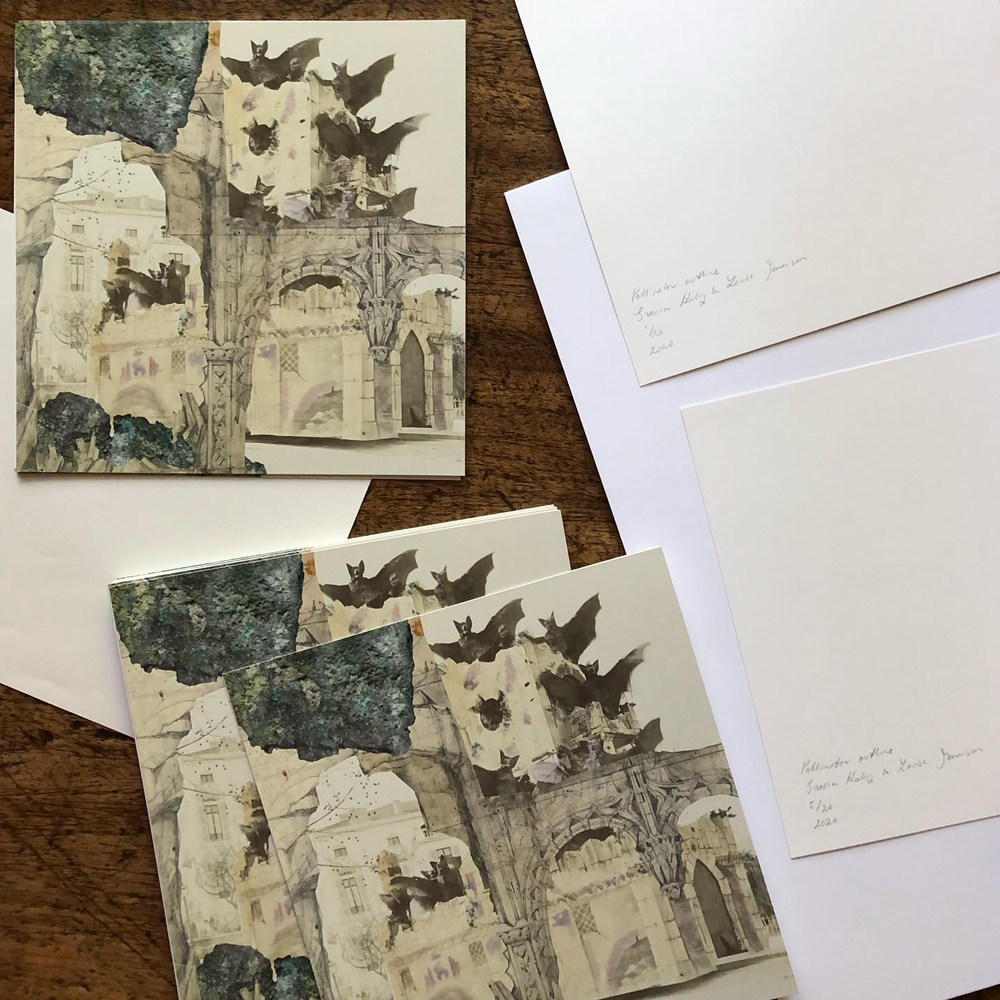

IN LOCKDOWN PROJECTS, 2020

1/ Gracia Haby & Louise Jennison

Pollinator outline

2020

For the RMIT Print Exchange Portfolio

Inkjet print on Hahnemühle Photo Rag 308gsm, 20cm X 20cm

Printed by Arten

Edition of 20, with 5 artists’ proofs

Bats, a float.

Created especially for the RMIT University School of Art 2020 Print Exchange Folio, a digital collage for those with a softness for flying-foxes, costumes, and squares.

Because without the pollinators….

