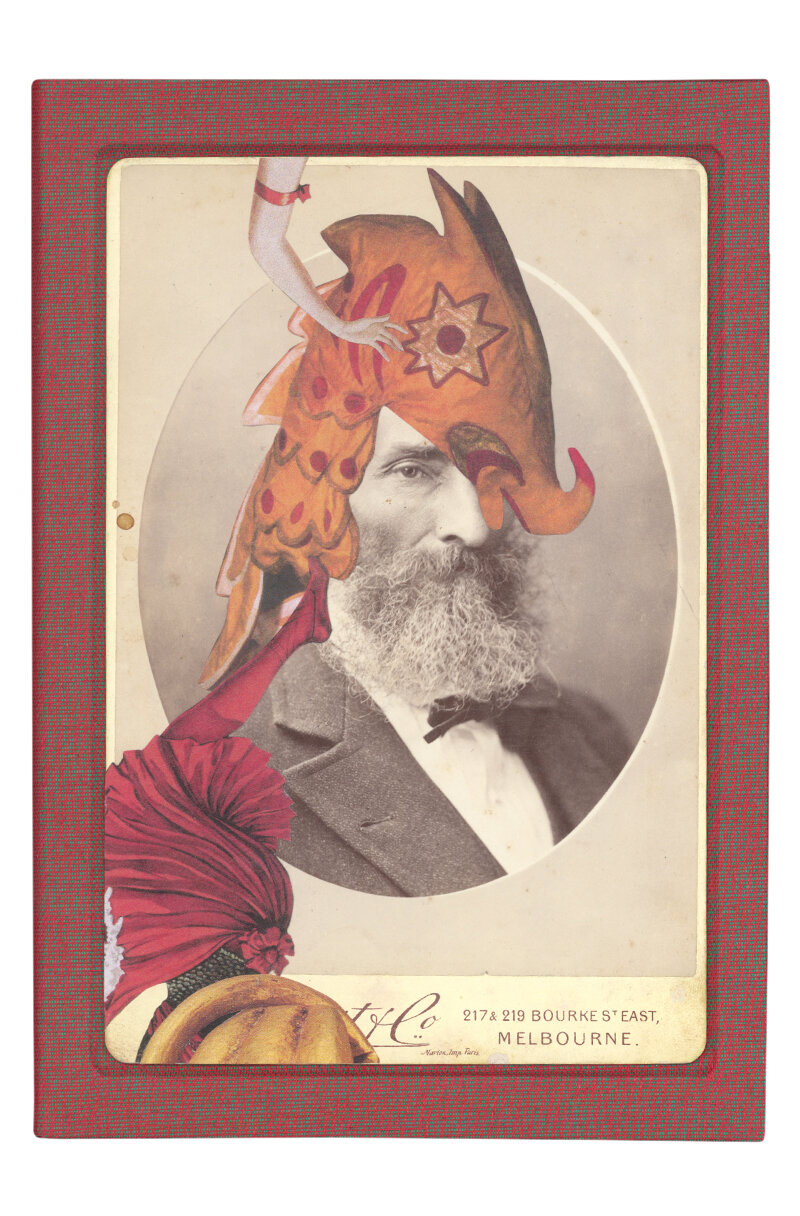

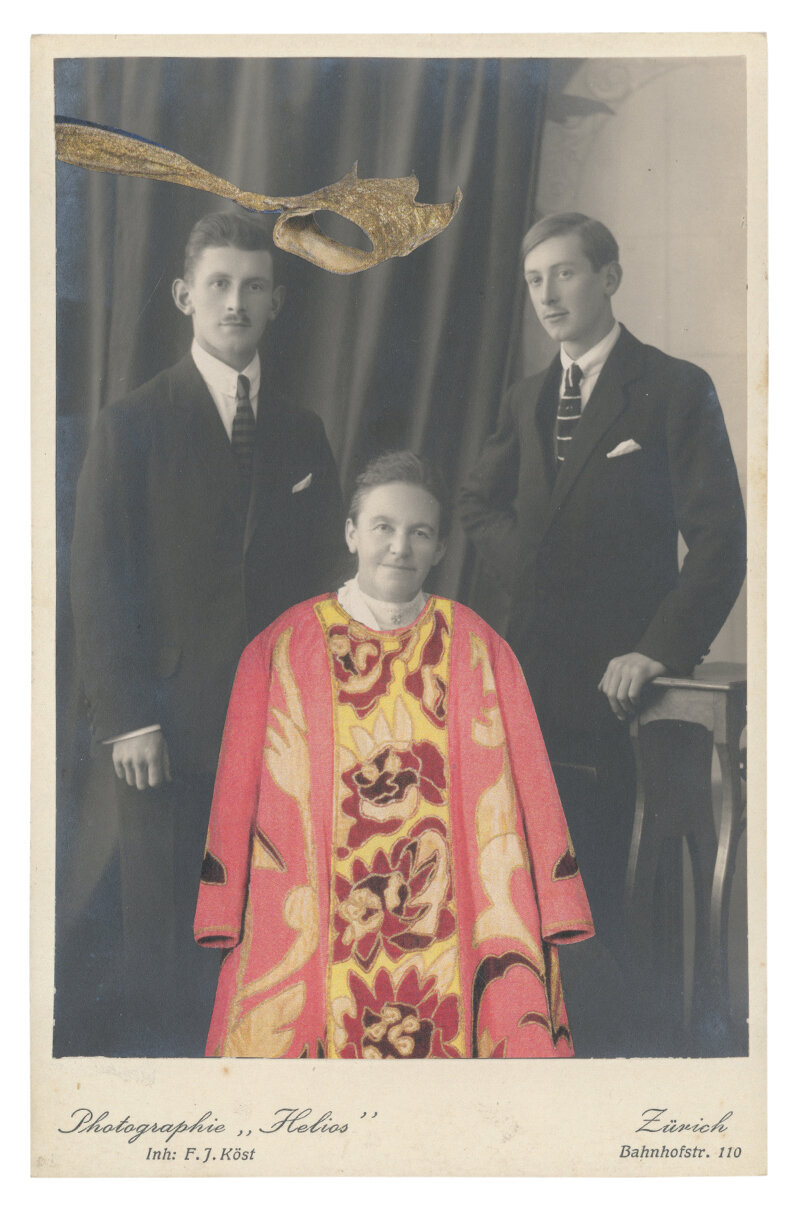

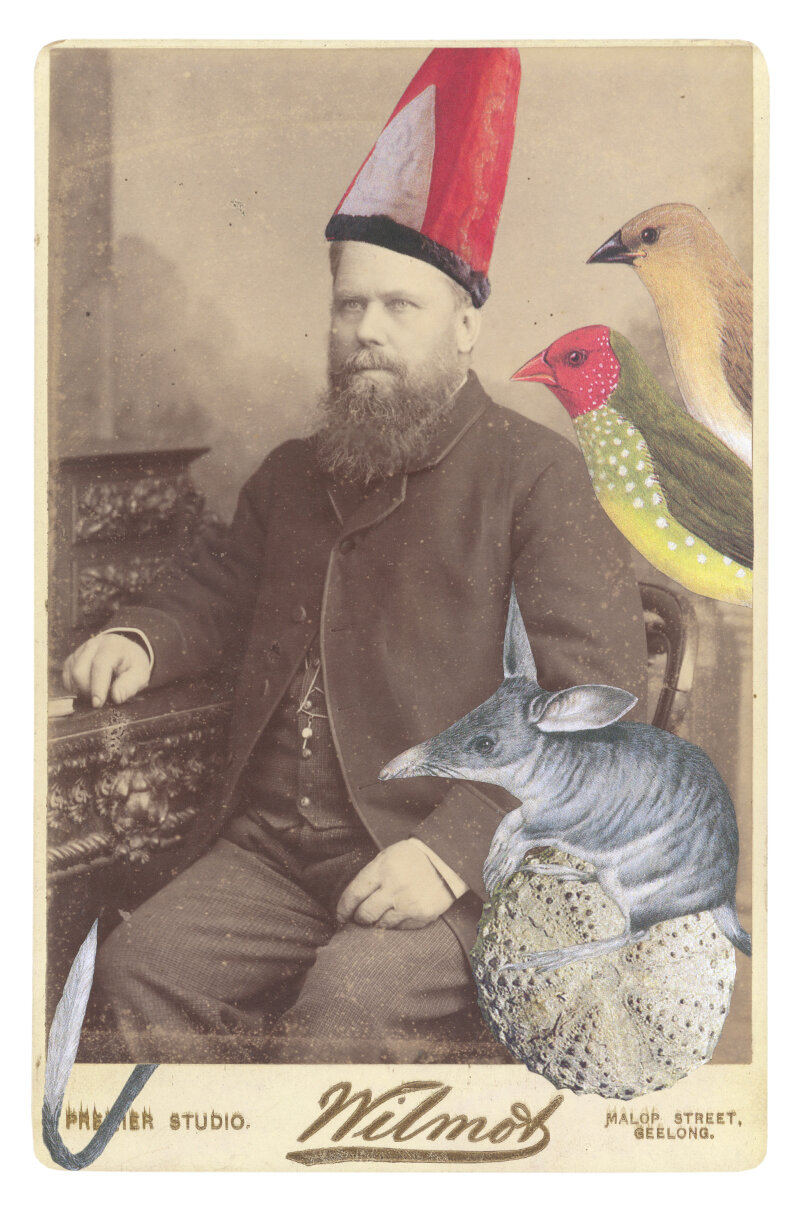

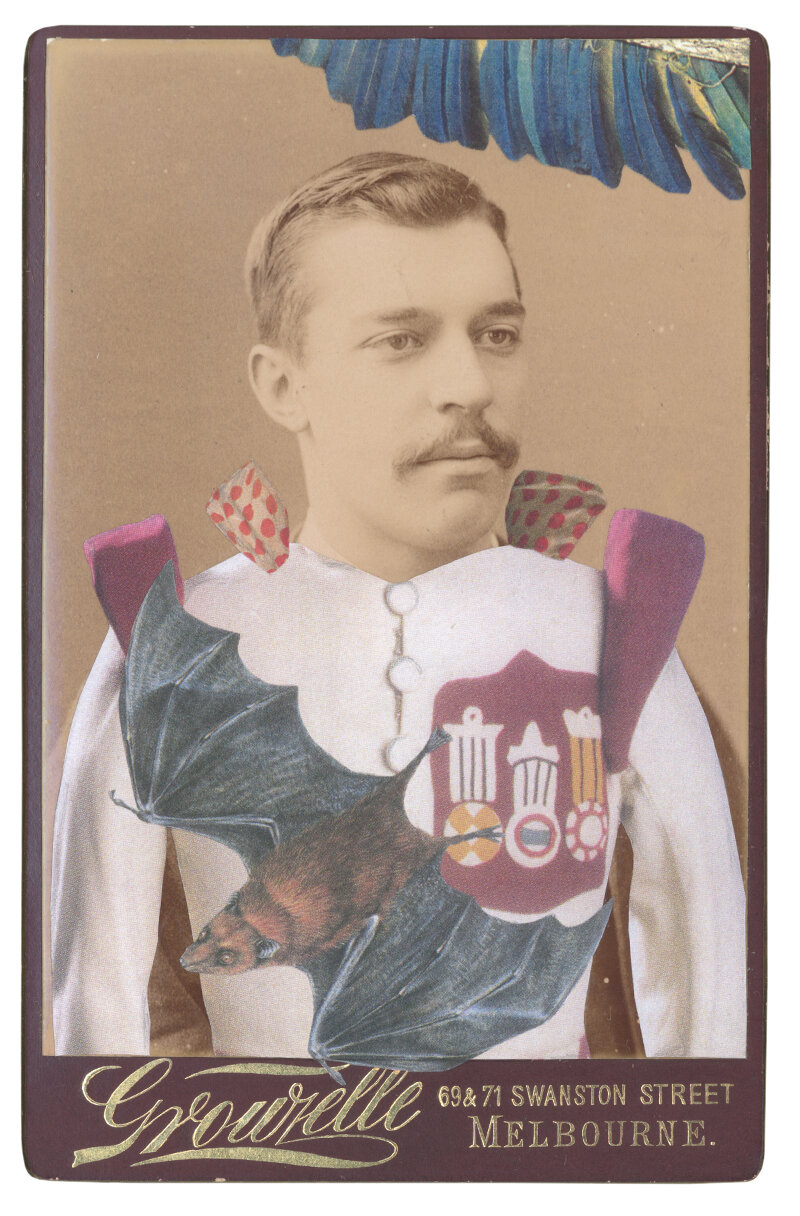

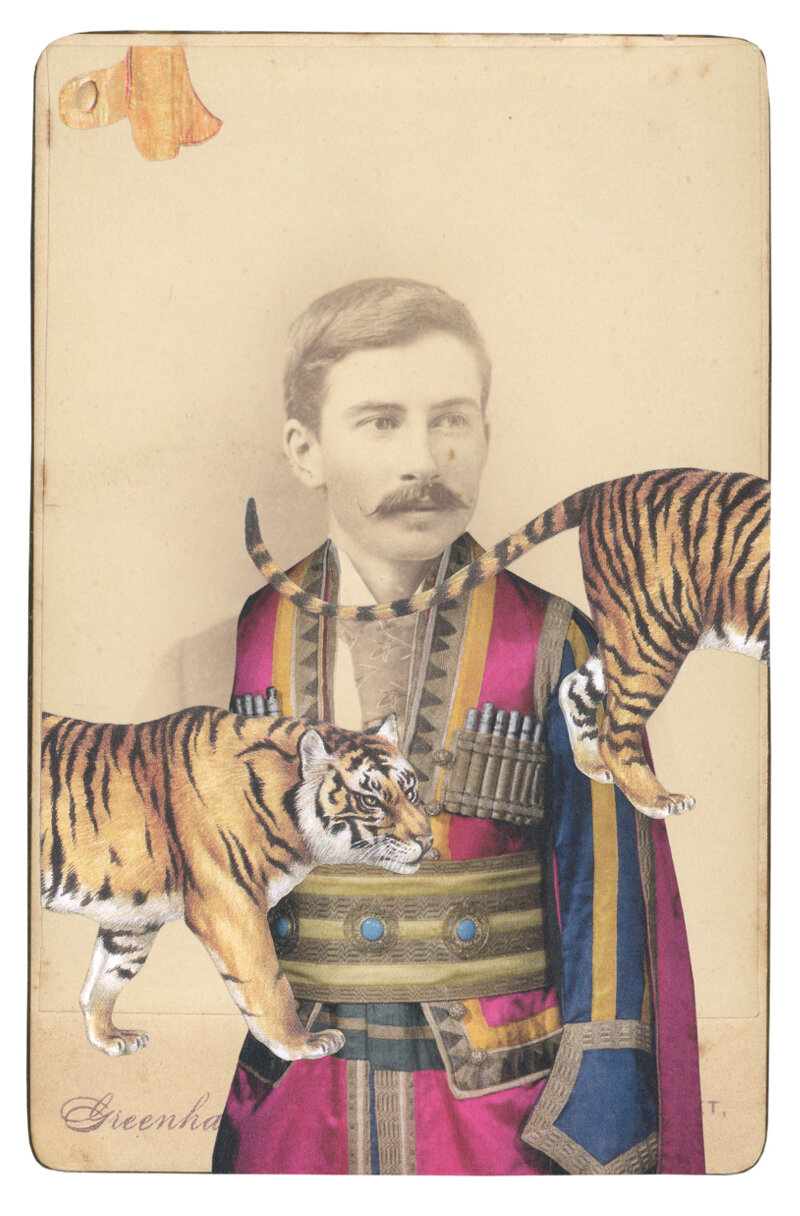

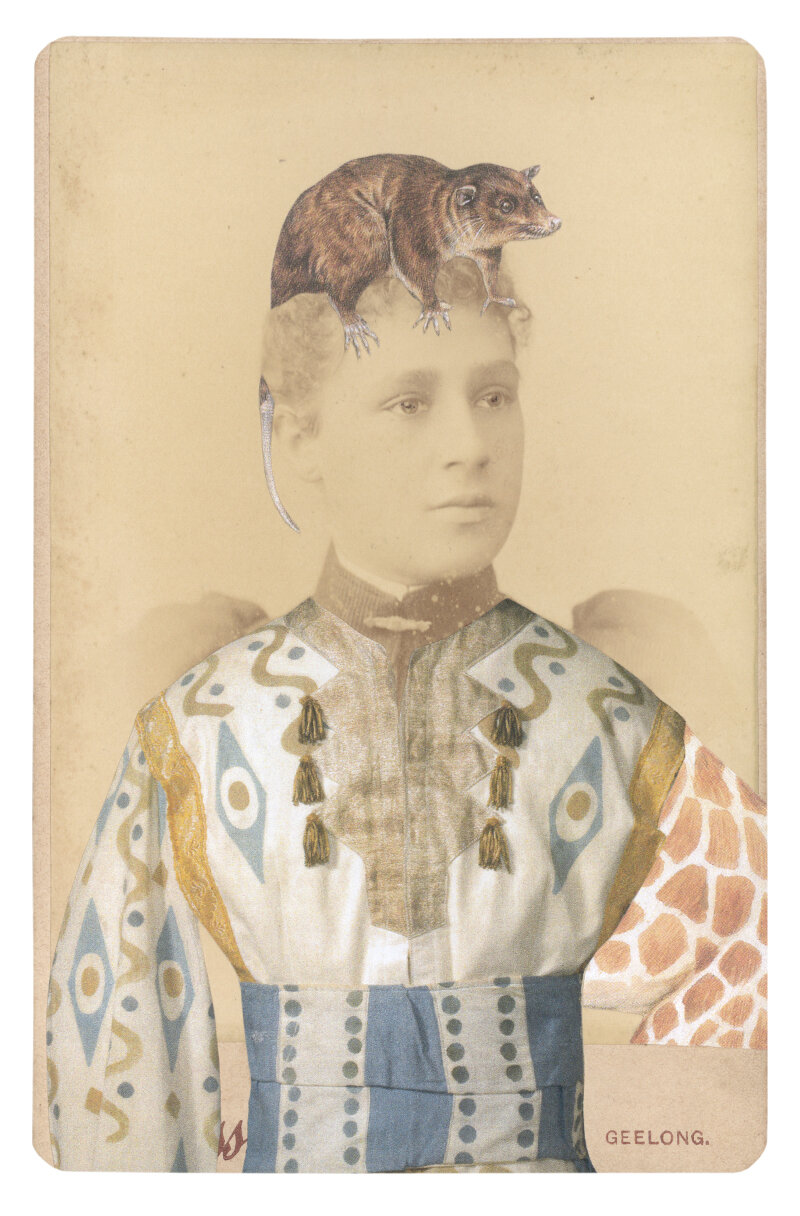

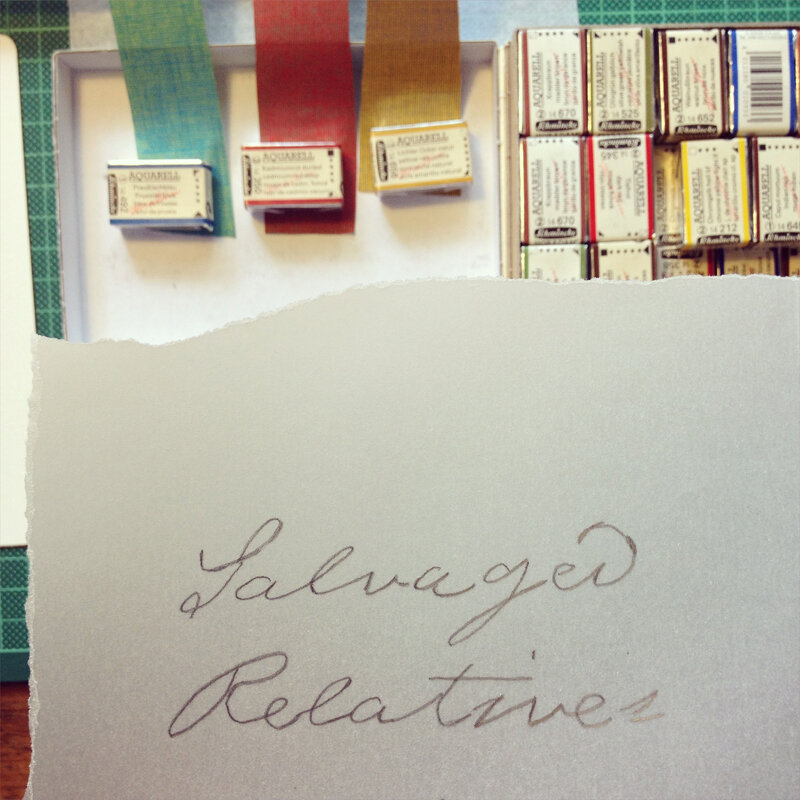

SALVAGED RELATIVES, 2014–2015

Gracia Haby & Louise Jennison

Salvaged Relatives, edition I

2014–2015

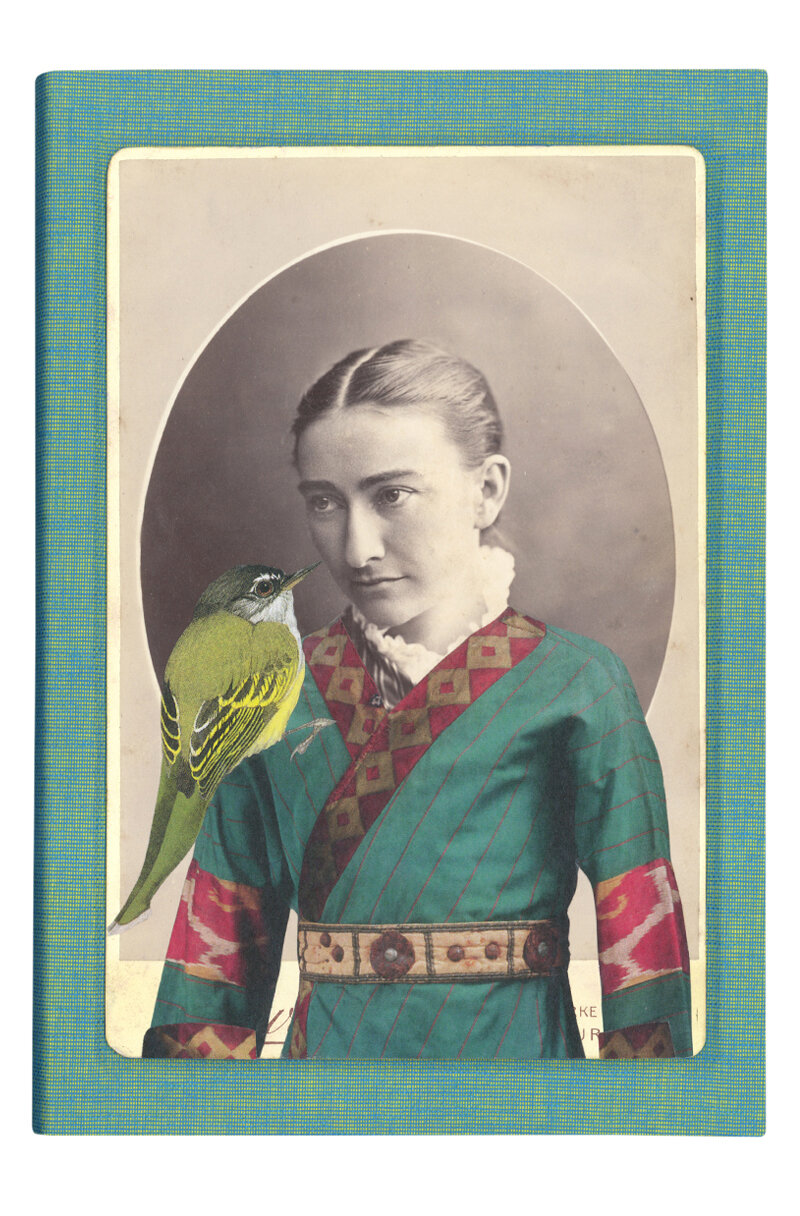

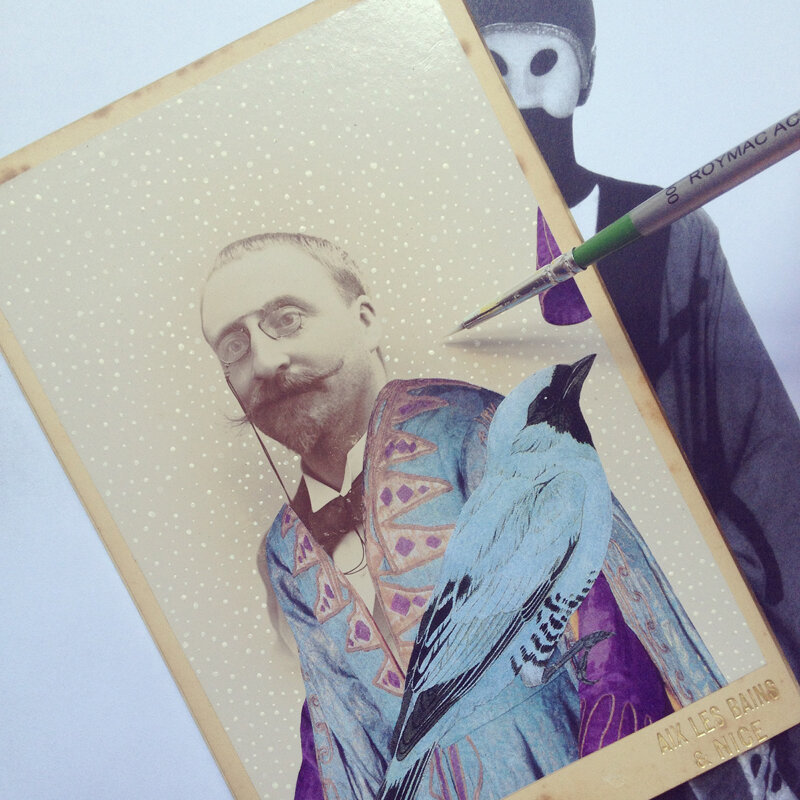

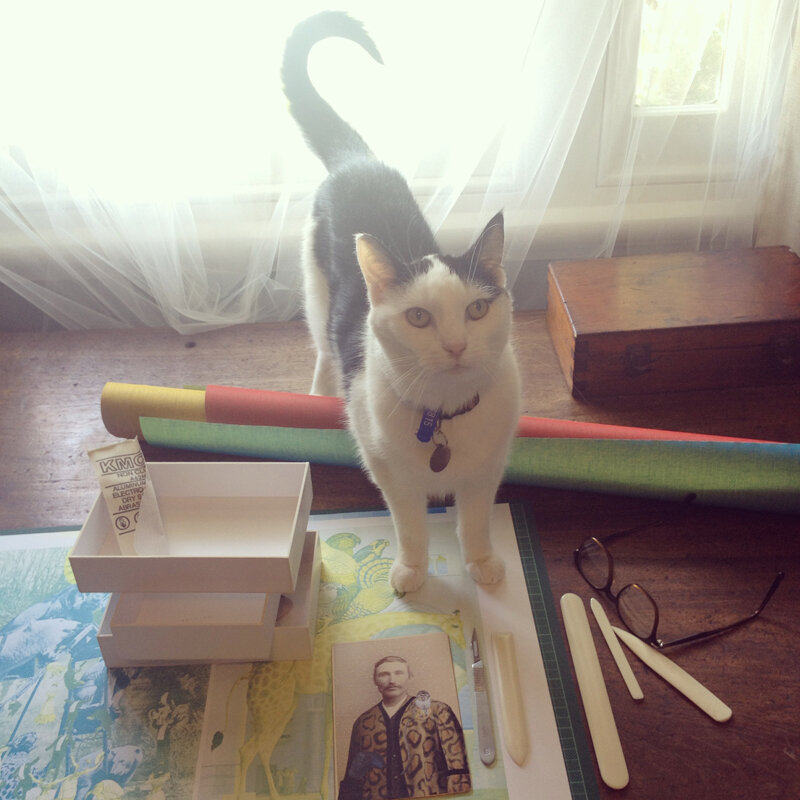

Artists’ book, unique state, featuring 21 individual collages on cabinet cards with pencil and paint additions (by Gracia Haby)

Housed in a three-colour cloth Solander box (bound by Louise Jennison) with inlaid collage, In the borrowed headdress of a seahorse from Sadko (c. 1916)

Salvaged Relatives, edition I, is in the collection of the State Library of New South Wales.

Sporting costumes from the Ballet Russes, including Nijinsky’s Blue God tunic modified and a Eunuch’s embroidered silk and velvet sensation from Shéhérazade, all three editions were launched as part of a One Night Only viewing on Wednesday the 11th of February, 2015, at Milly Sleeping in Carlton.

