THE BIG ISSUE, 2020–2022

1/ Gracia Haby & Louise Jennison

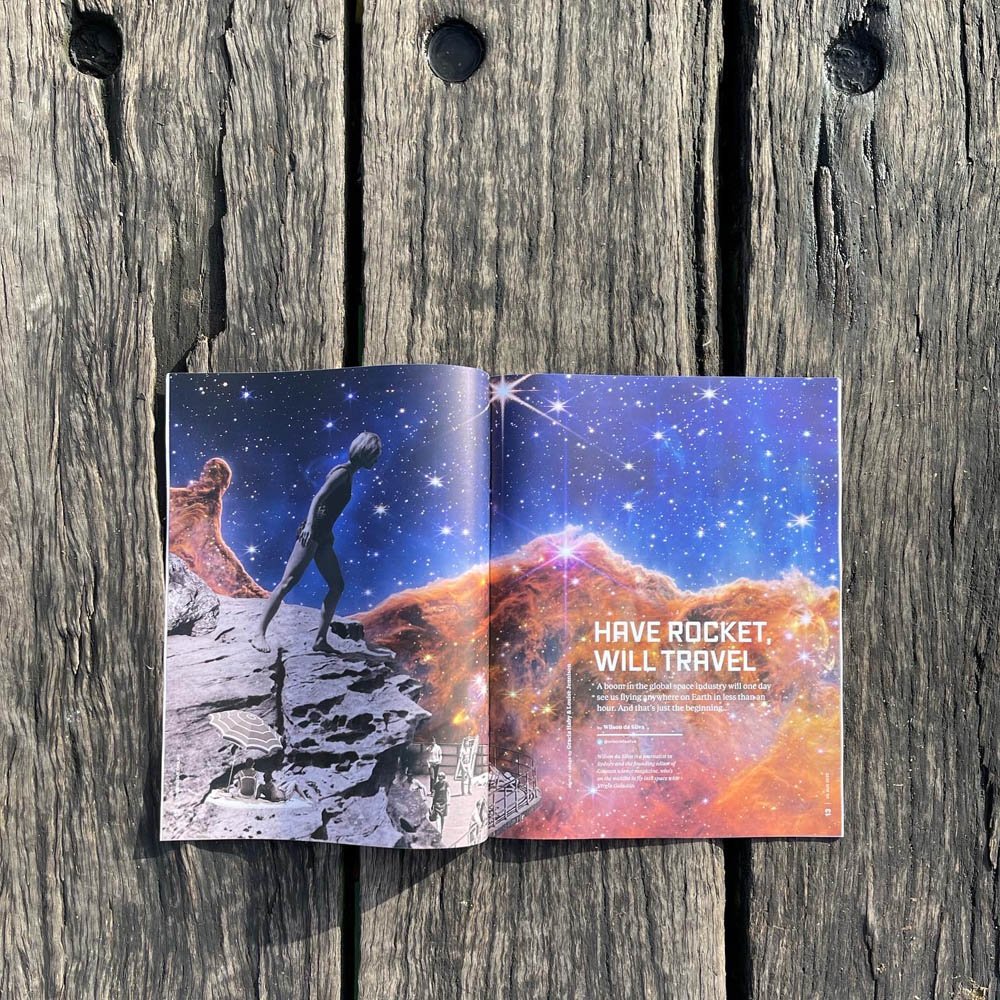

Have rocket, will travel

2022

Collage created for The Big Issue magazine

Space Travel

No 667

5th of August – 18th ofAugust, 2022

A collaborative collage created to accompany Wilson da Silva’s ‘Have rocket, will travel’ article on pages 12–15.

Our eleventh digital collage commission for The Big Issue, this time featuring the Cosmic Cliffs in the Carina Nebula, as captured in infrared light by NASA’s James Webb Space Telescope.