The Urban Field Naturalists’ Guide to Lesser-Known Pollinators: Explore ways to tell stories about the natural world

ADAM FRANCE, CECILIA HEFFER, CHRIS CAINES, DONNA SGRO, EGG PICNIC (CAMILA DE GREGORIO & CHRISTOPHER MACALUSO), FIONN MCCABE, GRACIA HABY & LOUISE JENNISON, KATIE DEAN, LUCY ADELAIDE, ROSS GIBSON, THOM VAN DOOREN, TIMO RISSANEN, VANESSA BERRY

CURATED BY ANDREW BURRELL AND ZOË SADOKIERSKI, SPEC STUDIO, UTS SCHOOL OF DESIGN

MONDAY 15TH OF MARCH – FRIDAY 21ST OF MAY, 2021

UTS LIBRARY, UTS CENTRAL, LEVEL 7, 62 BROADWAY, ULTIMO, NSW

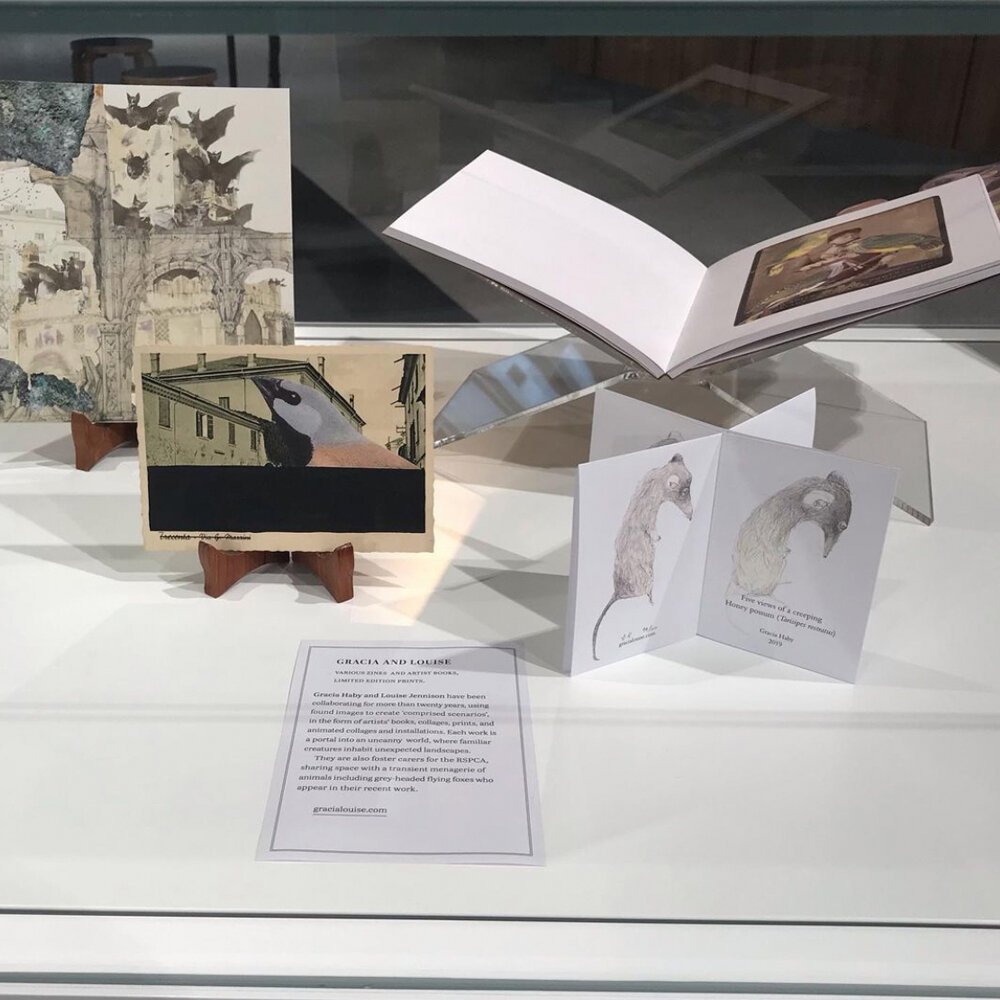

Included as part of The Urban Field Naturalists’ Guide to Lesser-Known Pollinators at UTS Library, NSW: Pollinator outline, 2020; Black-throated finch, 2019; Five views of a creeping Honey possum (Tarisipes rostratus), 2019; and Prattle, scoop, trembling: a flutter of Australian birds, 2017.