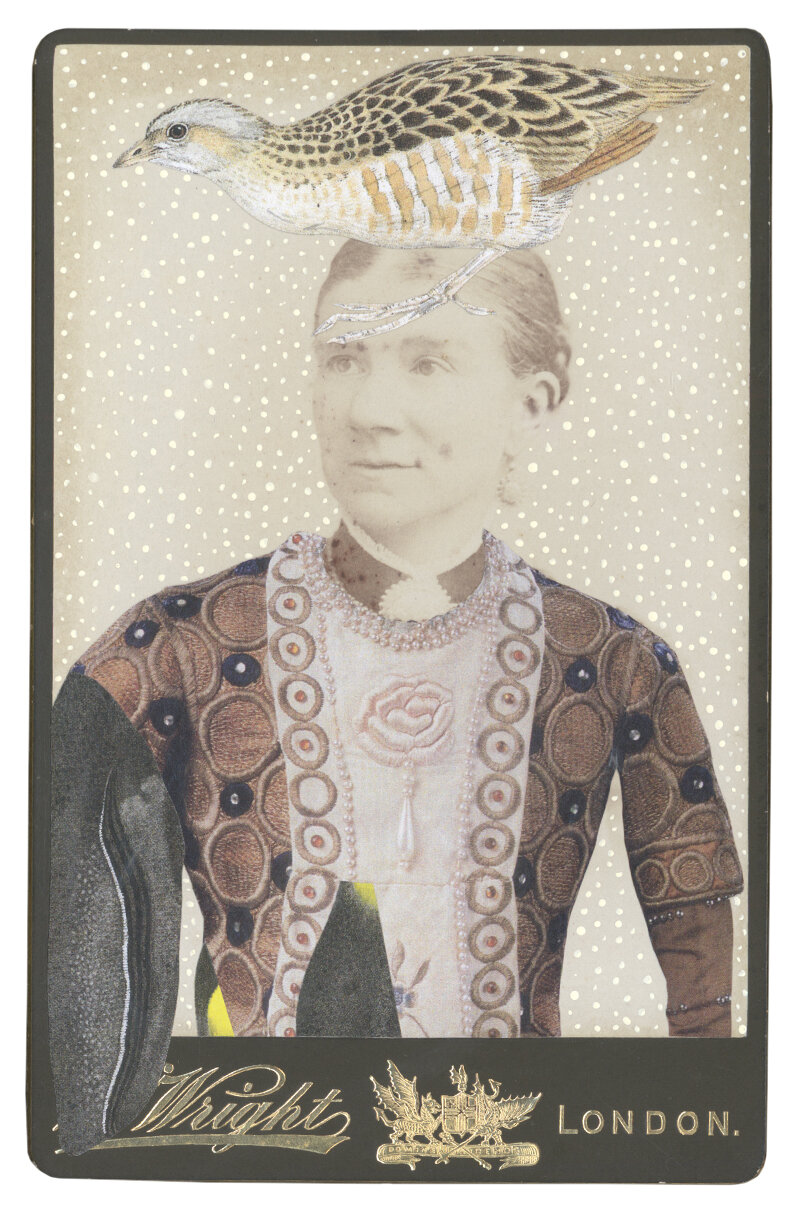

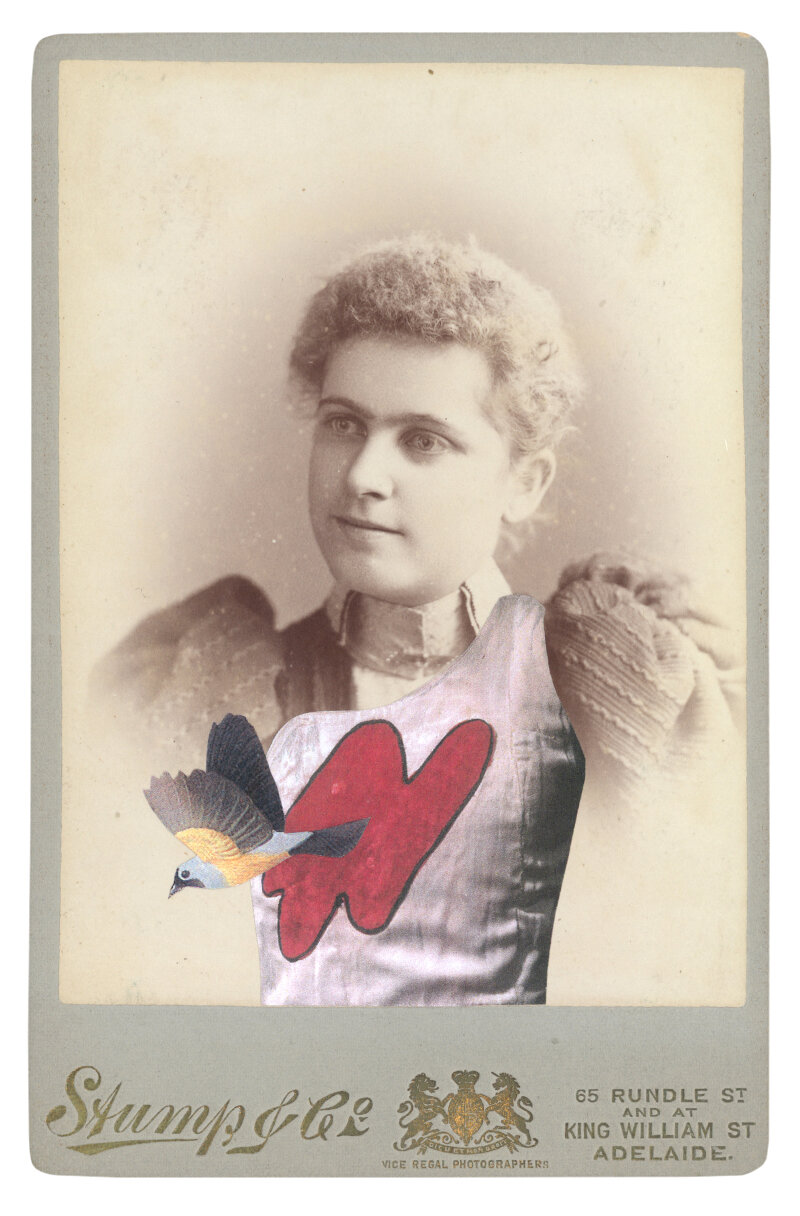

1. In the borrowed costume for a lady-in-waiting, c. 1921, designed by Léon Bakst, with a Piapiac (Ptilostomus afer)

2. In the borrowed costume for a squid from Sadko, designed by Natalia Goncharova, c. 1916

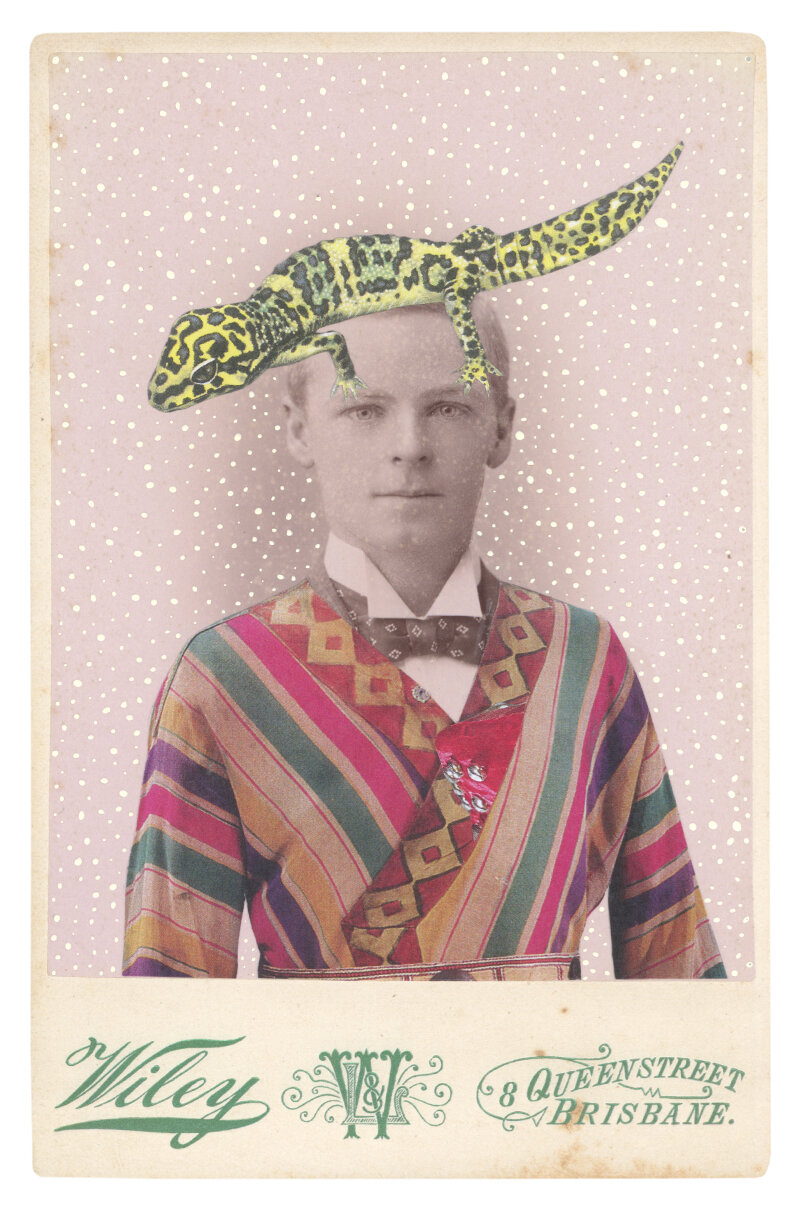

3. In the headdress of Shah Shahriar from Shéhérazade, 1910–30s, with a Jungle runner (Ameiva ameiva)

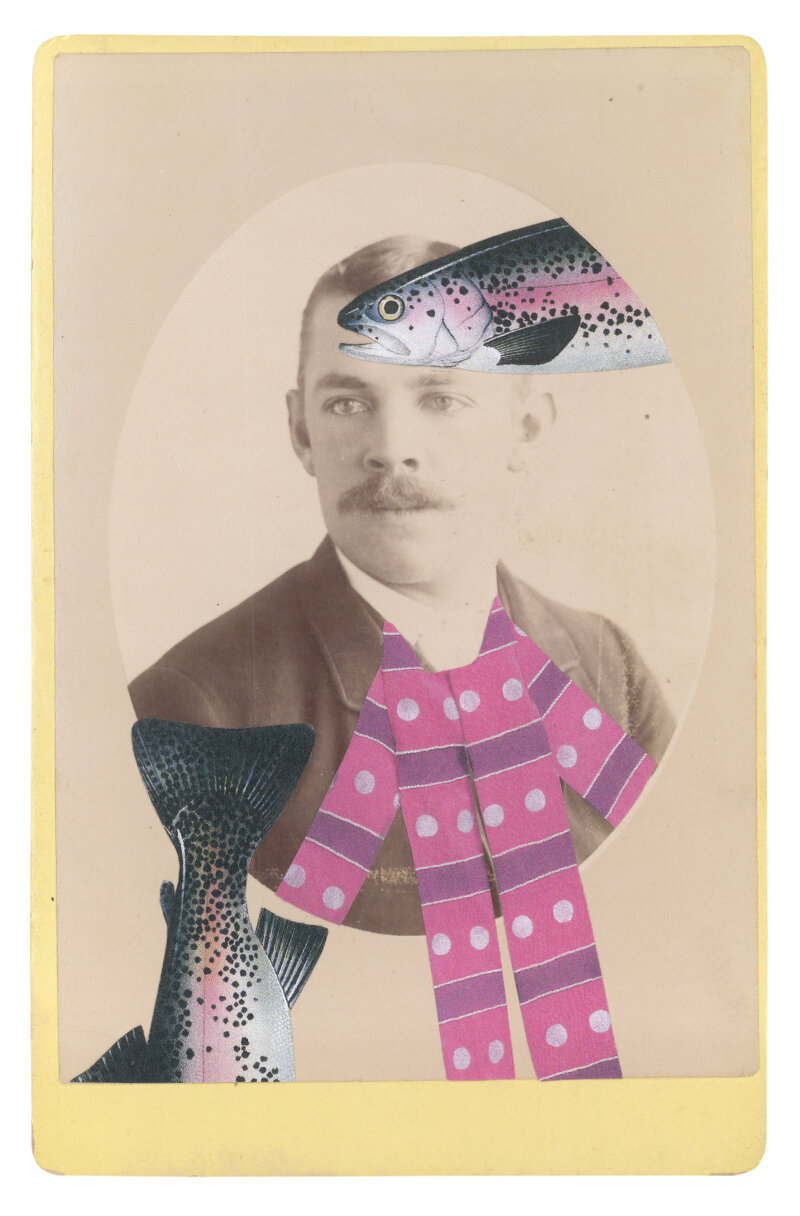

4. Fashioned as a necktie, a modified costume for a slave or dancing girl from Cleopatra, 1909, with a Rainbow trout (Salmo gairdneri)

5. In the borrowed costume for an Ivan, c. 1922, designed by Natalia Goncharova, from Aurora’s Wedding, with a Golden cat (Felis aurata)

6. In the borrowed costume for Queen Thamar, c. 1912, with a House mouse (Mus musculus) and a Marsupial mole (Notoryctes typhlops) tucked under the arm

