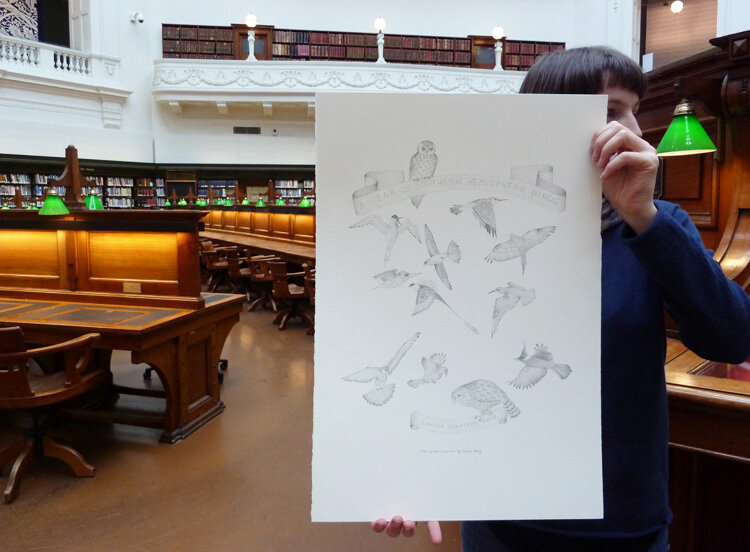

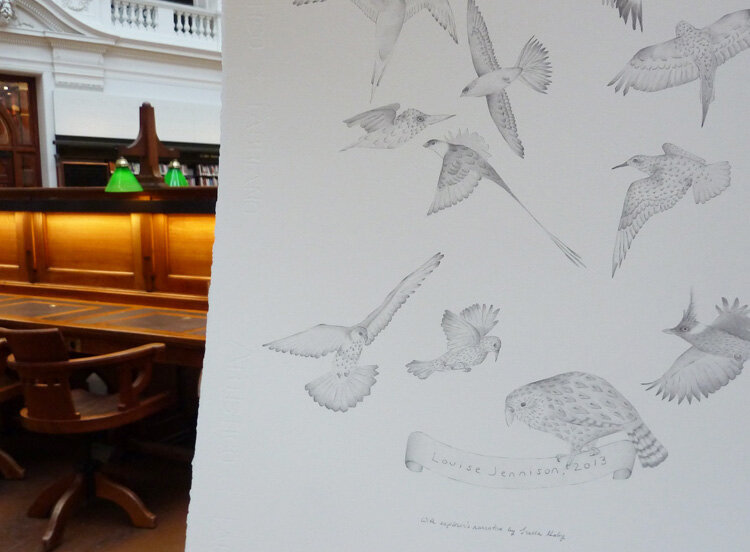

A YEAR OF SOUTHERN HEMISPHERE BIRDS

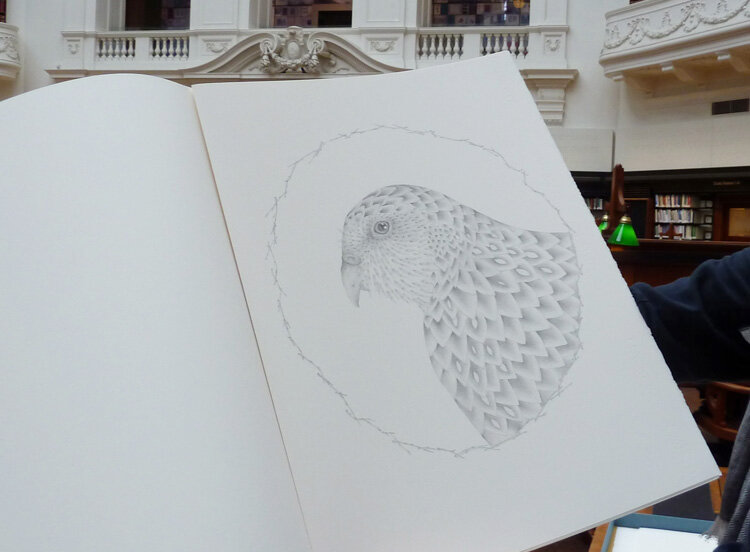

Depicted to scale, each bird, one for every month of the year, is encircled by the food it eats (the Crested Jay by a ring of wasps, the adult and juvenile Southern Boobooks by a mischief of mice, the Grey-rumped Treeswift by a necklace of butterflies from Malaysia), the home it keeps (the Rufous Hornero in her dried mud nest-cum-oven, the Shaft-tailed Whydah on an Acacia branch), and the things it does (the sticks cleared by the Kakapo to make a stage from which to woo a mate).