The exhibition is an outcome of the Urban Field Naturalist Project (UFN), a collaboration with researchers from the environmental humanities and life sciences.

Loosely related squares,

19 Poses for Martha Graham

#BetweenArtandQuarantine

19 Poses for Martha Graham

Recreated at a glance,

Pose #8: Frontier; Pose #11: American Provincials; Pose #1: Prelude to Action; Pose #16: Night Journey; Pose #14: Immediate Tragedy; Pose #17: Immigrant: Steerage, Strike; Pose #3: Clytemnestra; Pose #6: Satyric Festival Song; Pose #9: Spectre 1914; Pose #18: Primitive Mysteries; Pose #7: Masque from Chronicle; Pose #2: Revolt; Pose #10: American Document; Pose #5: Immigrant: Steerage, Strike; Pose #19: Errand into the Maze; and Pose #15: Frontier

#BetweenArtandQuarantine

Recreated, at a glance,

An Evening at Home (1888), Sir Edward John Poynter; Lady Shirley, in fantastic habit, full-length (Also recorded as Portrait of an Unknown Woman and Lady in white lawn masque habit) (c. 1639–51), Marcus Gheeraerts the Younger (died 1636); Breakfast with the Cat, Rudolf Epp (1834–1910); Portrait of the artist’s wife (c. 1902), Rupert Bunny (1864–1947); Portrait of a young Man holding a Dog and a Cat, Dosso Dossi (c. 1486–1542) (attributed to); Portrait of a Lady with a Lapdog (1537–1540), Agnolo Bronzino (1503–1572); and The Letter Writer (1680) (sort of) by Frans van Mieris

