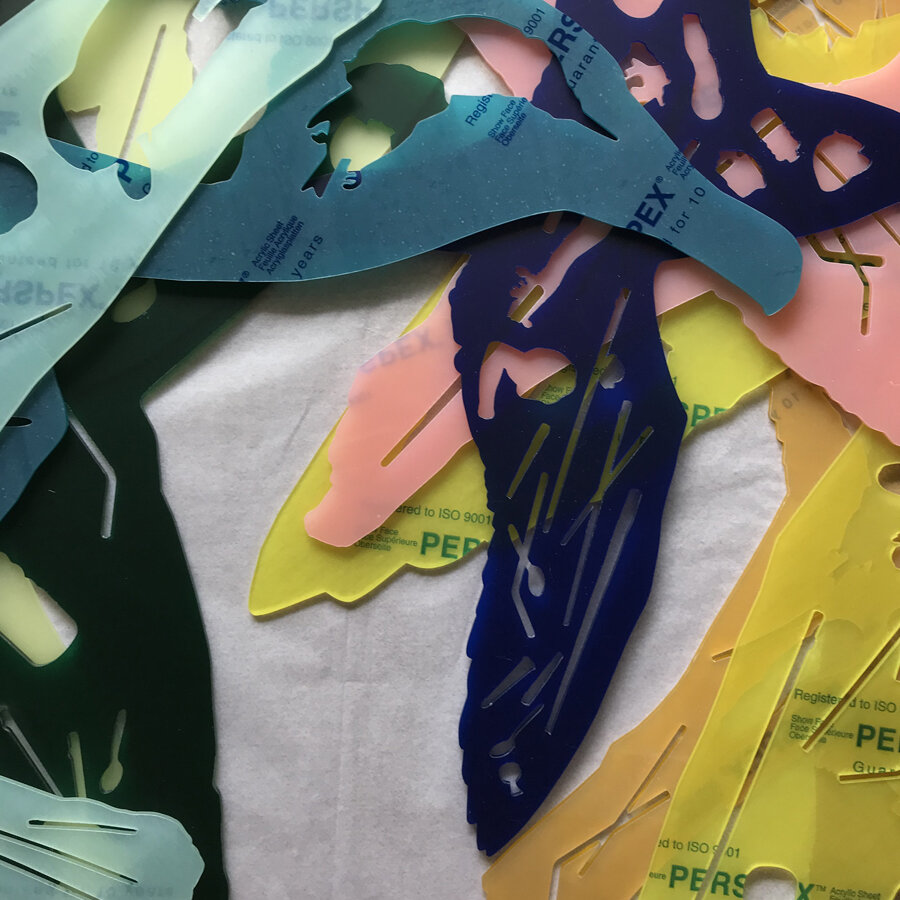

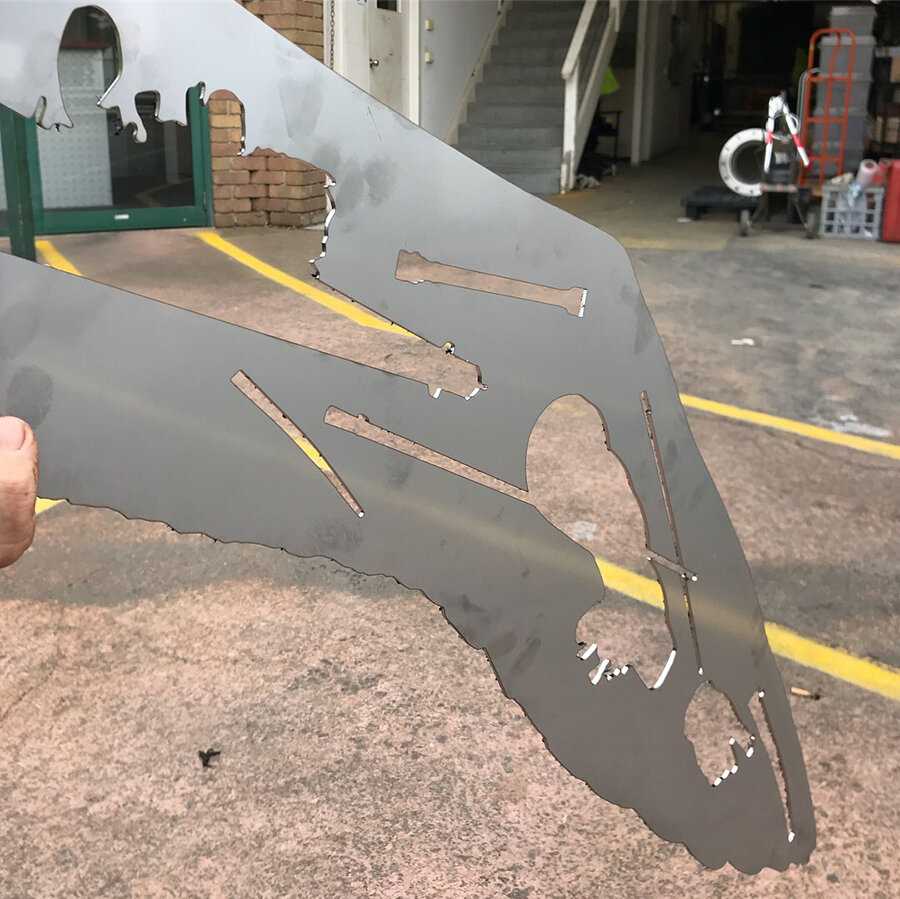

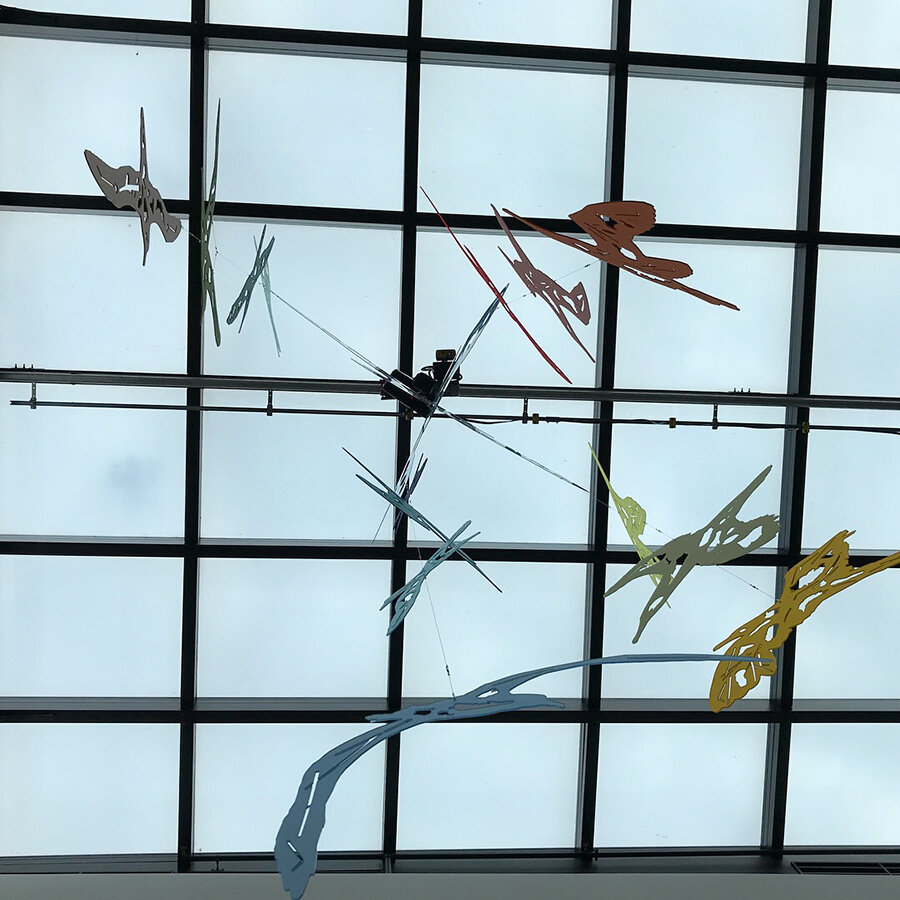

Treating sheets of acrylic and stainless steel as if they were large sheets of paper, we have laser-cut giant collage pieces in order to create a swirl of movement, a treasure of colour, a collection of jewel-like silhouettes, a flight, soaring, above the Realm staircase.

The most common collective noun for a group of albatross is a rookery, but a weight is also accepted, and though the OED preferences albatrosses as the plural, Collins and Merriam-Webster are happy to fly with albatross. So a weight it is, A Weight of Albatross, because it sounds more poetic to our ears. A Weight of Albatross, a commission, currently in flight, for Realm. For 2018, and beyond.

What at first glance might appear as the directional strokes of feathers or internal framework, resolves as a tangle of shapes evocative of plastic debris ingestion.

With the highest concentration of plastic in birds found in populations in southern Australia, South Africa, and South America — where coastlines are closest to loosely-concentrated collections of ocean debris in the southern Pacific, southern Atlantic, and Indian Oceans — our soaring albatross reveal the plastic they have ingested, including “bags, bottle caps, synthetic fibres from clothing, and tiny rice-sized bits”[i] because “some seabirds eat so much plastic[ii], there is little room left in their gut for food, which affects their body weight, jeopardizing their health…. [and fragments of] sharp-edged plastic kills [the] birds by punching holes in internal organs”.