Louise Jennison

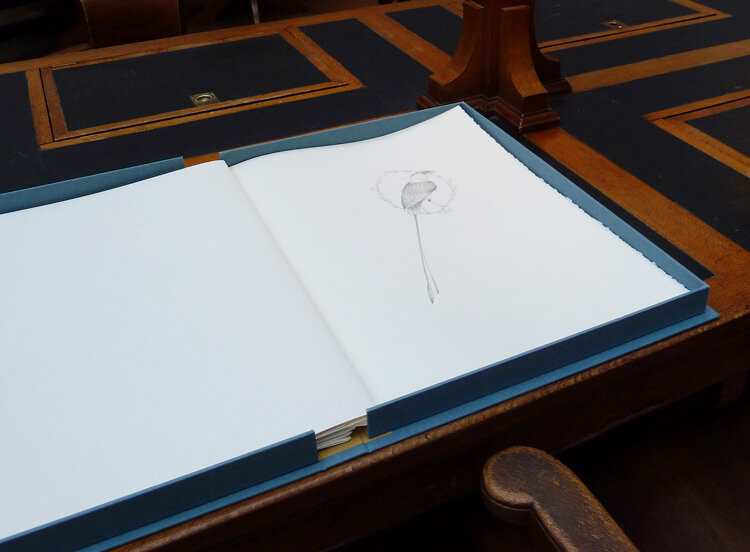

A Year of Southern Hemisphere Birds

2013

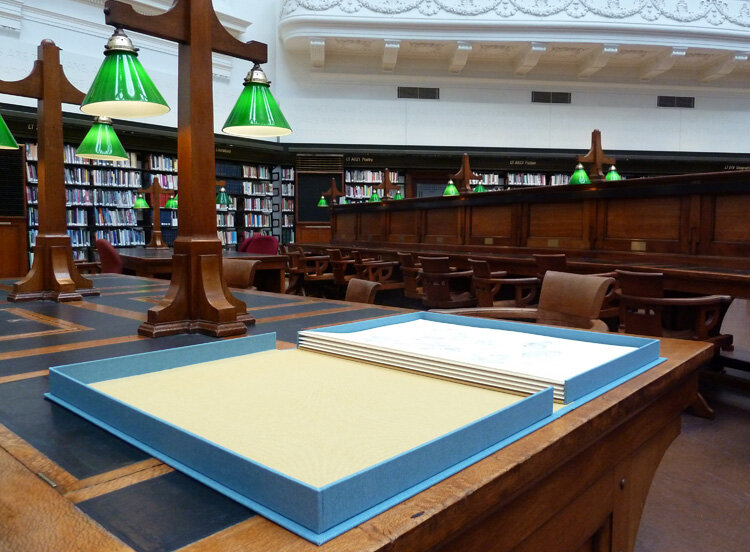

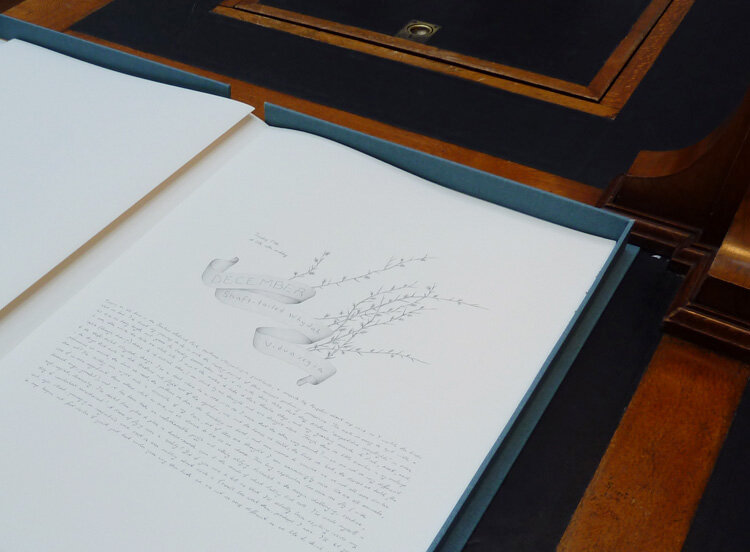