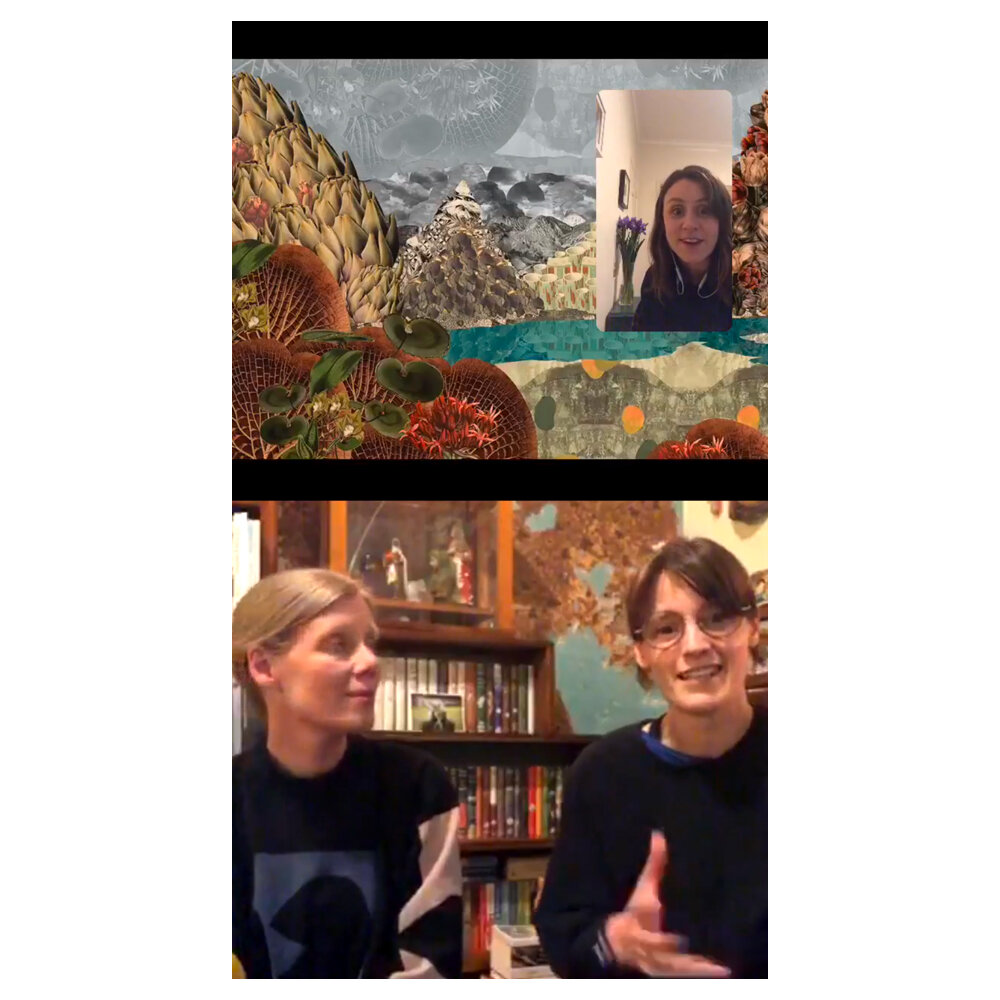

2/ Gracia Haby & Louise Jennison in conversation with Jess Cole, Assistant Curator, Prints and Drawings, at NGV

October, 2020

On the @NGVmelbourne IGTV channel

This ‘live’ conversation on a Wednesday eve, at 7pm on the 7th of October, 2020, was in the room in which you would normally find us working at that time of night. It is the room in which we made the collages on cabinet cards housed within The Company You Keep, on two drawing boards on the floor, adding a Nicobar pigeon (Caloenas nicobarica) to accompany someone’s Grandma Ferry. It is the room in which our twenty-plus-year collaborative work has been dreamt up and completed. Our home is our studio. It is where we are, so it is where we make; where our heads and heart and animal friends reside is all the space we need.

Live in-studio artist visit: Gracia & Louise

WATCH

Melbourne-based collaborative duo Gracia Haby and Louise Jennison have been working together for 20 years using paper as their primary medium. Join them as they talk with NGV Assistant Curator of Prints and Drawings, Jess Cole to discuss their practice and work in the NGV Collection.

National Gallery of Victoria

﹏

RELATED LINKS,

REEL

LIVE IN-STUDIO ARTIST VISIT (NGV)

THANK-YOU

LOOKING FORWARD

“I was curious and amused — a night parrot, a marmoset and a bilby each side-eyed me back from three different zines”

Zoë Sadokierski

2020

For EXTRA!EXTRA!

The Rizzeria

In Kyoto, I came across a small shop that sold only fruit. Each piece was displayed individually, cradled in a filigree-fine foam mesh. I selected a single orange. At the counter, an immaculately groomed sales assistant swaddled the orange in layers of translucent rice paper and carefully nestled it in a box; a clever piece of paper engineering that folded closed without need for string or tape.

An orange doesn’t need packaging; its natural wrapping looks and smells appealing and protects the edible flesh. But that Japanese orange was an event. Opening the box and unwrapping the delicate, textured layers fostered a Christmas-like sense of anticipation. The Japanese are masters of turning simple activities like making a cup of tea or giving someone a piece of fruit into a sensual experience.

Food shopping at home, I often chuck a couple of oranges into a plastic bag*, yanked from a roll like toilet paper and opened via frustrated rubbing between fingers. This experience does not inspire me to reflect on the beauty of a single orange. Although the packaging was superfluous, the ceremonious Japanese orange gave me pause to appreciate the perfection of the fruit.

+

If the orange is a perfect fruit, the codex book is a perfect reading technology. By codex, I mean a block of pages, bound along one edge, protected by a cover. A book, as we know it. A format that’s remained largely unchanged for centuries. It’s portable, doesn’t require electricity or software updates, and simple to use: turn the pages to reveal the story.

A publisher once told me that a good book covered in brown paper would still sell. He meant that a good book doesn’t need fancy packaging (design) — it’s already a perfect object. To him, book covers and design elements such as typesetting are superfluous.

He may be correct. The arrival of ebooks seem to support his argument. When we purchase a book on an electronic device we’re not buying a book, but a piece of code, a digital file that can be uploaded onto whatever device we choose to read it on: tablet, smart phone, desktop computer. Beyond a thumbnail ‘book cover’, an ebook has no tangible presence until it appears on screen to be read. It disappears from view when the device is turned off, or app closed.