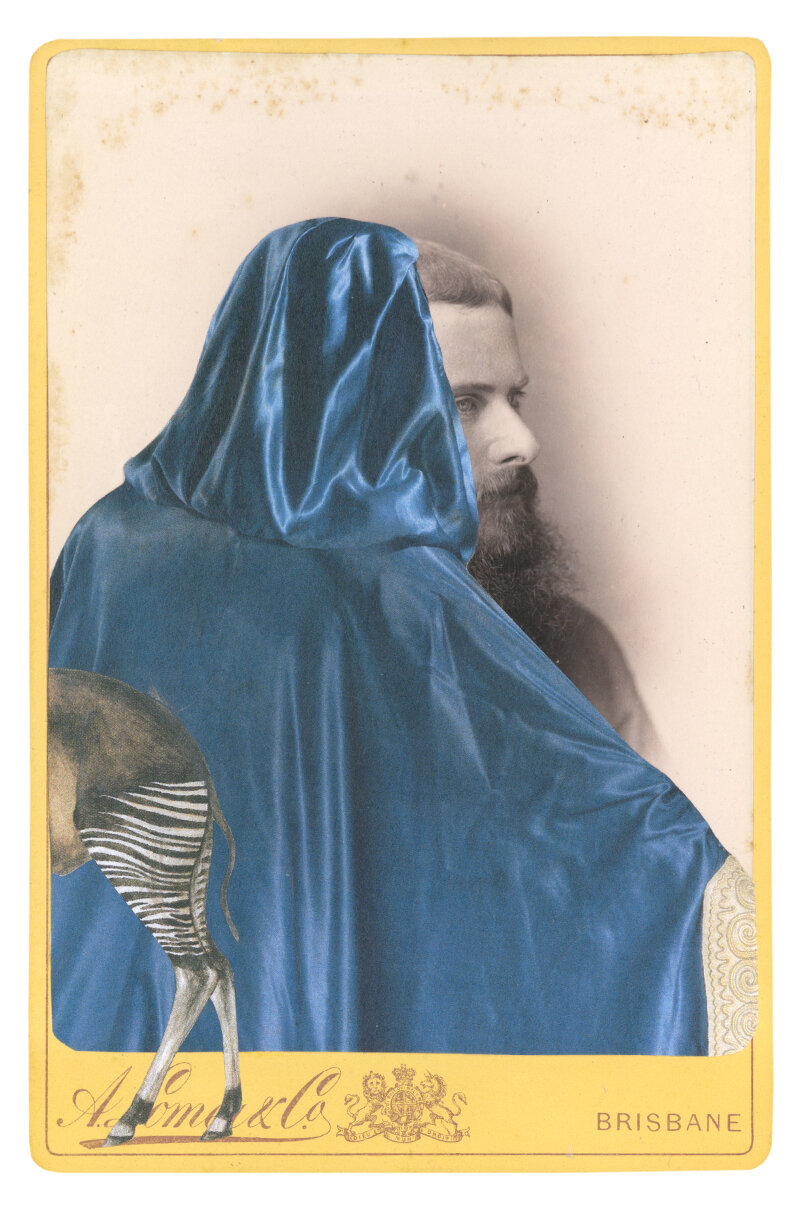

7. In the headdress of a Maiden from The Rite of Spring, 1913, with an Okapi (Okapia johnstoni)

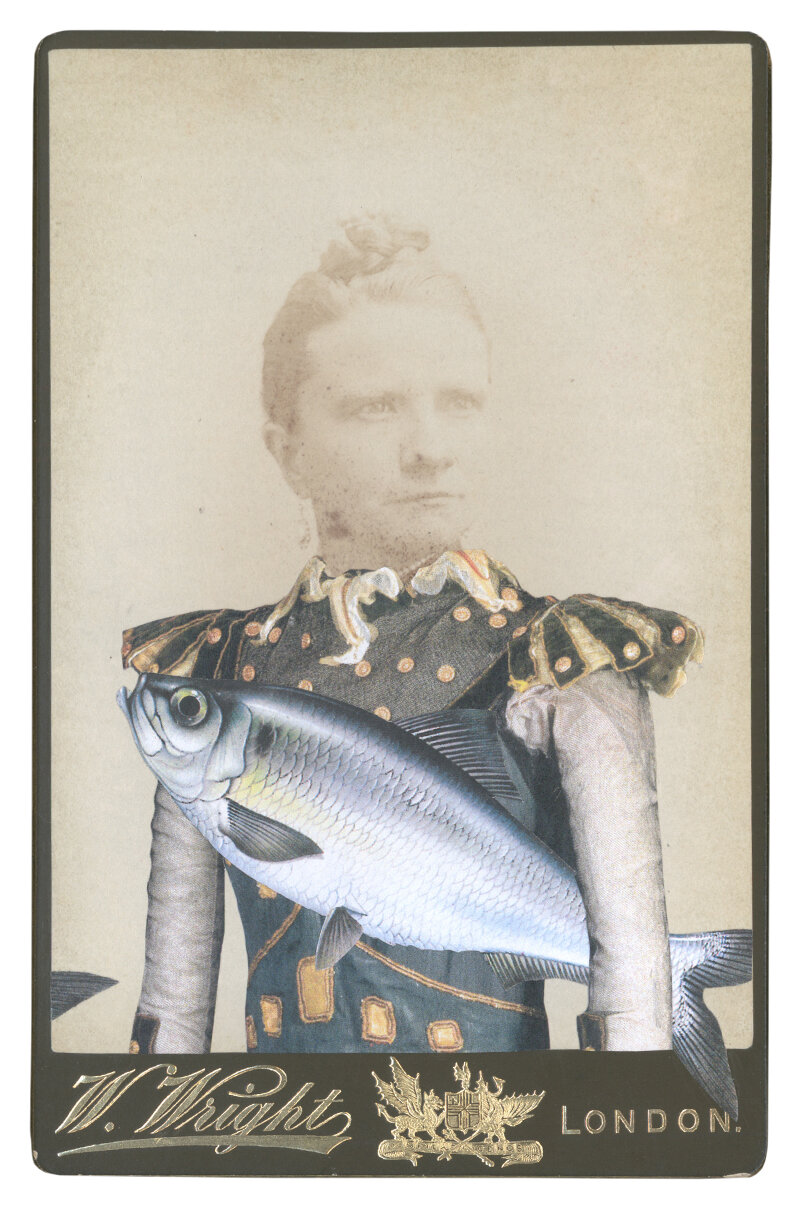

8. In the borrowed costume for a Court Lady in Francesca da Rimini, c. 1937, with an Alewife (Alosa pseudoharengus)

9. In the borrowed costume for a Coronation Scene from Boris Godunov for Diaghilev’s Saison Russes, c. 1908, with a three-toed sloth (Bradypus variegatus)

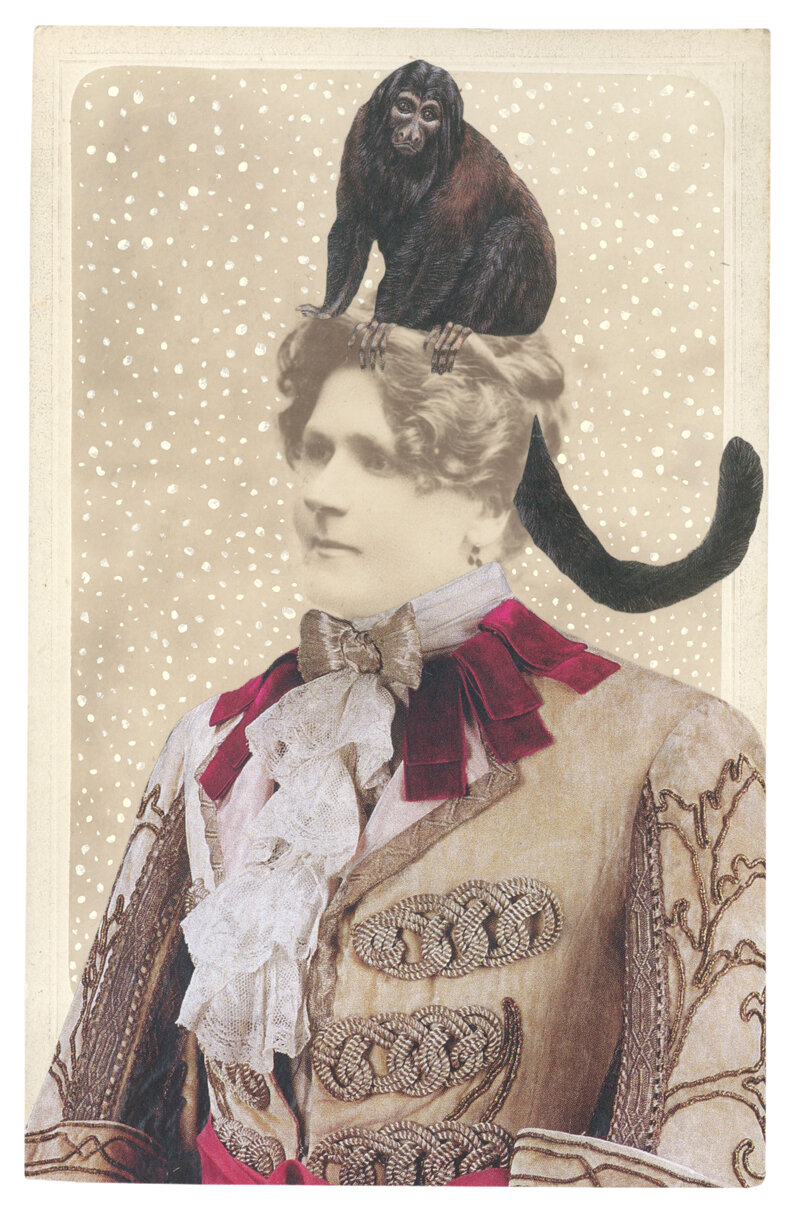

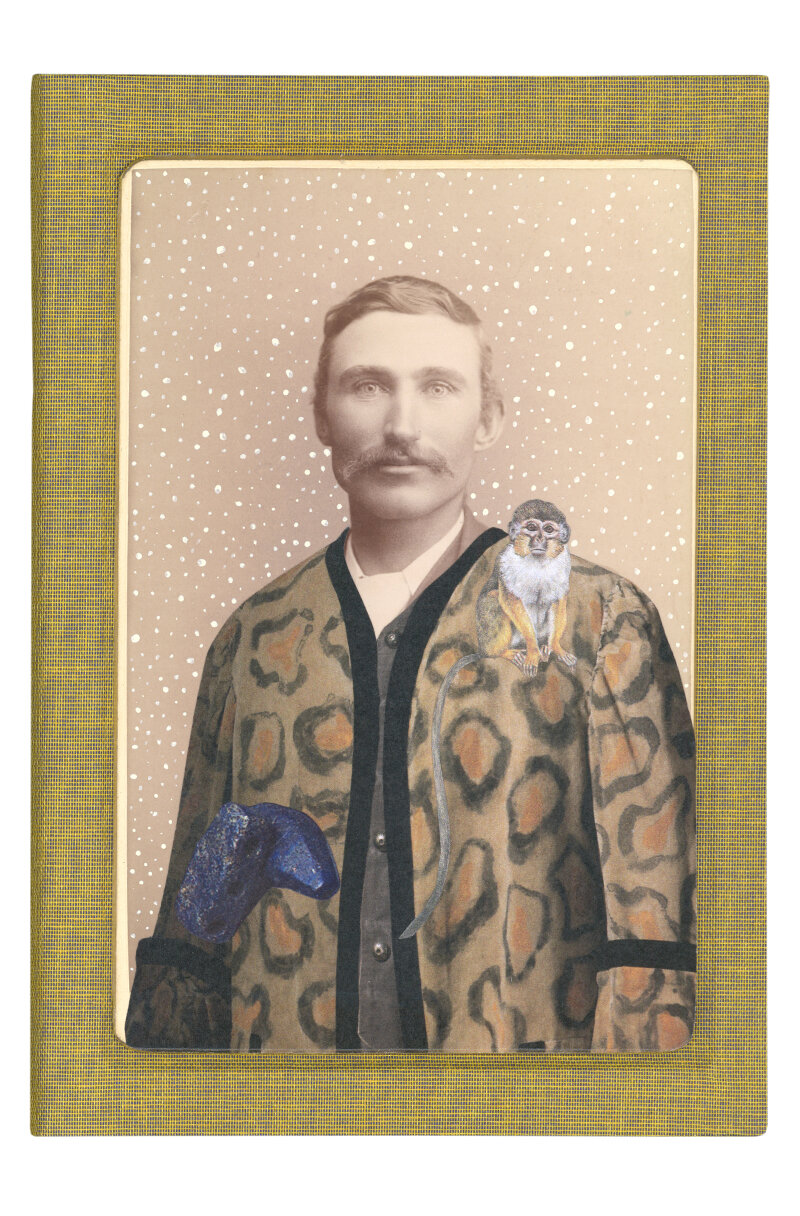

10. In the borrowed costume of Prince Charming from The Sleeping Princess, c. 1921, with a Black-bearded saki (Chiropotes satanas)

11. In the borrowed costume for a Prince, with ‘essence d’orient pearls’ from Sadko, c. 1916, with a Red fish (Sebastes marinus)

12. In the borrowed costume worn by Doris Faithful as the Sea Princess from Sadko, after Natalia Goncharova, 1916

13. In the borrowed costume for a slave or dancing girl, designed by Sonia Delaunay, 1918, with a Chaffinch (Fringilla coelebes)

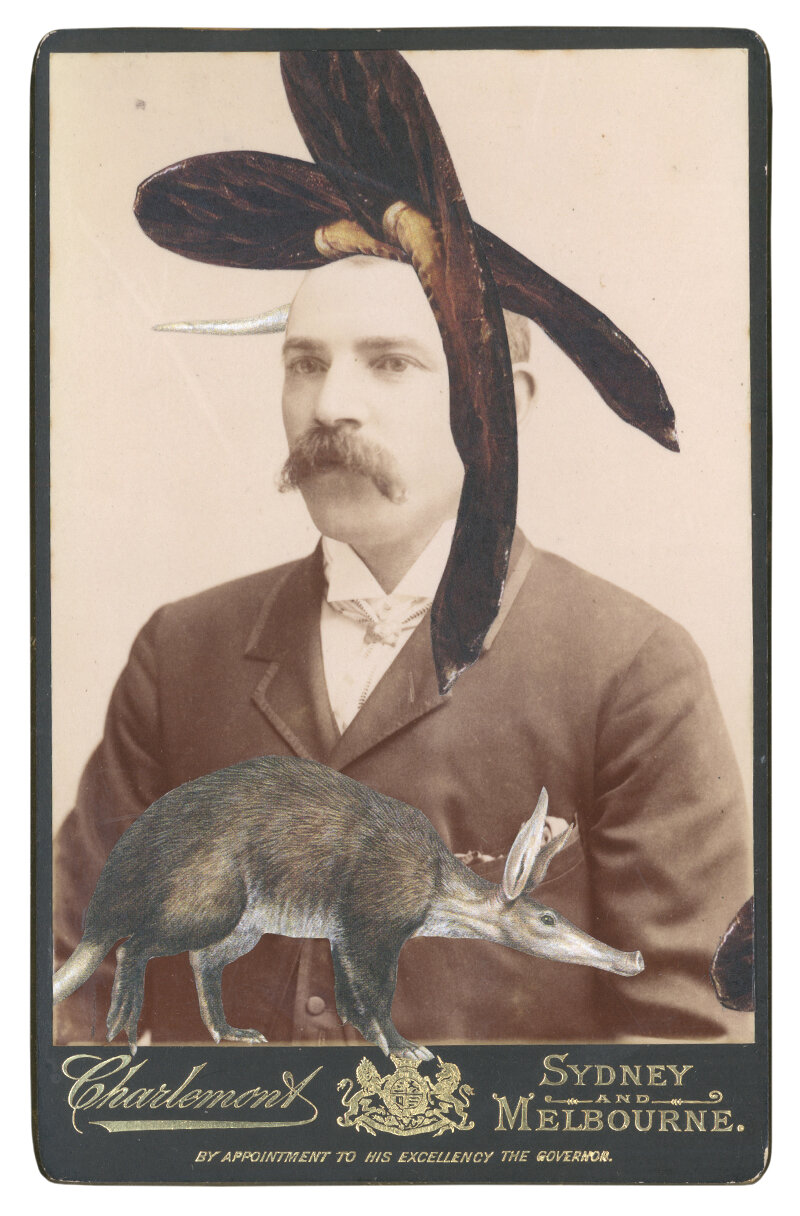

14. In the modified headdress for the Mandarin from The song of the nightingale, after Henri Matisse, 1920, with an aardvark (Orycteropus afer)

15. In the borrowed costume for a Polovtsian Warrior from Prince Igor, c. 1909, with a Leopard gecko (Eublepharis macularius)