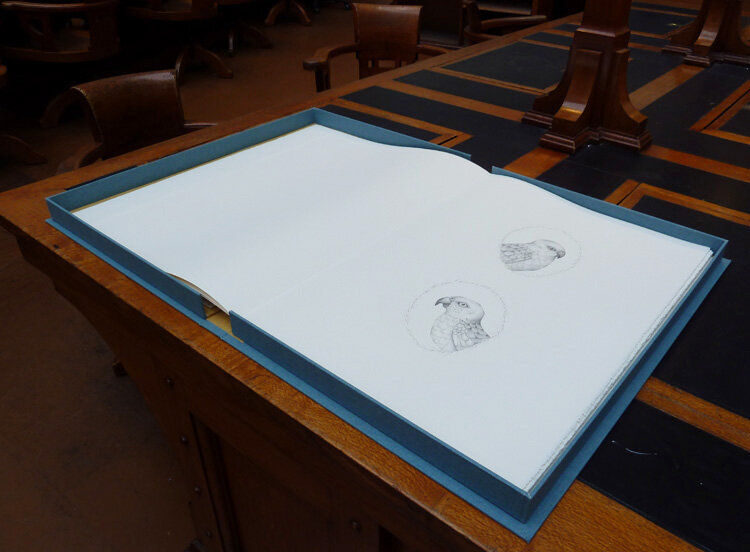

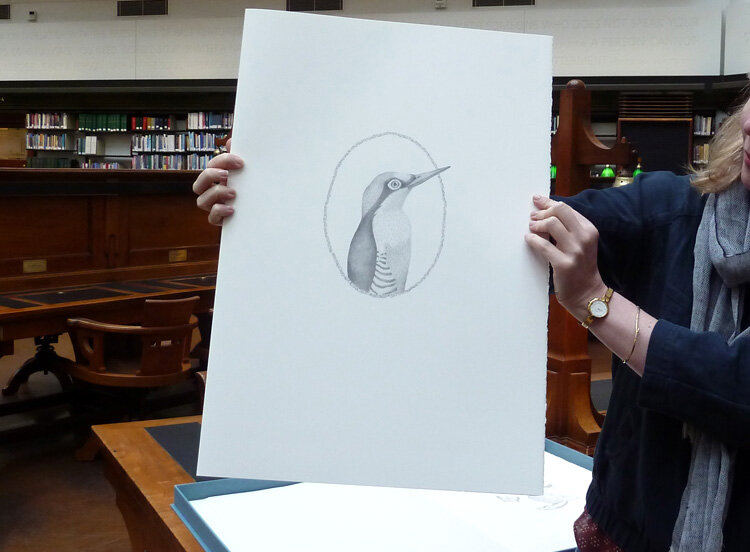

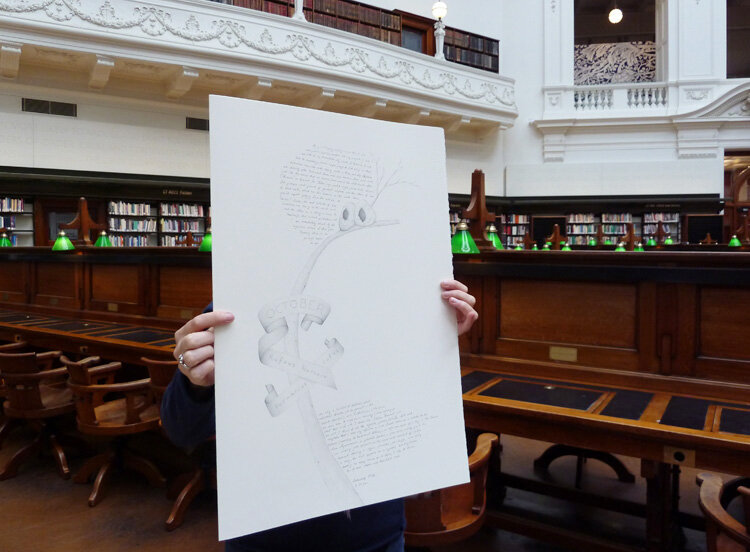

Artists’ book, unique state, pencil on Fabriano Artistico 300gsm traditional white hot-press paper