﹏

RELATED POSTS,

SEVEN LIGHT-YEARS HIGH

HAVE ROCKET, WILL TRAVEL

Q & A

Q & A

Answered for Mya Cook

As part of Art Enterprise Workshop,

Bachelor of Arts (Fine Art), School of Art, RMIT University

15th of August, 2022

As collaborators and as individuals, engaging in the limitlessness of paper as you have, the both of you have been prolific in creating your portfolio of work over the years. How do you think your work has evolved since your studies at art school?

Upon first thought, our work now responds to a specific space, or theme, in the case of commissions, however, this could also be said of our work previous, while studying painting at RMIT. Deadlines still need to be met, so, too, a series of requirements. Hmm, let’s see. Now versus then, how has it evolved? A clearer message. Yes! We’ve become better at editing. The distillation process! At not throwing all our ideas into the one work. Refinement, that could be it. Refinement through never being too afraid to start over if something is not working; to adapt plans depending upon what arises. To make our voice have purpose. Specifically, in regards to nature, and our responsibility to reciprocate.

Are there any key moments or stepping stones that stand out to you in having led you on the journey of your career?

We treat all opportunities, the tiny to the grand, in the same manner. They are all important in their own way, and they all fed into each other. This being true of all things. Opportunities to play with scale, like our 15-metre-long wall collage, Ripples in the Open. Opportunities to try new materials, like A Weight of Albatross in a stairwell. Opportunities to create a series of collages to describe someone else’s music, like Bower for Genevieve Lacey. Opportunities to install our artists’ books in the dais of State Library Victoria in the early morning before the library opened.

Together they form a mycelium, if you like. A network of ideas, beneath the surface, connecting, growing, flowing into the next. What you learned. What ideas it untapped. What conversations arose. What matters to you.

All moments kind of become key moments. When you pause, take stock, rearrange your feathers, and grow on.

Were there any goals you set out with upon leaving art school?

To keep making. Always. And regardless of the spacing of those stepping stones you mentioned above.

Is there any advice that you would offer emerging artists today? Perhaps that you did, or wish you had received during your studies?

Keep making, too. If that speaks to you. And give all accepted opportunities everything. The ‘size’ or deemed ‘importance’ of the project does not matter. Authenticity of voice, to us, matters more.

Make to make a difference, in a nutshell.

Has there been a clear trajectory for you throughout your career, or is the process of creating more organic for you both, as issues and subject matter that you choose to explore and respond to emerge?

It feels more organic, yes. From in the thick of it, that is. No part is created in isolation. What we learn from one we take into the next. And when the gaps between the stepping stones feel too large, we devise a self-directed project. A zine. A series of digital collages for a post. Anything. We keep following the ‘keep making’ path.

We remain open to things not having a known outcome, and, as such, different things arise.

Thanks to the recently retired Rare Printed Collections Manager, Des Cowley, we have seen incredible and varied treasures in the collection of State Library Victoria, and this is also something which shaped the river in the sense that it opened our minds to what was possible then, and is possible now.

The same could also be said of creating a series of eleven lithographs and etchings with The Australian Print Workshop, as part of their French Connections project. We drew a collage on the plate, and felt our way along. With the plates then exquisitely printed by Martin King, we didn’t need to worry about how to achieve a print within our grasp, and could let ourselves be untethered, which is a wonderful rarity. As such, a single-colour lithograph grew into a three-colour lithograph, and we quickly had to learn on our feet how to layer colour.

I’m also very curious to know more about your commission works. They’re so varied in subject matter, let alone format and scale, from Ripples in the Open, to those within publications such as The Big Issue. Could you describe the way that some of these have come to fruition?

The idea behind Ripples in the Open was to make a work that would invite people into a space they might normally feel uncomfortable in or race past en route to the lifts. In ArtSpace Realm, beside a café, and beneath a library and a community business hub, we wanted to make something that was just that, inviting. A colourful lure. With the lenticular prints dotted throughout the scene, the enticement, we hoped, that you’d walk the length of the collage to see the animals within each print move. We opened the front walls as far as we could so it was a place where many would feel comfortable. Working with the space being one that didn’t have someone sitting it, we also wanted to make sure the work could look after itself. You could run at this vinyl wallpaper, stroke it, even pose before it.