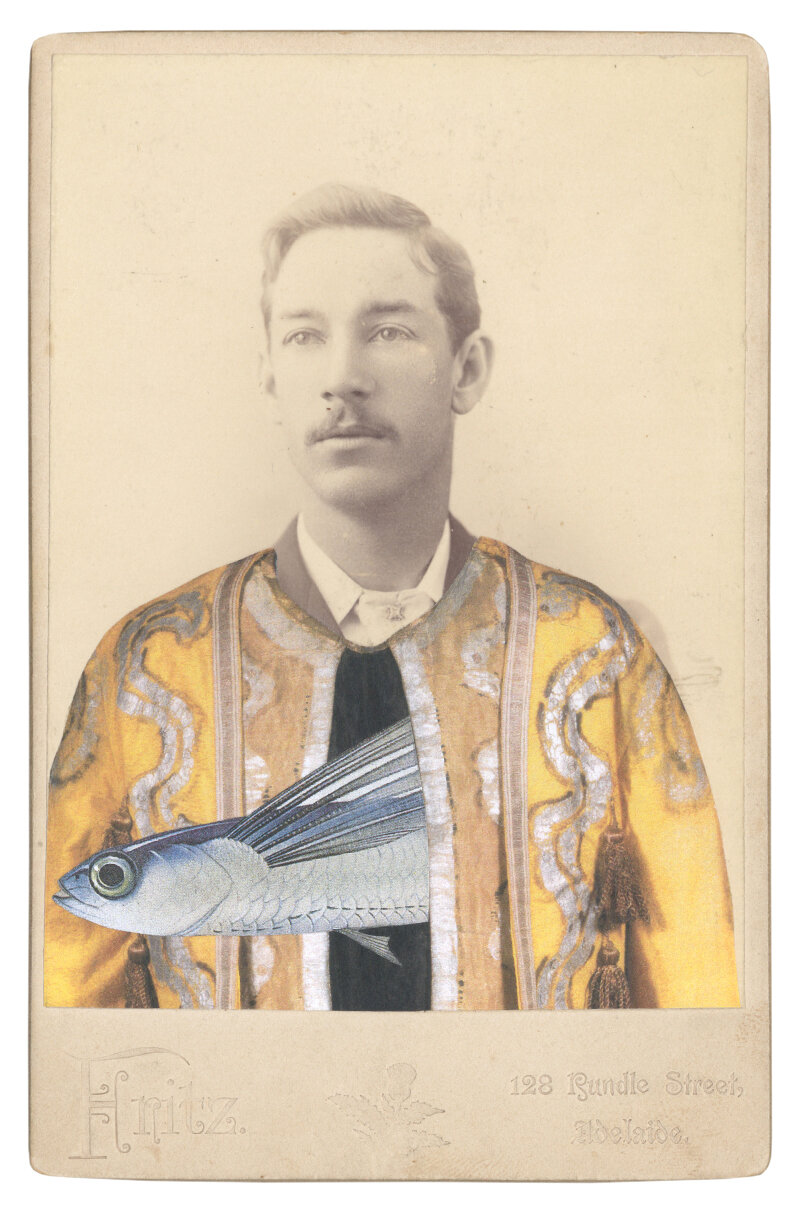

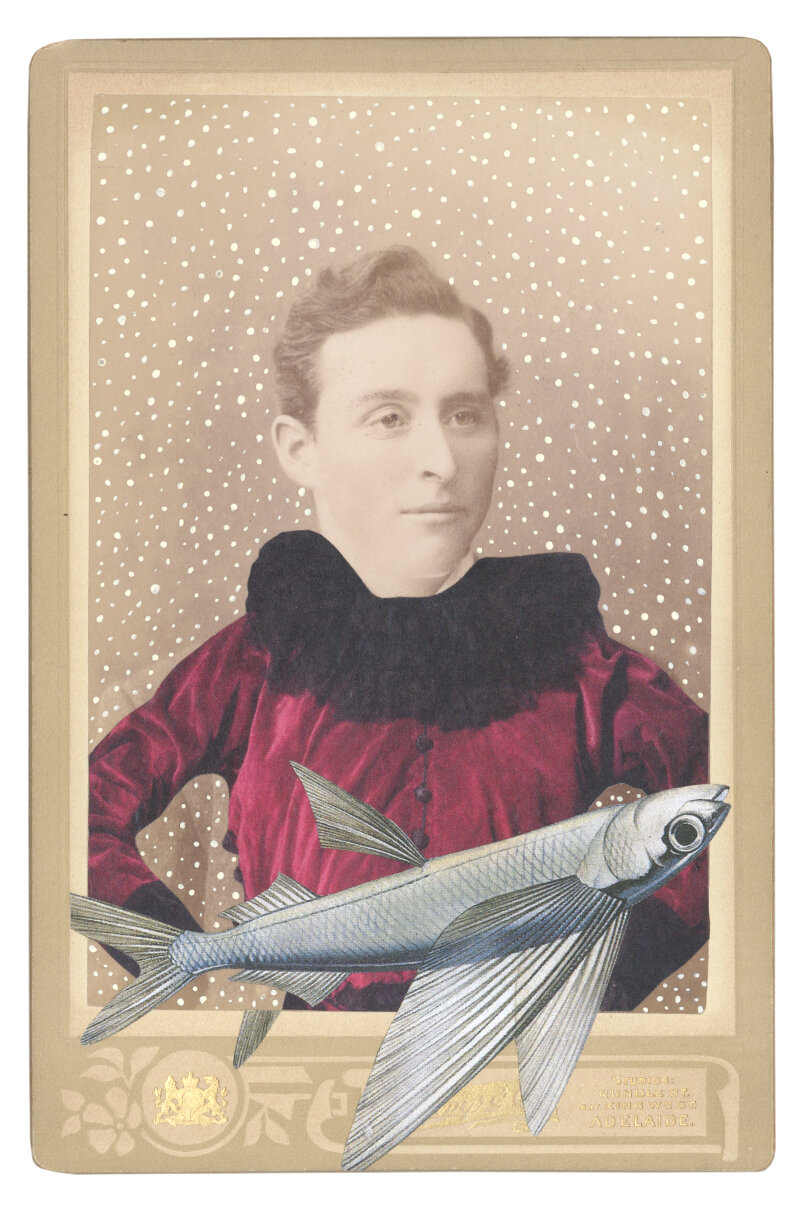

16. In the borrowed costume for a spirit of the hours from Le Pavillon d’Armide, c. 1909, designed by Alexandre Benois, with a Flying fish (Exocetus volitans)

17. In the borrowed costume of a Polovtsian Warrior, 1909–37, designed by Nicholas Roerich, with an Australian rainbowfish (Melanotaenia fluviatilis) and a Ballan wrasse (Labrus bergylta)

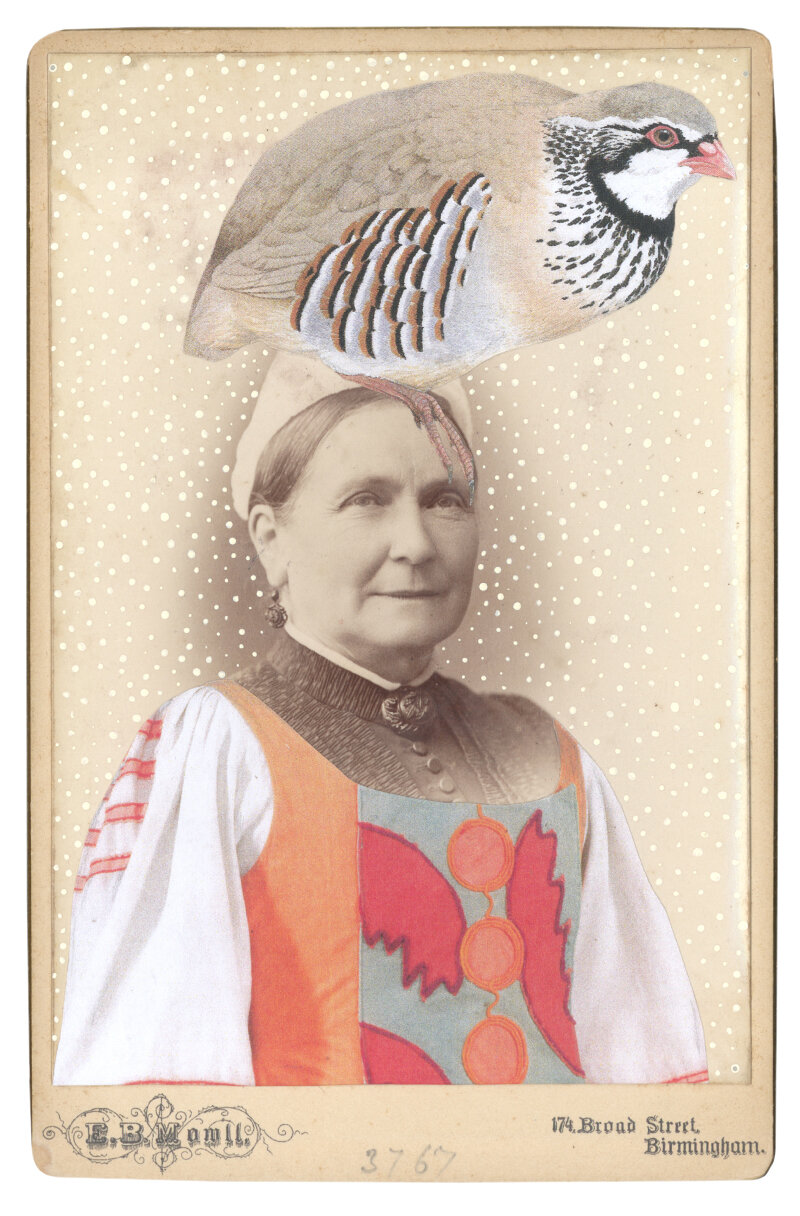

18. In the borrowed costume for a peasant woman from Le Coq d’or, c. 1937, with a Red-legged partridge (Alectoris rufa)

19. In the borrowed costume of the Chief Eunich from Schéhérazade, designed by Léon Bakst, c. 1910, with a Red spurfowl (Galloperdix spadicea)

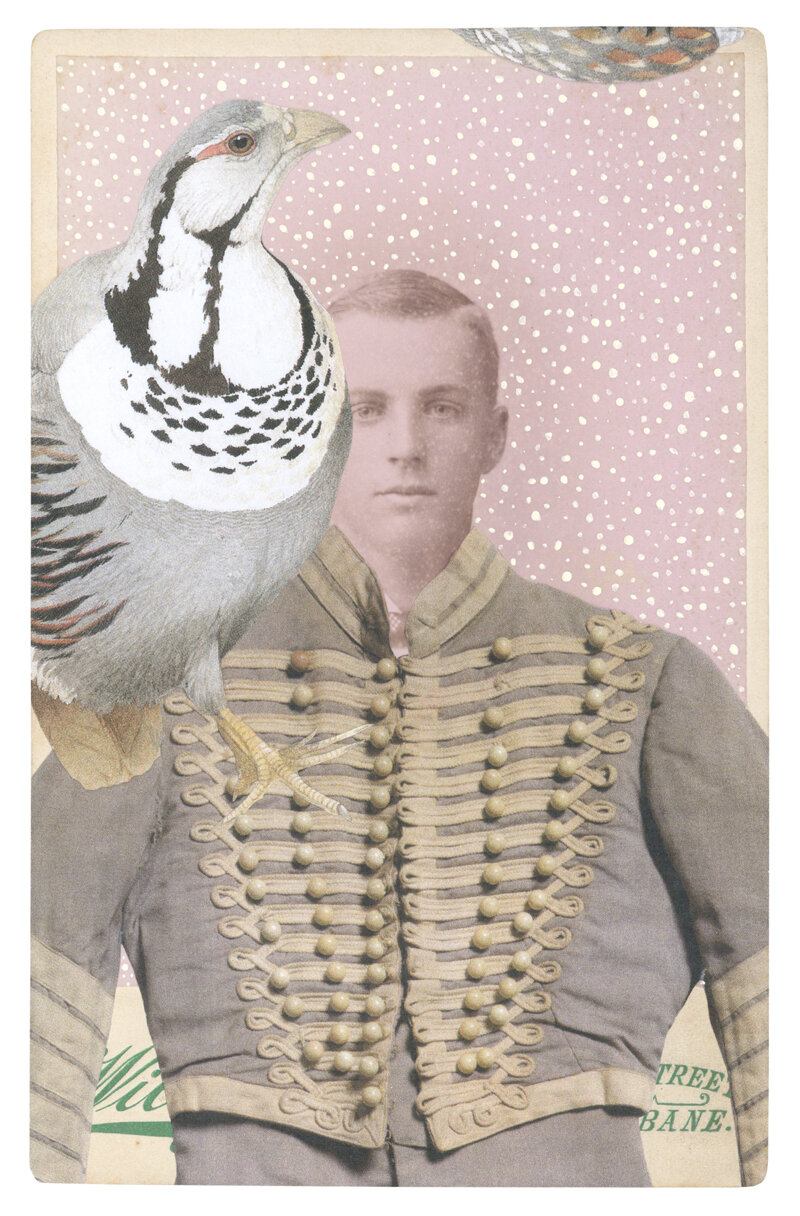

20. In the borrowed costume for the Huzzar, c. 1933, from Massine’s Le Beau Danube, with a Himalayan snowcock (Tetraogallus himalayensis)

●

Thank-you to Victor Griss of Counihan Gallery for enquiring as to the whereabouts of the In Your Dreams (2014) collages; Jurate Sasnaitis for asking when our next artists’ book launch might be; Susan Millard of the Baillieu Library for showing us the Ballet Russes treasures within the Melbourne University collection; Des Cowley for his encouragement with written word wrangling; Georgia Cribb for her kind morale-boosting; Janette and Leah Muddle of Milly Sleeping for their supreme generosity and hosting expertise; and our parents, Elaine and Peter Haby, Susan and John Jennison, for their love and constant support, always.

﹏

RELATED LINKS,

IN THE BORROWED COSTUME OF A MILITARY MUSICIAN..., SALVAGED RELATIVES COVER IMAGE CREATED FOR BOOK ARTS NEWSLETTER, NO. 93, 2014

SALVAGED RELATIVES INVITATION PDF

RELATED POSTS,

SALVAGED RELATIVES, REVIEWED

SIXTY-THREE IN NUMBER

THERE YOU WERE, IN AN OPEN SHOEBOX BENEATH THE RADIO

"THE CURTAIN FALLS"

AN INVITATION EXTENDED

COSTUMED CABINET CARDS EN MASSE

RECOVERED AND COSTUMED

SUMMER STAINED WITH GREASEPAINT

Gracia Haby & Louise Jennison

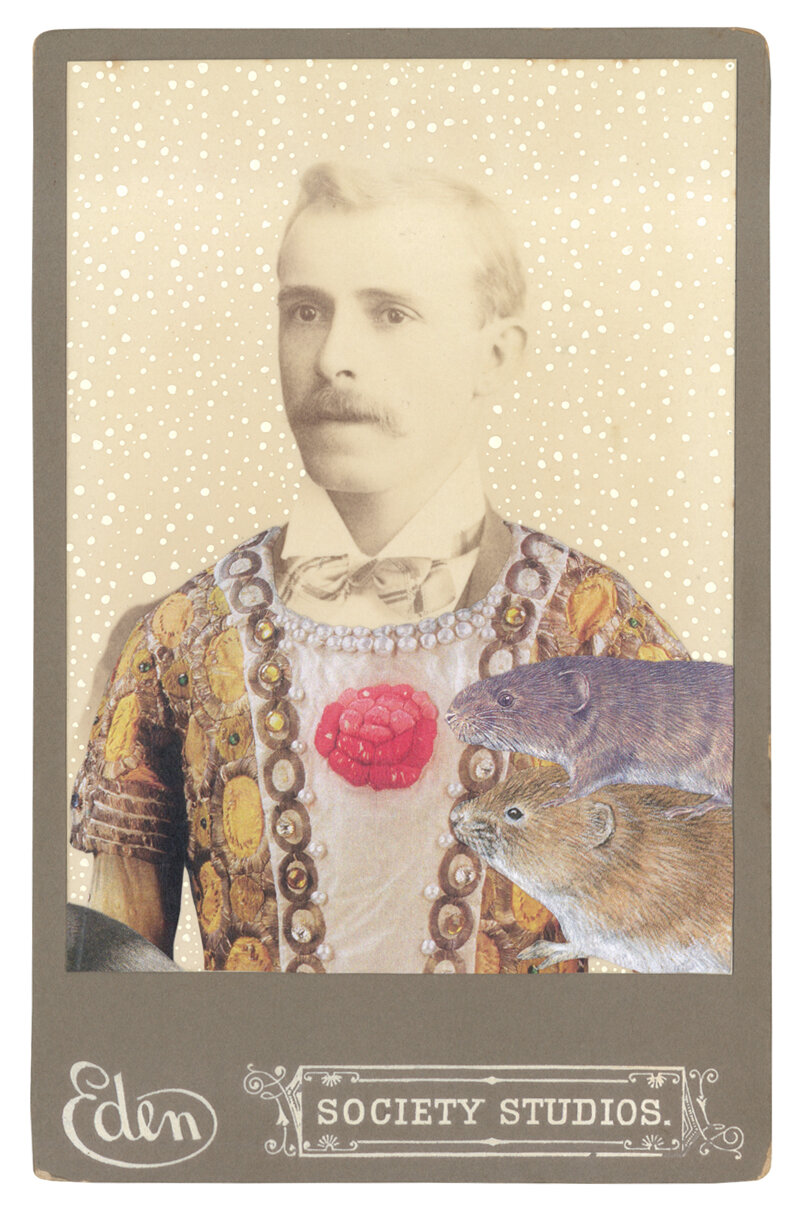

Salvaged Relatives, edition II

2014–2015

Artists’ book, unique state, featuring 21 individual collages on cabinet cards with pencil and paint additions (by Gracia Haby)

Housed in a three-colour cloth Solander box (bound by Louise Jennison) with inlaid collage, In the borrowed costume for Dr Romualdo with an Angolian talapoin (Miopithecus talapoin)

Salvaged Relatives, edition II, is in the collection of the University of Melbourne Library.