With explorer’s narrative (by Gracia Haby)

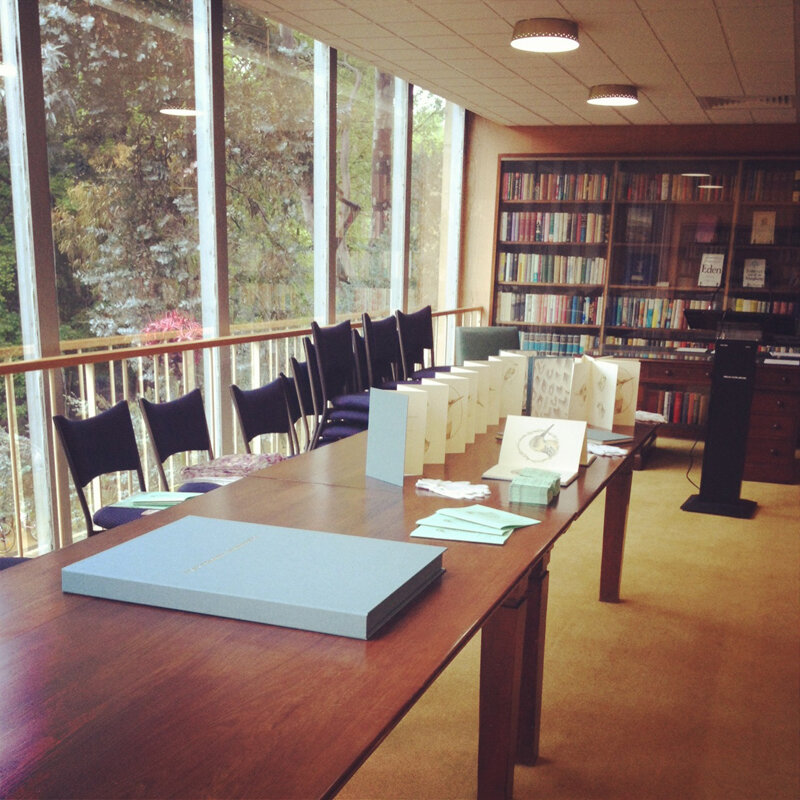

Housed in a linen Solander box (bound by Whites Law Bindery)

