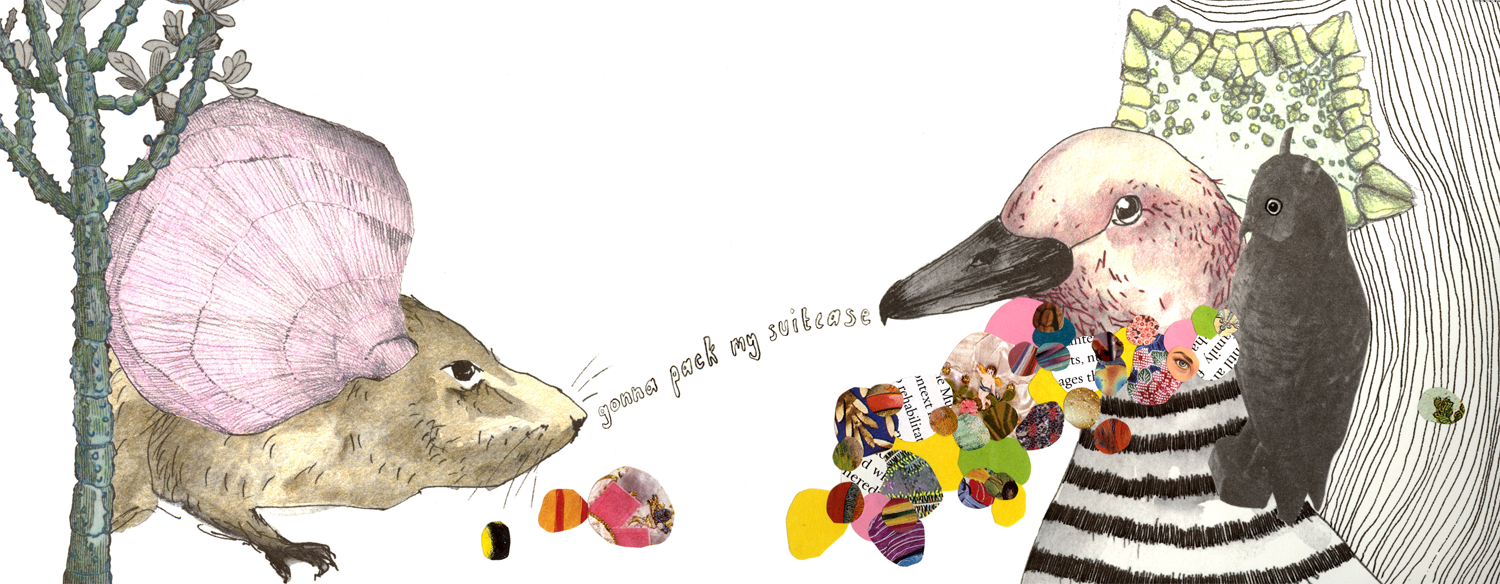

AND THEY SILENTLY STEAL AWAY

Gracia Haby & Louise Jennison

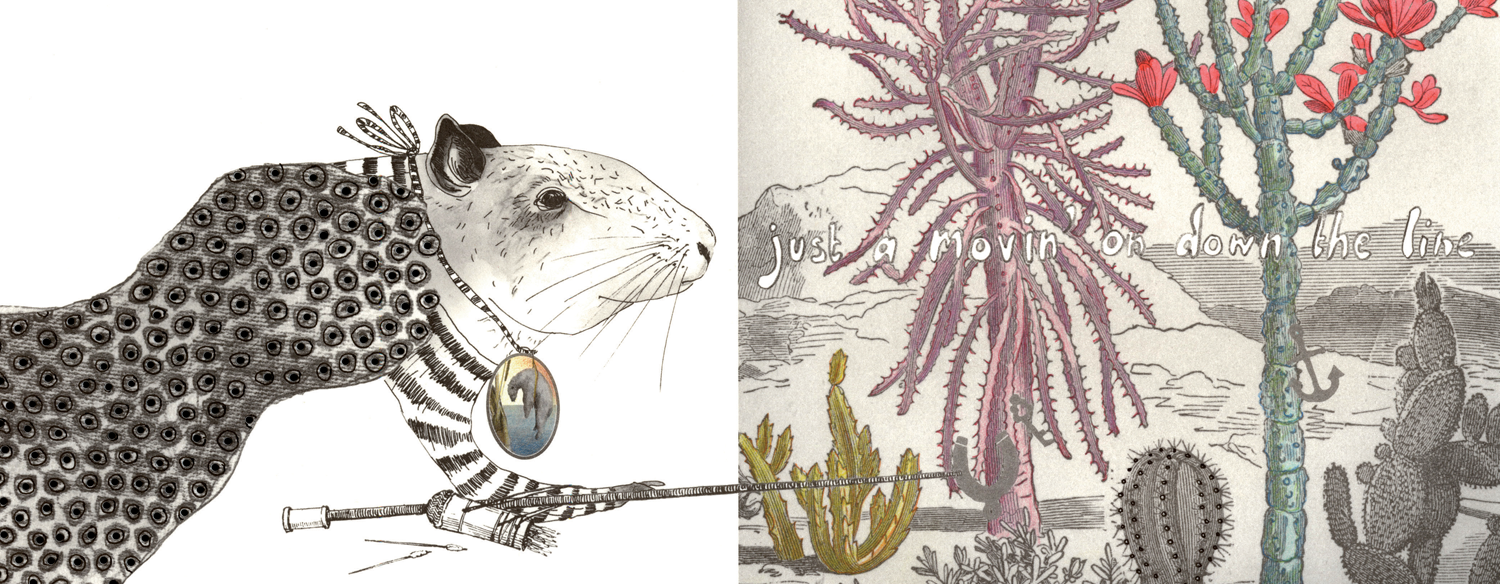

And they silently steal away

2005

Single-color lithographic offset print hand colored with pencil and collage on Spicers cotton 270gsm, 46cm X 30cm

Printed by Redwood Prints

Edition of 25, with two artists’ proofs

A print created as part of the Summer Studios @ 66 (now known as the Print Imaging Practice Residency) RMIT summer residency programme and exhibited as part of Ex Libris (2005), accompanied by our artists’ books, The Case of the Lost Aviary, Trouble at Sea, The Dubious Clue, and By the Pricking of My Claws.

JUSTIN CALEO, GRACIA HABY & LOUISE JENNISON, JESSICA IRVIN, MARION MANIFOLD, JENNIFER MILLS, JULIA SILVESTER, KATE ZIZYS

EX LIBRIS

MONDAY 28TH OF NOVEMBER – FRIDAY 16TH OF DECEMBER, 2005

CURATED BY JAZMINA CININAS

PROJECT SPACE – SPARE ROOM, RMIT UNIVERSITY, RMIT BUILDING 94, LEVEL 2, ROOM 1, 23–27 CARDIGAN STREET, CARLTON

An extract from the Ex Libris catalogue essay

Jazmina Cininas

October 2005

The 19th century author Henri Bouchon poetically defined the ex libris as: …the oldest mark of men’s sincere love for [their] literary property. It is the coat of arms of the spirit, a beautiful and original manner of showing ownership which has no other explanation than…love for the book.[1]

Small enameled tablets dating from around 1400 BC identify papyri as belonging to Pharaoh Amenophis III’s library, these earliest of ex libri attesting to the long-standing love affair between mankind and books.[2] It is the illustrated book that has proved particularly seductive to the eight Ex Libris artists. In defiance of common academic and cultural elitism against all things ‘illustrative’, these artists champion pictorial depictions and narratives, acknowledging their debt to, and celebrating their affection for, the illustrator.

Gutenberg’s invention of the mobile-type printing press has been described as the greatest influence on the development of mankind,[3] but Pfister’s 1461 innovation, which allowed for the printing of pictures alongside the typographic texts, cannot be underestimated.[4] The life sciences gained a new status[5] once the illustration commanded the leading role in building the professional knowledge of architects, engineers, anatomists, botanists, and zoologists[6], challenging Classical privileging of ideas and text over image.[7]