All three editions were launched as part of a One Night Only viewing on Wednesday the 11th of February, 2015, at Milly Sleeping in Carlton.

1. In the modified costume for the Prince in L’Oiseau d’Or, c. 1909, with its red raspberry temptation

2. In the stained costume of a Young Man from The Rite of Spring, c. 1913, with a Bornean smooth-tailed tree shrew (Dendrogale melanura)

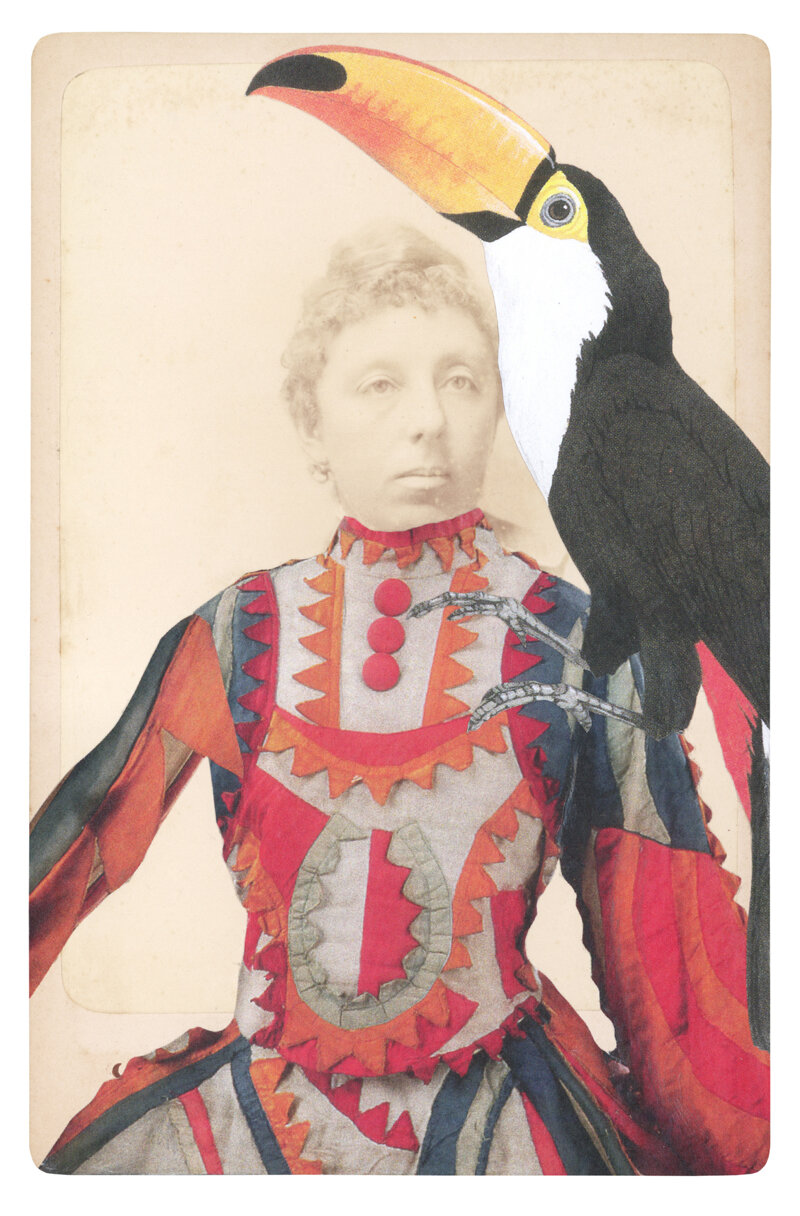

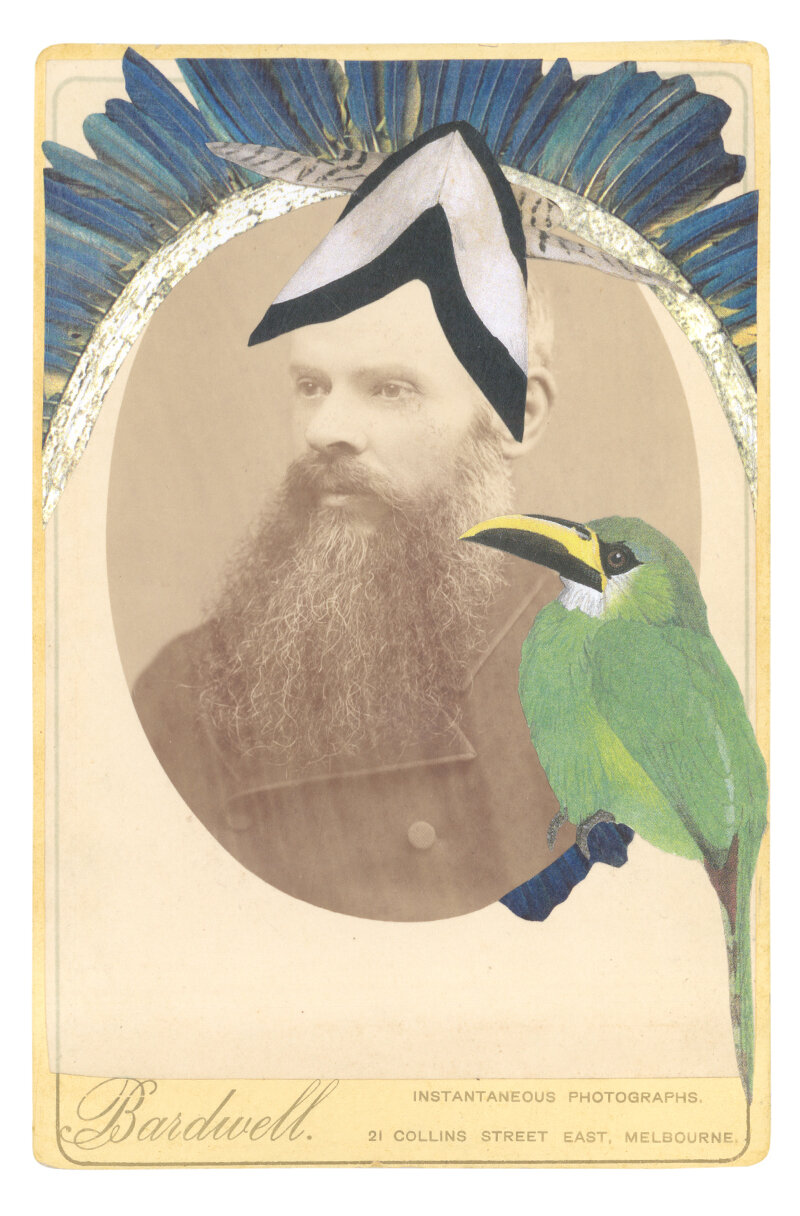

3. In the borrowed costume for the Buffoon’s Wife from Chout, with cane-stiffened felt and cotton, c. 1921, and a Toco toucan (Ramphastos toco)

4. In the borrowed costume of a Polovtsian Warrior, 1909–37, designed by Nicholas Roerich, with a Blue-winged parrot (Neophema chrysostoma)

5. In a modified headdress from a Mourner from The song of the nightingale, c.1920, designed by Henri Matisse, with an Emerald toucanet (Aulacorhynchus prasinus)

6. In the borrowed costume for a friend of Queen Thamar, designed by Léon Bakst, with a Large ground finch (Geospiza magnirostris) hovering in attendance

7. In the borrowed skirt of Columbine, c. 1942, with a Pen-tailed tree shrew (Ptilocercus lowii) and a Water opossum (Chironectes minimus)

8. In the headdress of a Seahorse, taking dictation from a Madras tree shrew (Anathana ellioti)

9. In the borrowed costume for a chamberlain from The song of the nightingale, c. 1920, with a Grey parrot (Psittacus erithacus)

10. In the borrowed costume for a court lady from The sleeping princess, c. 1921, designed by Léon Bakst, with an Emperor penguin (Aptenodytes forsteri)

11. In a borrowed tunic from Pulcinella, 1932, designed by Giorgio de Chirico, 1932, with a Pinecone fish (Monocentris japonicas) and an Emperor penguin (Aptenodytes forsteri)

12. A family portrait in the borrowed mantle from King Dodon, c. 1937, designed by Natalia Goncharova

13. In the borrowed costume for a Squid from Sadko, designed by Natalia Goncharova, c. 1916, with a Queen triggerfish (Balistes vetula)

14. In the borrowed costume of a Prince for Vaslav Nijinsky, 1914

15. In the borrowed costume for a guest from Balanchine’s Le Bal, c. 1929, with a Crossbill (Loxia curvirostra)

16. In a borrowed costume from Carnival, designed by Léon Bakst, c. 1920, with a Lumholtz’s tree-kangaroo (Dendrolagus lumholtzi)

17. In the borrowed headdress worn by Adolph Bolm as the Prince from Sadko, 1916, with a Golden mouse (Ochrotomys nuttalli)

18. In the borrowed costume for Pierrot, 1920–24, cradling an Atlantic flyingfish (Cheilopogon melanurus)

19. In a borrowed costume from Scene II of Massine’s Les Présages, c. 1933

20. In borrowed costume for a soldier from Chout, c. 1921, designed by Mikhail Larinov

Gracia Haby & Louise Jennison

Salvaged Relatives, edition III

2014–2015

Artists’ book, unique state, featuring 21 individual collages on cabinet cards with pencil and paint additions (by Gracia Haby)

Housed in a three-colour cloth Solander box (by Louise Jennison) with inlaid collage, In the borrowed costume of a Polovtsian warrior (Prince Igor c. 1909–37)

Salvaged Relatives, edition III, is in the Moreland Art Collection.

All three editions were launched as part of a One Night Only viewing on Wednesday the 11th of February, 2015, at Milly Sleeping in Carlton.

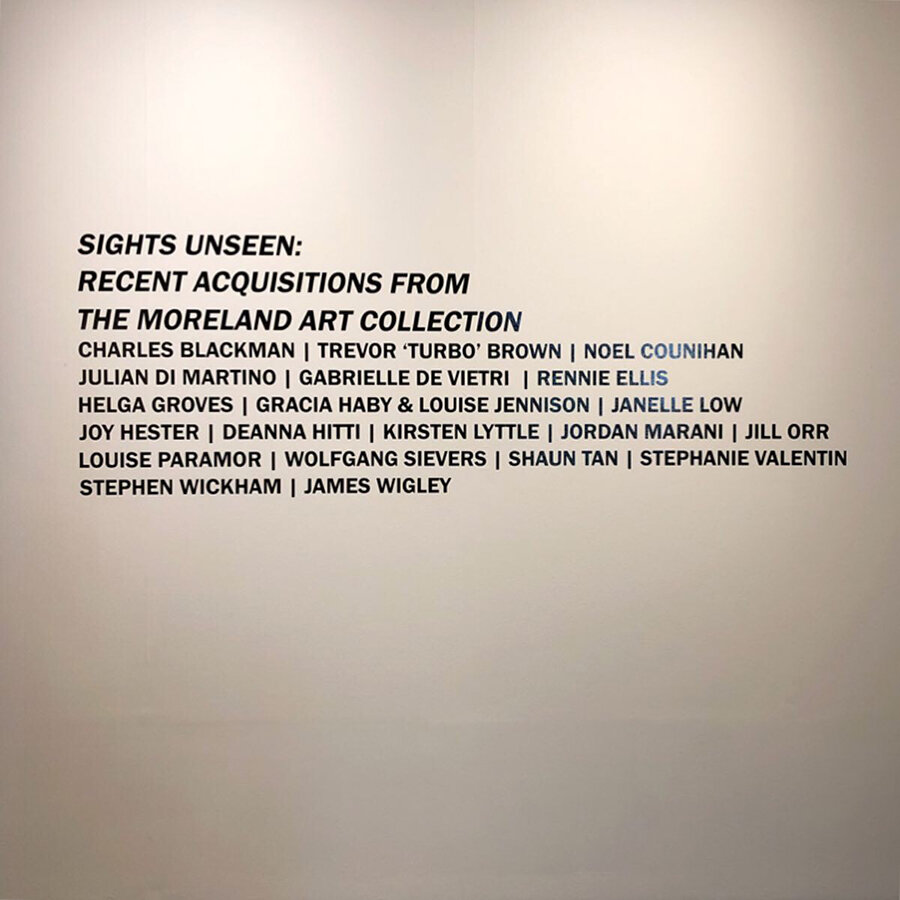

Salvaged Relatives, edition III was exhibited in Sights Unseen: Recent Acquisitions from the Moreland Art Collection, at Counihan Gallery in Brunswick alongside works by Charles Blackman, Trevor ‘Turbo’ Brown, Noel Counihan, Julian Di Martino, Gabrielle de Vietri, Rennie Ellis, Helga Groves, Gracia Haby & Louise Jennison, Joy Hester, Deanna Hitti, Janelle Low, Kirsten Lyttle, Jordan Marani, Jill Orr, Louise Paramour, Wolfgang Sievers, Shaun Tan, Stephanie Valentin, Stephen Wickham, and James Wigley. The exhibition ran until Sunday the 18th August, 2019.