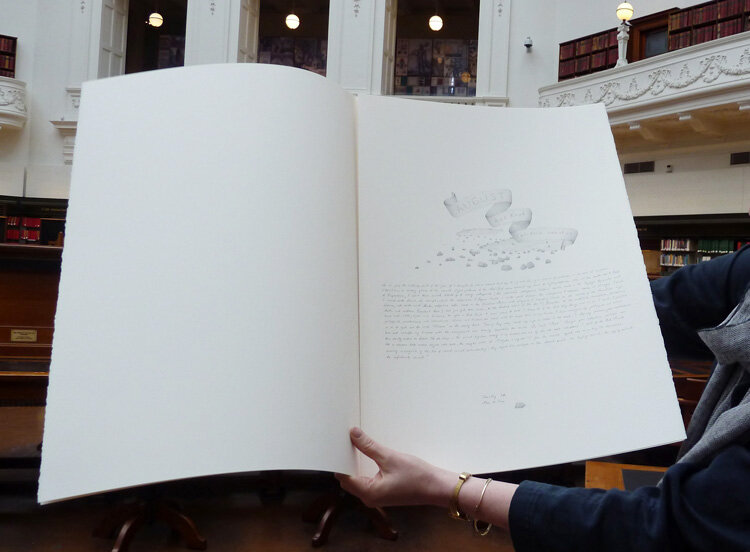

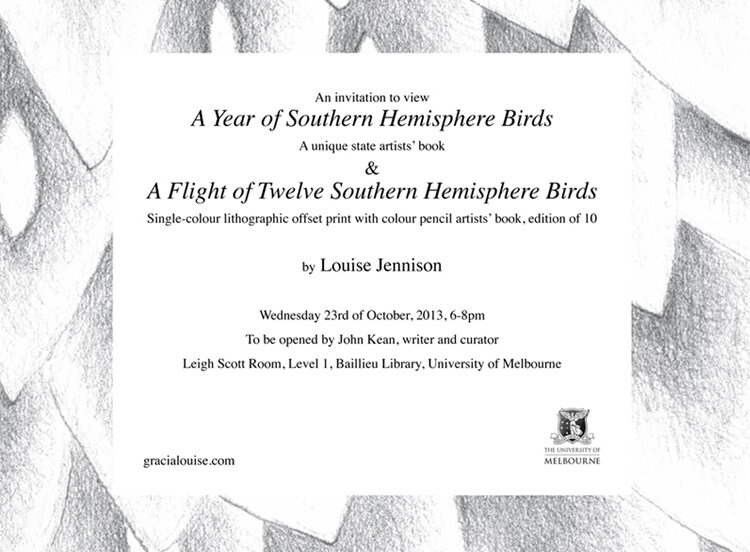

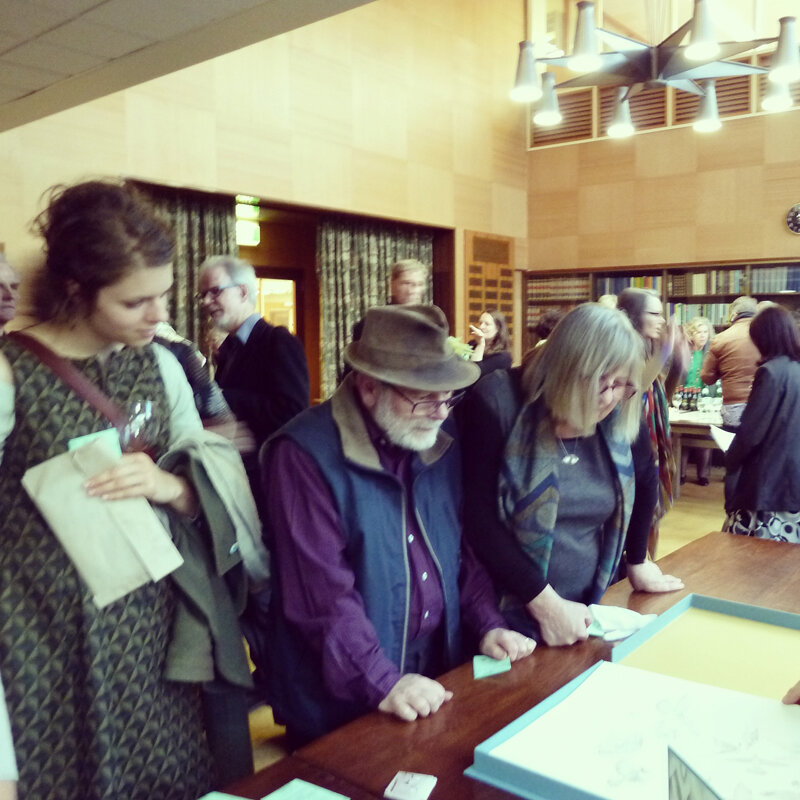

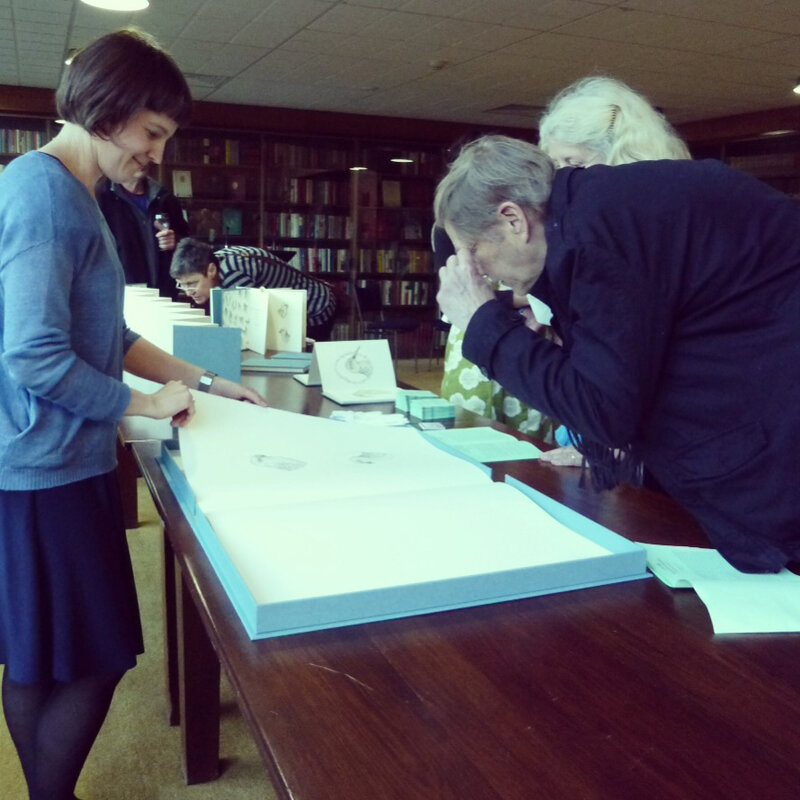

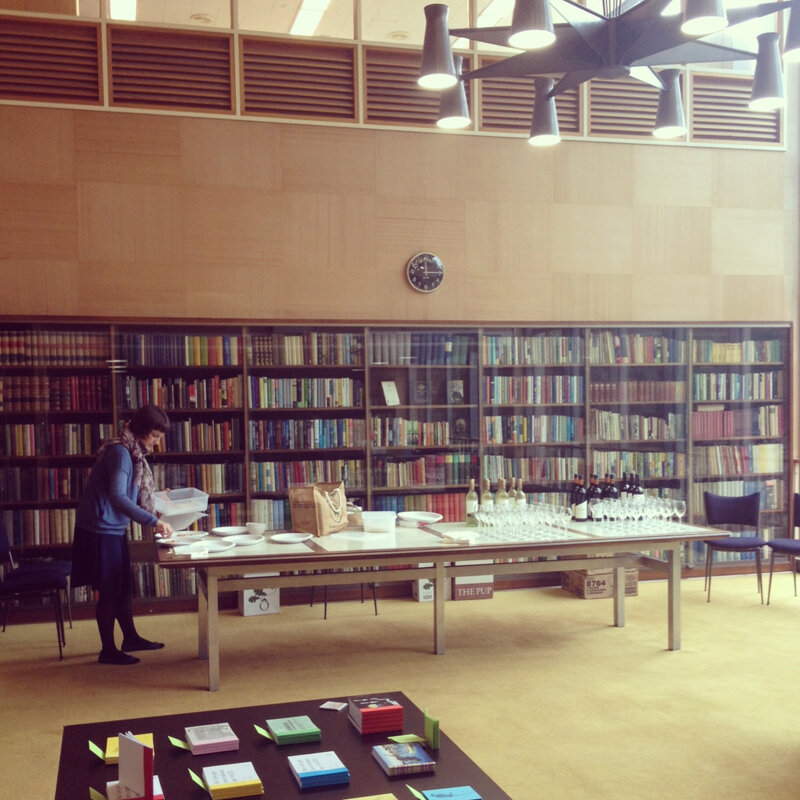

This artists’ book was officially launched on Wednesday the 23rd of October in the Leigh Scott Room of the Baillieu Library, University of Melbourne, 2013. It was opened by writer and curator, John Kean.