.…

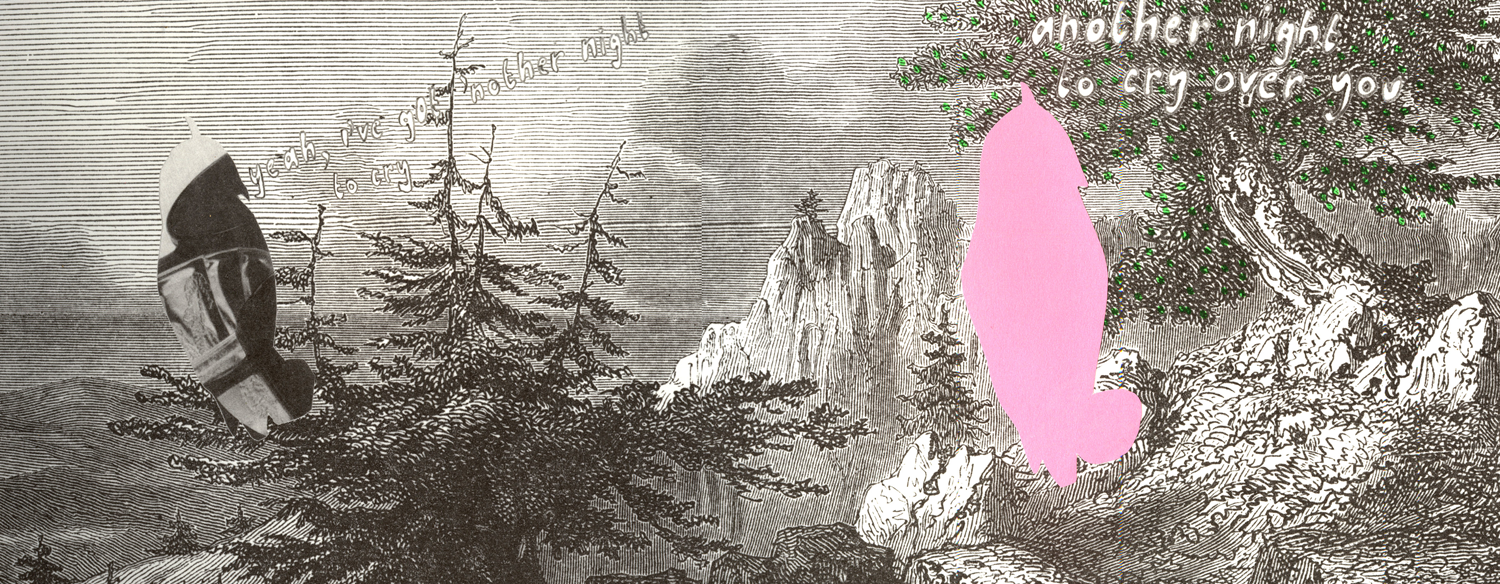

Gracia Haby and Louise Jennison employ an equally slippery approach to ‘facts’, creating whimsical narratives about disappeared species that operate according to their own logic. The printing process, as both a technical and artistic activity, has been linked not only to the memory of human thought, but also to the memorial process.[23] Haby & Jennison’s artist’s books employ digital collages of drawings and found illustrations, mediated through offset lithography, to pay tribute to extinct creatures. Their Christie-esque book titles — By the Pricking of My Claws; The Case of the Lost Aviary; Trouble at Sea; The Dubious Clue — attest to Haby & Jennison’s delight in amateur detective work. Unearthing sad tales such as that of the Passenger Pigeon (once so numerous flocks blackened the skies for hours, but lured to extinction by alcoholic grain and captive pigeons with their eyes sewn shut) and stumbling across incriminating evidence against ship-jumping black rats[24], Haby & Jennison conjure new, pseudo-scientific scenarios. James Atlas might have been describing the artists’ work when he observed: “The truth is in the prose, the style, the quality of presentation that compels us to believe”.[25]

Haby & Jennison’s truth is, by necessity, a fabrication — the species themselves being lost for all time, leaving only fragmentary data from which to glean information. Their Rabbit rats, Pig-footed bandicoots, Deer mice and Bulldog rats are as fanciful as their names suggest, sporting sailing boats for headgear or fossils as body parts. Extinct Cloud Runners and Pink-Headed Ducks sing the blues according to Memphis Slim, sporting jail break outfits as they go fishing amongst the desert cacti, taking liberties with the argument that “narrative metaphors are an indispensable part of all “factual” discourse, whether in history or in science”,[26] and winking at the commonly held notion that the historian’s work is partly scientific, partly artistic.[27]

….

The artists in Ex Libris all, in various ways, employ illustrative conventions to create new fictions, and new truths. The artifacts they produce draw from personal libraries, testifying to the illustrated book's enduring capacity for inspiring creative acts[35] and for capturing the evolution of the human spirit.[36]

The research team of Joseph Jacobson is working on the concept [of] a printing surface that can be infinitely printed upon...It is his vision that in the not-too-distant future every child will be given his or her “Last Book”.…[37] One suspects that Caleo, Haby & Jennison, Irvin, Manifold, Mills, Silvester and Zizys imagine a somewhat different future.

[1] José Miguel Valderrama, EX LIBRIS (Bookplate): A secret bond of affection between the book and its owner, http://www.geocities.com/andaluzadexlibristas/ExlibrisIngles.htm, viewed 21 October 2005.

[2] From earliest times, books have always been cherished and jealously guarded by their owners [being regarded as] privileged vehicles of knowledge, and prized possessions. Benoît Junod, “Ex-Libris Or The Mark Of Possession Of Books”, The World Of Ex-Libris: A Historical Retrospective, http://www.karaart.com/prints/ex-libris/index.html, viewed 21 October 2005.

[3] “No invention has had a greater influence on the development of mankind than that of printing.” Ibid.

[4] See A. Hyatt Mayor, “Herbals and scientific illustration” and “Printing breaks away from manuscript”, Prints & People: A Social History of Printed Pictures, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 1971.