1. In a borrowed cape, designed by Léon Bakst from Papillions, c. 1914

2. In the modified tunic of the Blue God, c. 1912, designed by Léon Bakst, with a Monk saki (Pithecia monachus)

3. In the borrowed costume for Lezghin, c. 1912, from Thamar

4. In the borrowed costume worn by Alice Nikitina as Flore from Zéphire et Flore, after Georges Braque, 1925, with a Cream-coloured courser (Cursorius cursor)

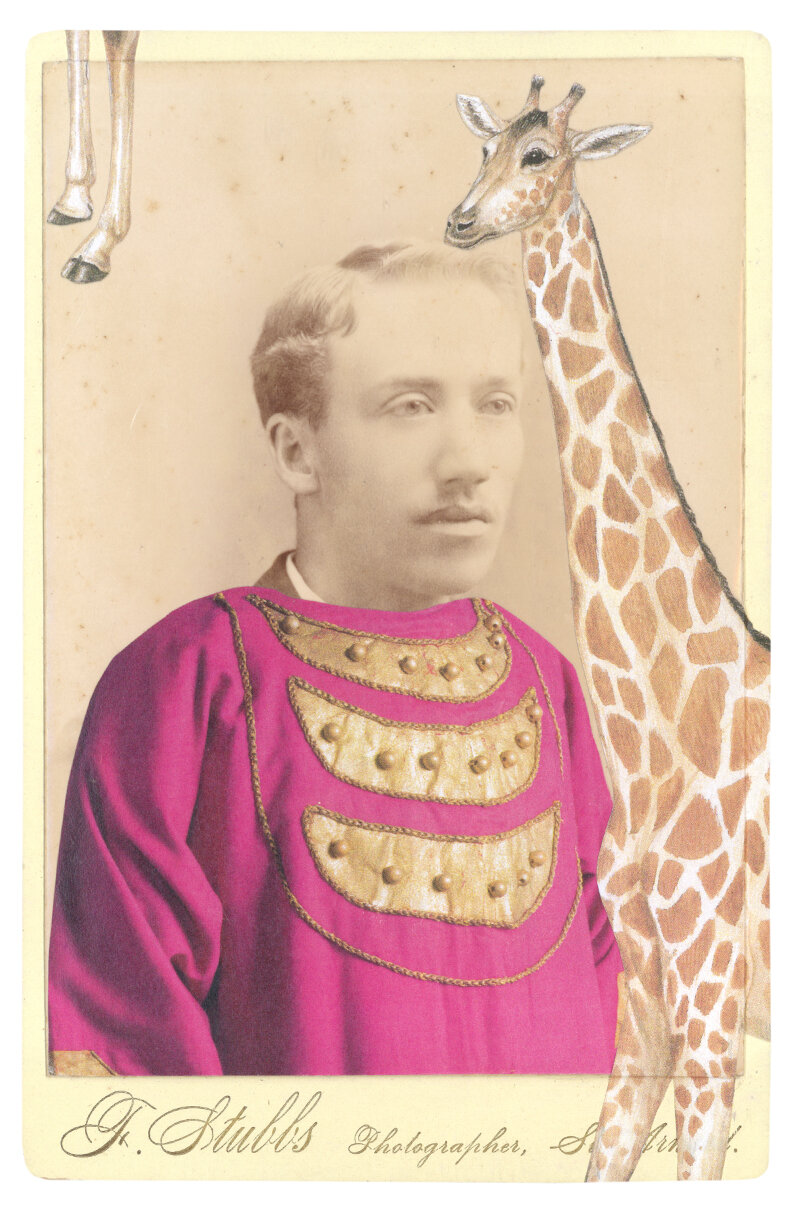

5. In a borrowed costume from The Firebird, designed by Natalia Goncharova, c. 1926, with an endangered Peralta giraffe (Giraffa camelopardalis peralta)

6. In the borrowed costume of an unspecified character from Pulcinella, 1932, designed by Giorgio de Chirico, with a Rufous-tailed plantcutter (Phytotoma rara)

7. In a modified costume from a Maiden from Vaslav Nijinsky’s The Rite of Spring, c. 1913, with a Plate-billed mountain toucan (Andigena laminirostris)

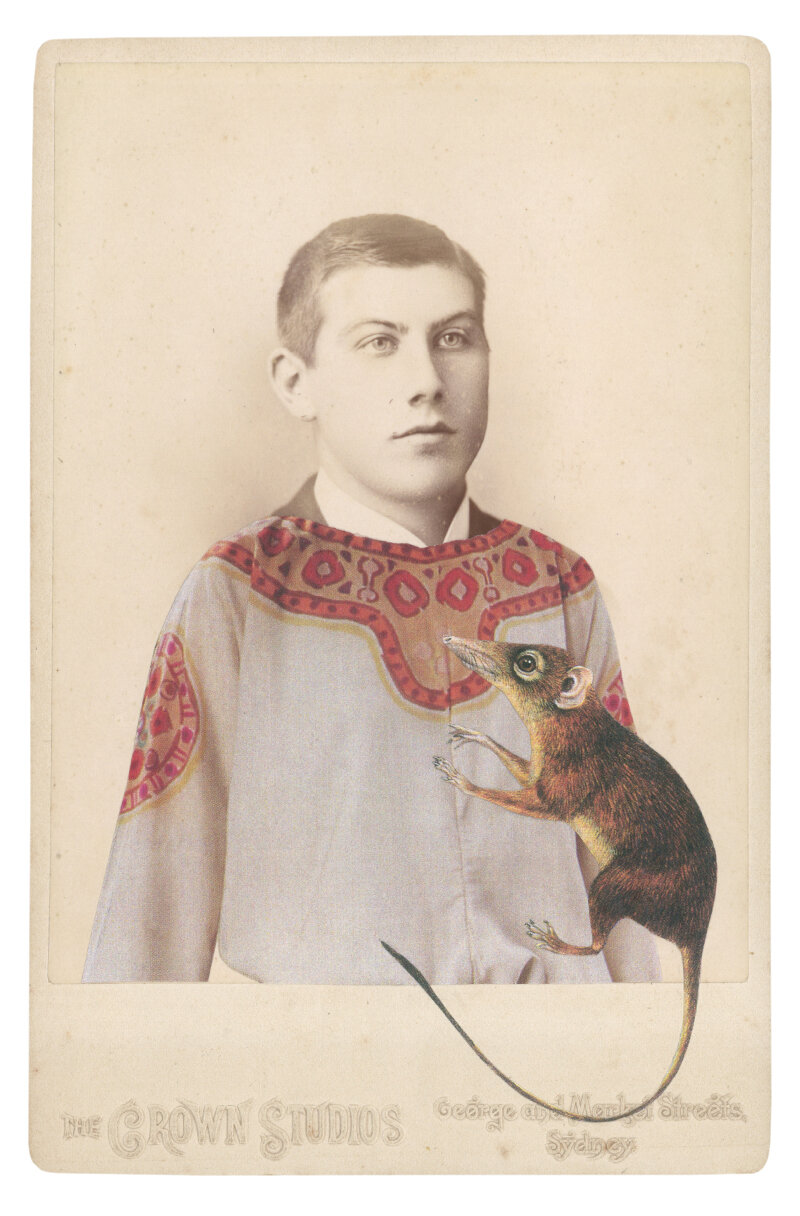

8. In the borrowed costume for a Coronation Scene from Boris Godunov for Diaghilev’s Saison Russes, c. 1908, with an Eastern barred bandicoot (Perameles gunni)

9. In the headdress of a Maiden from The Rite of Spring, 1913, with a Greater bilby (Macrotis lagotis) and a pair of Star finches (Neochmia ruficauda)

10. In a borrowed crown from Sadko, with a Grey treefrog (Hyla versicolor)

11. In the backwards costume for the Buffoon, 1921, after Mikhail Larinov, with a Curl-crested aracari (Pteroglossus beauharnaesii)

12. In the modified costume for the Prince in L’Oiseau d’Or from Le Festin, c. 1909, with a Numbat (Myrmecobius fasciatus) and a North African gerbil (Dipodillus campestris)

13. In the modified costume for a Little God from Le Dieu bleu with a brass headdress, 1912, with an Indri (Indri indri)

14. In the borrowed costume for Petrouchka, designed by Alexandre Benois, c. 1911, with a Mountain tree shrew (Tupaia montana) and a Flap-necked chameleon (Chamaeleo dilepis)

15. In the modified robe (no longer with ermine tails as decoration) for King Dodon from Le Coq d’or, c. 1937, designed by Natalia Goncharova

16. In the modified costume for a Young Man, designed by Giorgio de Chirico, c. 1929, with a Harpy fruit bat (Harpyionycteris whiteheadi)

17. After Henri Matisse, in the borrowed costume for a Courtier from The song of the nightingale, 1920, with gold studs, paint, satin, and braid

18. After David Hockney, in the borrowed costume for the Bonze from The Nightingale, 1982, with crêpe, lamé, a Greater glider (Petauroides volans) and a Blue parrotfish (Scarus coeruleus)

19. In the borrowed costume for an attendant of Köstchei from The firebird, 1910, designed by Aleksandr Golovin and Léon Bakst, with a Short-tailed opossum (Monodelphis domestica)

20. In the borrowed costume for Shah Zeman from Schéhérazade, 1910–30s, with a Swallow-tanagier (Tersina viridis)

Was it for Giorgio de Chirico’s blue hearts and yellow sleeves you pined or Cleopatra’s malachite green and flesh-toned silk, all tatty, tawdry, and crude up close?

A handful of words about cabinet cards, collage, and costume, to accompany our three artists’ books, Salvaged Relatives I, II, and III (2014–2015), at a One Night Only viewing at Milly Sleeping

Gracia Haby

2015

Salvaged Relatives notes, titles, and references (11 page PDF)

“For in and out, above, about, below,

’Tis nothing but a Magic Shadow-show,

Play’d in a Box whose Candle is the Sun,

Round which we Phantom Figures come and go.”

—Omar Khayyam[1]

There you were, in an open shoebox beneath the radio. Some eighty-odd cabinet cards that to my ego called out for salvation. Those of you less marked by age and warped by moisture, I took to the counter. A handsome, if motley, selection of sixty-three men and women, young and old, purchased as a plan for restoration formed.

Placed one atop the other and wrapped in a plastic bag, your muffled conversations hugged the corner whereas I went straight ahead and so I have no idea as to what was actually said. In the space of rustled make-believe, perhaps collectively you said you longed to take to the stage, to be part of Sergei Diaghilev’s “restless, physical slideshow”[2] steeped in the exotic, flanked by nymphs darned and patched. In the chatter, I calculated the spectacular effect. Léon Bakst was right: “People Just Want to Look!”[3]

To be reimagined as Jean Cocteau’s poster of Tamara Karsavina in profile and en pointe in Le Spectre de la rose[4]— was that one of your requests or did I project my own desire? Was it for Giorgio de Chirico’s blue hearts and yellow sleeves you pined or Cleopatra’s malachite green and flesh-toned silk, all tatty, tawdry, and crude up close? Perhaps for one of you, your hands longed to be encased in Petrouchka’s black mittens. With a ruff around your neck and pants chequered yellow, pink, and perspiration, you’d be ready for dance’s ephemerality. Perhaps it was Igor Stravinsky’s pictorial image that drew you in or the hallucinogenic qualities of Claude Debussy. Satin, paint, and tinsel, with underskirts a mass of froth! The effect, kaleidoscopic!

Shod in birch slippers, together we would become our own troupe of Natalia Goncharova’s dancing peasants, beasts, and birds. With grafted elements of ragtime and danse plastique (free dance), we needed no longer resist that “almost irresistible urge to jump up on the stage and become at one with the performance.”[5] In my hands was a deck of cards and “innumerable combinations.”[6] In my grasp, the chance to revel in Bakst’s palette of “lugubrious green [alongside] a blue full of despair.”[7]

But before the front cloth can be raised, let the highly contrived exercise begin! To beauty and tension between what is seen and what remains hidden. Yes! Here’s to that.

On the table before me, a host of characters to be dressed and belted and covered in zigzag patterns. In painted silk and felted wool dyed, stenciled, painted, and printed, you would hit no false notes. If I squinted, you were capable of constant movement. An idyll of fluid pattern! A faint line of rust upon your shoulders (from a “newly invented wire coathanger”[8]) disappeared, and the painted scallops of your skirts ruched without bulk (La Boutique fantasque). I became Maria Stepanova removing and redistributing the petals on Nijinsky still-in-costume (Le Spectre de la rose), as Picasso painted the stars on Parade’s Acrobats. In the wings, Georges Braque painted flowers on the bodice (Zéphire et Flore).

You, take these fake pearl stud earrings so heavy you can hardly hear the music.

And you, bitten by a poisonous serpent, in a costume traced with blue makeup and made of watered silk and satin, return to your celestial abode wrapped in rays of gold thread and pressed by metallic stud (The blue god).

Retire to your couch like Thamar, Queen of Georgia, waving your cerise silk scarf. Hapless suitors, be mindful of trapdoors. In the lining, I added your name below the previous entries (in the costume for a Lezghin). Clearly visible under the overhead lamp were traces of Queen Thamar’s peach-toned makeup and rotting fabric under the arms. With scissors in hand, costumes were taken in, hems shortened and side panels inserted. A miniaturized amalgam of Persian exoticism and folkloric tales unfolded before my eyes. “Majestic Shahs, kohl-eyed houris, Servile eunuchs and fierce warriors, the symbols of the seven deadly sins.”[9]

Mind your butterfly wings are not crushed (Papillons).

A battery of percussion, your soundscape: to my fickle Columbine. Upon your shoulder and at your heel, I placed the “seismographs of movement and sensitive satellites,”[10] your animal companions. A Pen-tailed tree shrew (Ptilocercus lowii) and a Water opossum (Chironectes minimus), together proved a bundle of instincts to help you navigate the wild, uncharted dream (Carnival).

To you, I give the iridescence of a marine creature, with monsters and squids in attendance (Sadko—in the underwater kingdom).

Extend your shoulders and grow your frame with stiffened buckram, felt, rubberized cloth and heavy cane you say? Of course, and in echo of the Cubist scenery, I’ll leave in my place a goat (Chout).

In your chosen attire, dragging your crinoline skirt, can you still dance the syncopated tarantella with the necessary speed?

Snip—snip—snip.

You, over there, in the stuccoed wig, your jacket and vest have become a column from the classical order. Why, you’ve become moveable architecture, an exaggerated cornice in a ballroom (Le Bal).

And you, to my right, woven tight in ikat textiles from Uzbekistan, whether your headdress slips or not, you perfectly embody the energy and new freedom of Mikhail Fokine’s choreography (The Polovtsian dances from Prince Igor).

I’ve a jumble of costumes in stock. Come as a Bluebird or a Hummingbird Fairy (The Sleeping Princess) or as a lady in waiting encased in 20 metres of dyed silk in the skirt and bodice. To Aurora’s Wedding, come as Pierrot (Women's wiles) or oversized as Dr Romualdo. In de Chirico’s overdrawn stereotypes from traditional Italian commedia dell'arte (Pulcinella), with Stravinsky echoing Giovanni Battista Pergolesi, should you want a Gabon talapoin (Miopithecus ogouensis) as a brooch, I’m in no position to refuse. Though, in principle, I oppose the use of animals as decoration. Gold braid and ermine tails! Run, Mustela erminea! I’ll swathe King Dodon in eight layers of fabric to make good your escape (Le Coq d’or).

Take your cue from Leonide Massine’s Les Presages and be not anchored to a particular time and place. Become a singular organism of bitter colour orchestration constructed in Diaghilev’s legacy. Or fall back to Vienna’s formal elegance in the height of summer, 1860, in Le Beau Danube dressed as the Hussar. Let’s!