To create a collage large enough, we looked to wallpaper and the means of repeat. We scanned images from library books, and made one tulip multiply into twenty tulips, fifty petals, eighty. As you could stand beside the work, nose to petal piece, we needed to make the work at a resolution we’d use for a book (as opposed to a billboard seen in the distance). We made a landscape of many pieces stitched together as a whole. Just like our trajectory, just like those key moments. We can make something big, physically, not by ballooning something, but by making many small, manageable pieces, and melding them together as a big, united whole. We saw the landscape as a theatre set. We dropped in a mountain of tulips behind a lake, by a grass plain cobbled together from wild mangoes on repeat. We liked the idea of being able to rebuild something different to its original source. And animating the taxidermy specimens from a Long-nosed potoroo to a Polar bear.

For a collage for The Big Issue, we begin with a similar palette of many pieces. Some that seem a good, literal fit, and others more obscure, perfect for a background or a shirt that might become the sea. We have created eleven collages for The Big Issue. Typically, we receive a copy of the text we need to illustrate. Our most recent one, in the current issue, features the Cosmic Cliffs in the Carina Nebula. Our task: to depict space travel for the everyday person. It’s coming in fifteen years.

As ever, we create a series of collages for them to pick from. Partly because the turnaround is tight and this will give them options and make their printing deadline achievable. And partly because we treat it as a chance to push ourselves and play. Some of the themes in collage commissions are ones we have an affinity with, and others are a different kind of challenge. A battery, a dog, some silverbeet. Sure. We also like seeing which one they’ll choose to publish. It serves as a different kind of feedback.

What links these two different types of commissions is that we want to communicate with people. With whoever is looking at the collage on the wall or in The Big Issue. We don’t want to be too obvious/literal, and dampen play and the chance to ponder and dream, but we don’t want to exclude anyone. We don’t want to talk in bubble.

For yourselves, what are some avenues that have led to these projects emerging?

Word-of-mouth. Always meeting a deadline, if it is a commission for a publication or cd. Keeping busy in the quiet periods. Nothing ever paces itself well. There are many ‘all at once’ moments, and quieter ‘what’s the point?’ patches that could be more kind in their arrangement, but, hey, that’s not how it works.

And, as mentioned earlier, always giving whatever the work, big or small, our full attention. There is a lot of noise out there, and we don’t want to contribute just any old thing and make more noise. It should mean something. That’s something a lot of us are chasing, isn’t it?

For myself, the use of the found image is always exciting in the ways that re-contextualising these images may create new meaning, ultimately adding to their stories and giving them new life. What is it that draws you to the found image?

Snap! Absolutely. What’s not to love about new meanings springing before your eyes on the page or screen. The unexpected, we love that too. The surprise as you move a piece and suddenly it falls into place and it is not anything like where you thought you were heading. When so many things are planned, this feels especially nice. The chance encounter, but orchestrated at its base.

Images of fauna often appear within your work, and you’ve also taken on the amazing roles of fostering both cats and native animals alike from the RSPCA and Bat Rescue Bayside respectively. Would you describe the relationship between these interests outside the world of art and the work you produce as seperate or homeostatic?

It’s all one, all glorious one, of course. It was as unintended as our trajectory. And yet it feels like it was always meant to be this way, no matter the path, the circumstances, the chance encounters.

Fostering for the RSPCA has been such a rewarding experience for us. It makes sense of things. Of how you can help. It gives purpose. And you get to meet so many different cats in the process. It is the same with cat or a collage in that you get to learn through doing. You need to earn their trust. To be in their time. To let them be themselves. Some have been mistreated by humans, or are in recovery from surgery, or need a calm environment, a break from the shelter. We’ve nursed a beautiful cat, Chocolate, our seventh foster, who had burns to her head, neck and spine. We’ve learned to go slowly. And as we work from home, we can easily fit in looking after a foster. All they need is a designated safe house. Your time. Your patience. Your company. And slowly, they heal, the lucky ones.