With e-publishing, book design becomes largely irrelevant. Of course there is still design involved in the process; someone (or probably a team) designed the template/interface that an ebook flows into, and in the case of a reading tablet, selected the typefaces readers may choose to display their book. Yet individual books are just floating code, waiting for a container. There is little unique design in an ebook. The brown-paper publisher was correct, a good book will sell even if packed in the digital equivalent of brown paper: a generic template.

But what we are discussing here is book sales, which is different to the reading experience. Publishing is a commercial enterprise. For a single book to travel from the imagination of the writer to the hands of a reader, it must pass through countless other individuals, each (in theory) paid for their expertise, labour, resources. Conversations about the future of book publishing mostly focus on sales statistics: how print sales compare with e- and audio book sales, how the indies are performing against the conglomerates, how Amazon is ravaging bricks and mortar shops. Yet to understand the future of books another question is also crucial: how much do people still enjoy reading books?

There will be no future market for books if people lose interest in longform reading. My mobile phone is a portal to more reading material than I could possibly read in a lifetime. In ten lifetimes. I have a terrible habit of emailing/bookmarking/wish-listing books and articles for some future less-busy moment, despite knowing there will never be a less-busy moment because I have stockpiled more than is possible to read in a lifetime. I discovered, via a meme on some platform or other, that the Japanese word for allowing reading material to stack up is tsundoku. My tsundoku tower fills me with guilt and fatigue, not anticipation or a desire to read.

Back to the ceremonial orange. One of the things lost with digital reading devices is a sense of distinction. With a tablet or smartphone, I’m not carrying around one orange, I’ve got the whole tray. If I’m online I have access to the orchid. But there are apples, as well. I have a list of television and podcast series I’m desperate to consume. Social media generates unthinkable quantities of reading material every nanosecond. My devices constantly demand I keep up, interact, share, contribute. There is no time for ceremony when everything is immediately accessible and seemingly urgent. How do I keep my eyes, and more importantly focus, on the page (or screen) long enough to enjoy the experience of sustained reading?

Bibliophiles understand that there is more to a book than quickly accessing the story or information it contains. This is, in part, where design does more than simple packaging for consumption. A thoughtfully designed book captures our attention, in a focused, embodied way. It turns a text into a reading experience. An encounter with a narrative that we must make time and space for.

Here are some of the things I love about the materiality of a printed book. I approach it from a distance — it doesn’t suddenly appear in front of me. Coming at a book on a shelf or table, I have time to size it up, get a sense of it as a unique object in the world. I bond with it: run my hand across an embossed title on the cover, rub creamy paper stock between my index finger and thumb, gauge its heft in my hands. I open it and shuffle my thumbs around until my hands settle comfortably. I love the singleness of purpose. A book doesn’t network to distractions. There’s a clear beginning, middle and end. A book exists to tell me a story. Just one story. Of course I can interpret that story many different ways, in different moods or at different points in my life I may return to that one story and find it entirely new, but the words — and images — on the page remain unchanged. There is comfort in this. Knowing that when I return to this object it will be exactly as it was. If there is a change, it comes from me; a book is a mirror in which I can reflect on myself.

I’m not arguing that all books should be printed. I think some books are better as inexpensive ephemeral files that can be read with abandon, then abandoned. But that should be an option, not the rule.

In the conversation about the future of books and publishing, if we only look at sales figures, we risk placing too much attention on production and distribution profit margins and not enough on the experience of reading. A future for books is determined by a ceremonial celebration of reading, and ceremony requires objects to have and to hold, to value as unique things in the world.

+

In mid-March 2020, my partner was in Melbourne for work and obligingly collected a package of artist books and zines from Gracia Louise — a bookmaking duo I’ve admired for years via social media but never actually met — at the NGV’s Art Book Fair. I’d purchased the collection in the #AuthorsForFireys Twitter auction, supporting firefighters who battled the nightmare bushfires in late 2019. By the time he arrived back in Sydney with the books, the world was collapsing into lockdown to prevent the spread of Covid-19 and I was collapsing into a void of logistical and emotional chaos, figuring out how to perform my roles as design educator and researcher, mother and partner, during a pandemic. The package of books sat unopened on my bookshelf for almost 2 months. I looked at the mystery collection often, carefully stacked between the printer (working) and typewriter (decorative). My furtive glances were not tsundoku malaise. I was curious and amused — a night parrot, a marmoset and a bilby each side-eyed me back from three different zines, and two booklets with brown paper covers left me with no hints to the content within (turns out they were shelved upside down, the covers feature a lynx and tiger and — spoiler alert — they contain sublime sketches from natural history museums around the world). I could acknowledge their presence but not yet open them because I was galactically exhausted. As the Zoom/Teams/Slack commitments yawned into an amorphous suckhole of time and energy, and what little zest remaining was needed to field preschooler questions such as “when will humans die?” and “after I die will I be born again?” and “what are we doing today?”. So the little stack of books lay waiting, until I could muster the attention I knew they deserved.