Or perhaps you prefer the idea of weaving yourself into the fabric of a park at dusk, your coin purse stolen as you reminisce about a love affair (Jardin public). Okay.

Snip—snip—snip.

Will you take your tragedy from Canto V of Dante’s Inferno (Francesca da Rimini), throwing yourself onto your husband’s sword?

Will you be held in place by Henri Matisse’s chevrons of navy blue velvet, an exotic bird from his own collection perhaps (The song of the nightingale)?

Will, like Vaslav Nijinsky, you take your choreography from a toy duck with its “weighty, angular, downward thrust”[11] (The Rite of Spring)?

Become stateless, travelling on Nansen passports, my troupe. Become Irina Baronova advertised on a De Reszke cigarette card. Or slink into an Æsop’s fable and become the cat-woman in pursuit of a mouse. “Mrkgnao! the cat cried”[12] (La Chatte). Perhaps the magically feathered half-woman and half-bird of Slavic folklore born aloft not by strings but by music[13] feels your path. Mind there’s a soul hidden in that egg (The firebird).

Grow larger still. Spring from cabinet card to a gelatin silver photograph. Be Icarus as he falls to the ground (Icare[14]). I’ll cushion your knees.

A backdrop for your enchantment has been provided. Be lined with vermillion. Be weighted with gold acorns (Narcissus). With its chronological assortment of stains, let us reduce that skirt and remove that trimming. With white spots on the backcloth to echo Fokine’s choreographic floor patterns repeatedly layered, not for you the painful misfortune of falling through a rotting floorboard and tearing an Achilles tendon like Alexander Gavrilov.

My Salvaged Relatives, tucked inside a fairy tale inside a Solander box-nest where old age and weary muscles will not find you.

Snip—snip.

“The curtain falls.”[15]

Endnotes:

[1] Khayyam, Omar, poem in Beaumont, Cyril, decorated by Sevier, Michel, Impressions of the Russian Ballet 1919: Petrouchka, edition 38/40, London: C. W. Beaumont, 1919, p.5.

[2] Goodall, Howard, ‘Music and the Ballets Russes’ in Pritchard, Jane (Ed.), Diaghilev and the Golden Age of the Ballets Russes 1909–1929, London: V&A Publishing, 2010, p.176.

[3] Bakst, Léon, ‘O sovremennom teatre. “Nikto v teatre bol’she ne khochet slushat, a khochet videt!”’, Petersburgskaia gazeta [The Petersburg Gazette], 21st of January 1914, no.20, p.5., referenced by Bowlt, John, E., ‘Léon Bakst, Natalia Goncharova and Pablo Picasso: “Call Forth Emotions by Captivating the Eye”’ in Diaghilev and the Golden Age of the Ballets Russes 1909–1929, p.105.

[4] One of two large-scale, colour lithographic posters for the opening season of the Théatre des Champs-Elysées, Paris, 1913, originally created by Jean Cocteau for the 1911 season at Monte Carlo. The other was of Vaslav Nijinsky, who Cocteau described as having a “slender young torso contrasting with overdeveloped thighs, ... like some Florentine, vigorous beyond anything human, and feline to a disquieting degree.” V&A Theatre and Performance Collection, http://collections.vam.ac.uk/item/O75904/ballets-russes-poster-cocteau-jean/, accessed online 7th January, 2015.

[5] Bowlt, John, E., ‘Léon Bakst, Natalia Goncharova and Pablo Picasso: “Call Forth Emotions by Captivating the Eye”’ in Diaghilev and the Golden Age of the Ballets Russes 1909–1929, p.103.

[6] “The costumes might intervene with each other mutually or come forth one from the other. One costume, put next to another might hardly be noticed... This [process] can be compared to a game of cards with its rigid and complex rules and innumerable combinations.” Goncharova, Natalia, Le Costume Théatral (1930), in Diaghilev and the Golden Age of the Ballets Russes 1909–1929, p.108.

[7] Léon Bakst discussing his “paradoxical” colour palette for Schéhérazade, Diaghilev and the Golden Age of the Ballets Russes 1909–1929, p.104.

[8] Ward, Debbie, ‘Sights Unseen: Tags, Stamps and Stains’, in Bell, Robert, Ballet Russes: The Art of Costume, Canberra: National Gallery of Australia, 2010, p.199.

[9] Beaumont, Cyril, decorated by White, Ethelbert, Impressions of the Russian Ballet 1919: Thamar, edition 30/40, London: C. W. Beaumont, 1919, p.5.

[10] Luc Van Den Dries discussing animals in a conversation with Jan Fabre, 2004/2003, in Lepecki, André (Ed.), Dance: Documents of Contemporary Art, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2012, p.123.

[11] Edwin Evans recalls of Vaslav Nijinsky: “Like many artists he had a weakness for clever toys. I discovered in Chelsea a jointed wooden duck which was capable of assuming extraordinary expressive angular attitudes. I procured one for him, and he was delighted with it. The following year, after The Rite of Spring had been produced with his angular choreography, one of his first questions to me was: ‘Well, did you recognize it?’ — ‘What?’ — ‘Why, the duck, of course’, and he told me that some of the most effective angular poses in the ballet had originated with the duck.” Pritchard, Jane, ‘Creative Productions’, in Diaghilev and the Golden Age of the Ballets Russes 1909–1929, p.81.

[12] Joyce, James, Ulysses, Gabler, Hans Walter (Ed.), with Steppe, Wolfhard, & Melchior, Claus, London: The Bodley Head, 2008, p.45.

[13] “It is easily possible to hear the flight of the bird, its approach and play among the branches of the magic tree, and capture by the prince.... an atmosphere of witchcraft, goblins, and attendant magic.” Beaumont, Cyril, decorated by White, Ethelbert, Impressions of the Russian Ballet 1919: L’Oiseau de Feu, edition10/46, London: C. W. Beaumont, 1919, p.6.

[14] Beck, Vene, Stage performance of Icare (Icarus falls to the ground), 1940, gelatin silver photograph, 16.6 X 24.6 cm, National Gallery of Australia

[15] Beaumont, Cyril, decorated by Allinson, Adrian, P., Impressions of the Russian Ballet 1919: Schéhérazade, edition 18/40, London: C. W. Beaumont, 1919, p.13.

References:

Beaumont, Cyril, decorated by Sevier, Michel, Impressions of the Russian Ballet 1919: La boutique fantasque, edition 10/40, London: C. W. Beaumont, 1919.

Beaumont, Cyril, decorated by Allinson, Adrian, P., Impressions of the Russian Ballet 1918: Carnaval, edition 22/40, London: C. W. Beaumont, 1918.

Beaumont, Cyril, decorated by Sevier, Michel, Impressions of the Russian Ballet 1919: Children’s Tales, edition 1/40, London: C. W. Beaumont, 1919.

Beaumont, Cyril, decorated by Allinson, Adrian, P., Impressions of the Russian Ballet 1919: Cleopatra, edition 10/46, London: C. W. Beaumont, 1919.

Beaumont, Cyril, decorated by Allinson, Adrian, P., Impressions of the Russian Ballet 1918: The Good Humoured Ladies, edition 22/40, London: C. W. Beaumont, 1918.

Beaumont, Cyril, decorated by White, Ethelbert, Impressions of the Russian Ballet 1919: L’Oiseau de Feu, edition 10/46, London: C. W. Beaumont, 1919.

Beaumont, Cyril, decorated by Sevier, Michel, Impressions of the Russian Ballet 1919: Petrouchka, edition 38/40, London: C. W. Beaumont, 1919.

Beaumont, Cyril, decorated by Allison, Adrian, Impressions of the Russian Ballet 1919: Schéhérazade, edition 18/40, London: C. W. Beaumont, 1919.

Beaumont, Cyril, decorated by Schwabe, Randolph, Impressions of the Russian Ballet 1921: Sleeping princess, part one, edition 13/40, London: C. W. Beaumont, 1921.

Beaumont, Cyril, decorated by Schwabe, Randolph, Impressions of the Russian Ballet 1921: Sleeping princess, part two, edition 10/40, London: C. W. Beaumont, 1921.

Beaumont, Cyril, decorated by White, Ethelbert, Impressions of the Russian Ballet 1919: Thamar, edition 30/40, London: C. W. Beaumont, 1919.

Beaumont, Cyril, decorated by White, Ethelbert, Impressions of the Russian Ballet 1919: The Three-cornered Hat, edition 40/40, London: C. W. Beaumont, 1919.

Bell, Robert, Ballet Russes: The Art of Costume, Canberra: National Gallery of Australia, 2010.

Brunoff, Maurice de, Collection des plus beaux numéros de Comoedia illustré et des programmes consacrés aux ballets & galas russes : depuis le début à Paris, 1909–1921, edition 10/40, Paris: M. de Brunoff, 1922.

Joyce, James, Ulysses, Gabler, Hans Walter (Ed.), with Steppe, Wolfhard, & Melchior, Claus, London: The Bodley Head, 2008.

Lindsay, Daryl, Back stage with the Covent Garden Russian ballet, Sydney: Peerless Press, 1938.

Lepecki, André (Ed.), Dance: Documents of Contemporary Art, Massachusetts: The MIT Press, 2012.

Pritchard, Jane (Ed.), Diaghilev and the Golden Age of the Ballets Russes 1909–1929, London: V&A Publishing, 2010.

Propert, Walter Archibald, The Russian ballet in western Europe, 1909–1920, edition 315/500, New York: John Lane, 1921.

Svietlov, Valerian, translated from the Russian by Grey, A., Anna Pavlova, Paris: M. de Brunoff, 1922.

Turner, Walter James, Britain in pictures, English ballet, London: W. Collins, 1946.

V&A Theatre and Performance Collection, http://collections.vam.ac.uk/.

Salvaged Relatives: New work by Gracia & Louise

Milly Sleeping, Melbourne, 11th February, 2015

Review by Alice Cannon

Centre for Fine Print Research, UK

Book Arts Newsletter, mid-April – June 2015, issue 97

pp. 50–51 (pdf download)

If you are the type of person who likes to lose yourself in second-hand shops and junk markets, you will be familiar with a certain type of object: a faded photographic portrait of a person in 19th-century dress, pasted onto thick card. The name of the photographer’s studio is probably stamped on the bottom of the mount, but the identity of the sitter is usually unknown — unless a rare handwritten inscription on the reverse gives some clue. At some point these visages from the past have become separated from their descendants, too far-removed from those who loved them, and they have been sold or thrown away.

I always feel a bit sad when I find them, for it is the inevitable fate of most of us — our lives forgotten, our likenesses discarded. These objects are cabinet cards, a format first introduced in the 1860s. Initially the portraits were made using albumen photographic paper, where the image layer was made of egg white sensitized with silver salts. Over time, albumen prints tend to brown and fade, sometimes also acquiring a smattering of pale spots, like cream-coloured measles. The popularity of cabinet cards waned at the turn of the century, when the Kodak Box Brownie camera put photography in the hands of everyone.

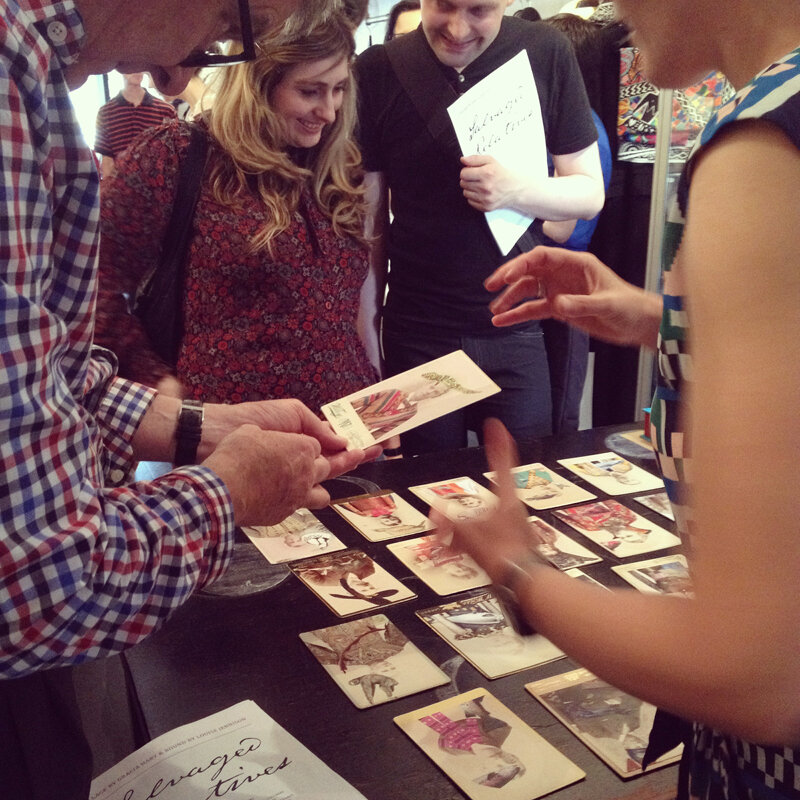

Gracia Haby and Louise Jennison seek to reclaim some of these lost souls. In February Melbournites were treated to a one-night-only viewing of Gracia & Louises’ latest work, Salvaged Relatives. The exhibition consisted of three artists’ books, each a unique state, and each featuring 21 individual collages on cabinet cards with pencil and paint additions. Each set is housed in a beautiful linen Solander box (one red, one yellow and one blue), the lid of each inlaid with one collage. As ever, the work of Gracia and Louise is both technically exquisite and imaginatively dreamlike. The viewing was held at Milly Sleeping, a clothing boutique specialising in locally-made clothing, accessories and jewelry from designers in Australia and New Zealand. Owners Janette and Leah have long been supporters of Gracia & Louise and their petite store provided a perfect venue for viewing such intimate work.

Haby has clothed the three sets of anonymous folk in the luxurious costumes of the Ballet Russes, which were inspired by artists such as Natalia Goncharova, Pablo Picasso and Georges Braque, and the fairytale music of Rimsky-Korsakov, Debussy and Stravinsky. Our salvaged relatives now also have birds and beasts as companions. A fish peeks out from the gold brocade jacket of a mustachioed gentleman. Another portrait features a mysterious man in a blue cloak and a zebra disappearing stage right. A serious woman with a severe part looks past the songbird on her shoulder. And in one of the more ambiguous images, a lady appears to be sprouting a tail from underneath her skirts.

Viewers of the exhibition of course had their favourites. Some were attracted to a particular costume, colour or animal. Others were intrigued by the look of a person, wondering at the thoughts and passions hiding behind their serious expression. Whatever the reason, we all started to wonder about the person in the photograph — what were they like, and what had they done on that day, before this portrait was taken? Would they have been delighted at their new clothes, or terrified by the presence of an aardvark, giraffe or gecko in close proximity to their person?

In the artists’ notes Haby writes, ‘My Salvaged Relatives, tucked inside a fairy tale inside a Solander box-nest where old age and weary muscles will not find you.’ For the forgotten this is a re-awakening. We have recognised them once again as individuals, as people with hopes and fears, as real, and not just dusty objects in a shop window.

Alice Cannon is a paper and photograph conservator. She is also the editor of Materiality, through pinknantucket press.