If fostering for the RSPCA is a natural extension of the things we are interested in talking about, in our work and life, becoming wildlife carers, three-years-ago now, seems inevitable. Our lockdown walks through the Grey-headed flying fox colony at Yarra Bend saw to that. We could do more. We should do more. Instead of just making works about animals and nature, and taking from that which inspires us, we could become wildlife foster carers. And so we did.

We have an outdoor soft-net enclosure for the flying foxes. We have an indoor one for when they are small pups. We have an incubator for when they can’t self-regulate their body temperature. We have a smaller wire enclosure for housing four ringtails or an adult, too. We have the time, the space (just about), and we are keen to learn more. To help nurse little orphans, like last season’s Remy and Pip. To help get them back into the wild where they can do all of the incredible things flying foxes do.

Why shouldn’t all these things bubble alongside each other. They nourish each other. It is also a wonderful experience to be in their presence. To be up close to them, and in doing so, enter another domain. Their realm. To read and experience how they do things. To be less ‘you’, and more a small piece in a whole. It is a huge privilege to be in their company, their way.

Has this relationship evolved over time?

It has and it will only become more so. The ratio may change, seasonally, or otherwise, but it will only become more entwined, enmeshed. We are foster carers now, but next year, we plan to apply to have our own tiny shelter. Run from our home. With room for a handful of orphaned pups, and whoever else presents. Yes!

The use of the found image can talk to a delicacy and fragility that is gained over the passage of time; characteristics which are also present within the living world. How would you position your work within wider conversations of ecological conservation and preservation?

We want to speak with a positive voice. To encourage action. We want to highlight what can and should be done. Flying foxes are endangered, and we may live to see their extinction. Yet they are our forests. Those beautiful pollinators are everything. We want people to call a wildlife rescue group when they see an injured flying fox. A mum who has been electrocuted when she took a rest on a powerline and her wing connected with a second line. Sometimes the pup she is carrying is still alive and can be saved. We want people to think about flying foxes in a positive light, to be less fearful of them. To remove dangerous fruit-tree netting. So, the answer, attention. We’re seeking to draw attention to these incredible animals. To habitat loss. Biodiversity loss. We’re asking people to pause, reflect, act. To observe. To recognise that their needs to be less take, take, take.

What would you say is paramount that you are trying to communicate to your audience?

Reciprocate with nature.

With your use of the found image, I imagine that you must have quite the collection of your own that you have sourced over the years, so much so that it must be difficult to recall. In light of this, when compiling any images into a work, how does your process begin?

Each project has its own palette. So that we don’t keep repeating ourselves. And because the image sourcing is a quiet fermentation process. As you comb through digital archives, for example, thinking of a particular this or particular that, you ‘see’ the image that you think you’ll make. Though this is never the case, it always ends up forming differently.

Sometimes we’ll dip in and out of earlier palettes, to use the pieces that didn’t fit the first time, but some great finds sometimes refuse to roost, no matter how often we try. The finding part is quite meditative. The analogue collage process is a little different, but along the same lines; its meditative process is in the deciding which piece goes where before it is glued.

Do you find something that catches your eye, or do you have an initial idea in mind?

After factoring in image resolution, copyright restrictions, and a commission’s brief, both. It begins with an initial idea, a purpose, and then there is the inevitable ‘aha! That’s the piece’ moment. The chance moment. The surprise. Reinvent one known this into something else entirely. Alter the proportions, nibble a bit here and there, and it all falls into place. If not, pause, check on the ringtail joeys, start again. Our answers here have gone in a big circle. Everything is connected.

Thanks so much for this opportunity, Mya. So much to think about!

All the best,

G&L

Once again, thank you so much for the opportunity to interview you both.

Many thanks,

Mya Cook

Q & A

2/ Gracia Haby & Louise Jennison

Reel to Real

2020

Collage created for The Big Issue magazine

LEGO

No 610

17th of April – 30th ofApril, 2020

A collaborative collage created to accompany Stephen A Russell’s ‘Reel to Real’ article on page 32.

As ever, we created a handful of collages for The Big Issue to pick from to accompany the piece.