[5] “By paying more attention to the duplication of pictorial statements, we might see more clearly why the life science no less than the physical ones were placed on a new footing and how the authority of Pliny, no less than Galen and Ptolemy, was undermined.” Elizabeth l. Eisenstein, The Printing Press as an Agent of Change: Volume II, Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 1979, p.686.

[6] See Hyatt Mayor, “Printing breaks away from manuscript.”

[7] “New ways of picture making changed the very basis of knowledge. The Greeks and Romans...scorned the instability of appearances, whose images shifted when repeated through the only replication then known. Today the emphasis is reversed.” Ibid, “Herbals and scientific illustration.”

[23] “Printing as Memory”, a pair of lectures delivered by Alvin Eisenman at Dartmouth in 1992 imply in their title “not only the idea of printed texts as the memory of human thought but also the role of printing, as a technical and artistic activity, in the memorial process.” G. Thomas Tanselle, “Printing History and Other History”, Studies in Bibliography, Volume 48 (1995), p.289.

[24] Information on the passenger pigeon and the rats was supplied to the author by the artists, October 2005, citing Clive Ponting, A Green History of the World, Penguin Books, 1992: http://www.ulala.org/P_Pigeon.html: and Tim Flannery & Peter Schouten, A Gap in Nature — Discovering the World’s Extinct Animals, Text Publishing Australia, 2001.

[25] Tanselle

[26] Donald N. McCloskey, cited in ibid.

[27] See G. M. Trevelyan, cited in ibid.

[35] “..the effects produced by printing may be plausibly related to an increased incidence of creative acts…”, Eisenstein, p.688.

[36] Our best chance of capturing the human spirit…is through studying the artefacts it has produced…Printing history is essential for examining a major class of those artefacts by helping us to decipher, in the fullest way possible, the physical marks that constitute verbal messages from the past. Tanselle, p.289.

[37] Stephan Fussel, “Gutenberg and Today's Media Change”, Publishing Research Quarterly, Winter 2001, Vol.16, Issue 4, p.p. 3–11.

And they silently steal away was later exhibited at Spare Room in 2013, alongside all prints created as art of the RMIT Print Imaging Practice Residency. Since 2004, the RMIT School of Art Galleries and the RMIT School of Art Print Imaging Practice Studio have collaborated to invite artists to take part in an annual residency. Artists are provided with access to the printmaking and photography facilities and with materials to create an original edition of prints.

DECISIONS: THE PRINT IMAGING PRACTICE RESIDENCY EXHIBITION 2013

FRIDAY 1ST OF NOVEMBER TO THURSDAY 5TH OF DECEMBER, 2013

SPARE ROOM, RMIT UNIVERSITY, RMIT BUILDING 94, LEVEL 2, ROOM 1, 23–27 CARDIGAN STREET, CARLTON

INCLUDES ARTWORK BY ROSALIND ATKINS, GRAHAM BADARI, BELLE BASSIN, URSULA BOLCH, JUSTIN CALEO, ALEX CARROLL, ANGELA CAVALIERI, JAZMINA CININAS, ANNETTE COOK, JASON COTTER, ANTONIETTA COVINO-BEEHRE, STEVE COX, LINDA ERCEG, MICHAEL FLORRIMELL, MARCO FUSINATO, JOEL GAILER, STEPHEN GALLAGHER, TONY GARIFALAKIS, NATHAN GRAY, RONA GREEN, GRACIA HABY & LOUISE JENNISON, IRENE HANENBERGH, RICHARD HARDING, KATHERINE HATTAM, EUAN HENG, ANNA HOYLE, JESSICA IRVIN, KATE JAMES, LOUISA JENKINSON, RUTH JOHNSTONE, SHANE JONES, KATE JUST, DEBORAH KLEIN, DAMON KOWARSKY, MARION MANIFOLD, GEORGE MATOULAS, MARK MCDEAN, JENNIFER MILLS, DAVID NOONAN, CRISTINA PALACIOS, SIMON PERICICH, KERRIE POLINESS, REKO RENNIE, KIRON ROBINSON, JONAS ROPPONEN, STACEY RYAN, ERIK MARK SANDBERG, ALEX SELENITSCH, HEATHER SHIMMEN, JULIA SILVESTER, ANDREW SINCLAIR, STEPHEN SPURRIER, KATE STONES, KRISTINA SUNDSTROM, SOPHIA SZILAGYI, DEB TAYLOR, ANDREW TETZLAFF, MICHAEL VALE, DEBORAH WILLIAMS AND KATE ZIZYS

﹏

RELATED LINK,

FOR MARTHA, AN ARTISTS' BOOK BY LOUISE JENNISON, 2011–2012

RELATED POSTS,

(NO) SPARE ROOM

ONCE, TWICE, TAGGED