Alongside straws and lids, our shapes include several antiquities. In one majestic seabird you’ll find a 3rd–2nd century B.C. bronze statue of Eros sleeping alongside a plastic spoon. In another, some of you might recognise the shape of a certain netsuke mouse (from Looped), and ornate columns from the hills and valleys of our artists’ book No longer six feet under. Something beguiling, we hope, but also something to make you think.

Notes:

[i] ‘Nearly Every Seabird on Earth Is Eating Plastic: Plastic trash is found in 90 percent of seabirds. The rate is growing steadily as global production of plastics increases’, Laura Parker, National Geographic online, accessed 12th February, 2018.

[ii] “The effect of plastic ingestion on seabirds in particular has been of concern …. due to the frequency with which seabirds ingest plastic and because of emerging evidence of both impacts on body condition and transmission of toxic chemicals, which could result in changes in mortality or reproduction. Understanding the contribution of this threat is particularly pressing because half of all seabird species are in decline. Plastic pollution in the ocean is a rapidly emerging global environmental concern, with high concentrations (up to 580,000 pieces per km2). Seabirds are particularly vulnerable to this type of pollution and are widely observed to ingest floating plastic.”

‘Threat of plastic pollution to seabirds is global, pervasive, and increasing’, Chris Wilcox, Erik Van Sebille, and Britta Denise Hardesty, ‘Proc Natl Acad Sci USA’, issue 38, 22nd September, 2015.