This is not the first time I’ve deliberately drawn out the opening of a book. My copy of Where You Are, a box of ‘literary maps’ from UK experimental publisher Visual Editions, sat on the shelf at work – directly behind my monitor, visible in my peripheral vision — for an entire year. I received my copy via a friend who’d bulk ordered for a group of us (international shipping to the nether-regions of the globe is often more costly than the unit itself) and for various reasons it took so long for the book-box to get to me that I’d forgotten I’d ordered it. When it landed in my hands, I was hanging two exhibitions in the middle of a teaching semester — so also galactically exhausted, but that time self-induced. It became a kind of psychological dangling carrot: when you’ve learnt to be less berserkly busy, you’re permitted to open this wonderful thing that you will love. Twelve months later, I rewarded myself for being only stupidly, rather than berserkly, busy. Almost eight years later, I still love that box-book, but each time I reach for it (mostly as a teaching resource now) I am reminded of my berserk 2012 self.

Back to the Gracia Louise collection. Seven weeks into New Normal I broke. Upon finishing a five-hour Zoom tutorial, I found myself still sitting in front of my computer half an hour later, hunched over my mobile phone, shopping for clothes I had no intention of buying via an Instagram ad. WTF. My 2020 berserk is exponentially worse — mentally, emotionally, environmentally — than my 2012 berserk. I put my phone down, walked to the park across the road and had a brief cry under a tree. Back at home, I went to the toilet then ate something — basic self care that should have happened during the five-hour Zoom session and not an hour or so after it. I brought the books out to the kitchen bench (quick wipe to ensure a clean surface), the warmest and best lit space in the house. I lined the eight books up in a row from largest to smallest. Then I clustered them by binding – one H-fold zine, five thermal tape bound booklets, one perfect (glue) bound (uncoated board with red foil) and one print wrapped in delicate tissue paper which slips into the perfect bound board book. So seven books, with one insert. That day, that was enough. I stacked and returned them to their shelf.

A week later, here I am. The seven books are before me, waiting patiently as I finish writing this article. Shortly, I will dock the laptop and all other devices, pour a gin and tonic and settle in with the collection for the rest of the night. This is the ceremony I need. I won’t read them all, cover to cover, tonight. I may flick through them all, and then decide: enough, until next time. I may closely read one, two, or even binge three. It all depends on my intellectual and emotional capacity to give these books — and their authors and all the hands they passed through on their way from Gracia Louise to me — the focus and keen attention to detail that they deserve. I have a box waiting for them. It’s matte black, just large enough, and closes with a satisfying invisible-magnet click. These books don’t need a box; I can stack them as they have been shelved for the past two months in my care. But this quietly elegant box will protect them from dust and begin the ceremony of slow reveal, each time I focus my attention on this collection in the days, months and years to come.

* This first part of this essay was originally a talk at the Sydney Writers’ Festival in 2015, written before using plastic bags in supermarkets was considered a minor felony. I now just chuck the oranges into my basket, unless I’m at Harris Farm, then I chuck the imperfect pick into the green bag. I’m telling you this so you judge me less harshly as a human for spending seven hours in front of screens without going to the toilet.

Zoë Sadokierski is an award-winning book designer, writer and senior lecturer at the UTS School of Design, where she is part of Spec Studio, a collective of design researchers exploring narrative approaches to ecological communication. She is former president and a founding member of the Australian Book Designers Association. In 2015 Zoë established Page Screen Books, an independent publisher of artist’s books and visual essays.