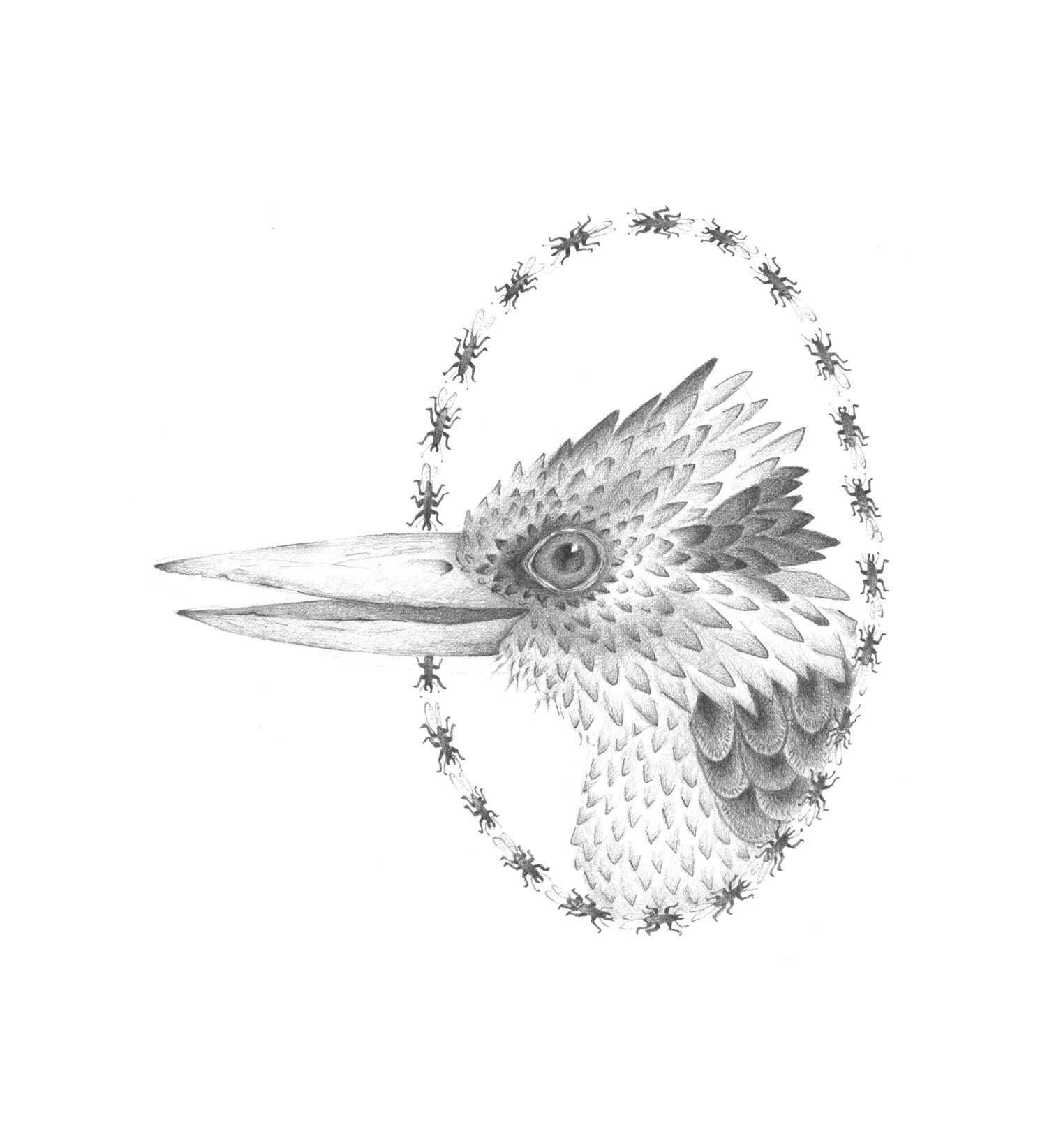

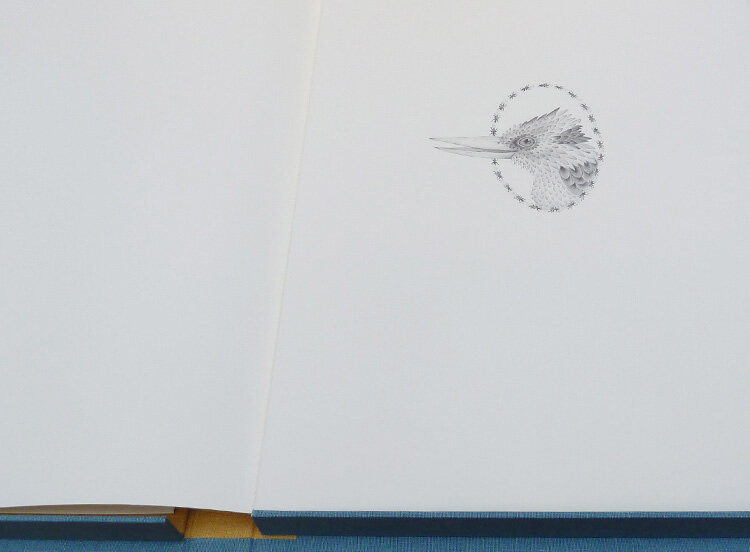

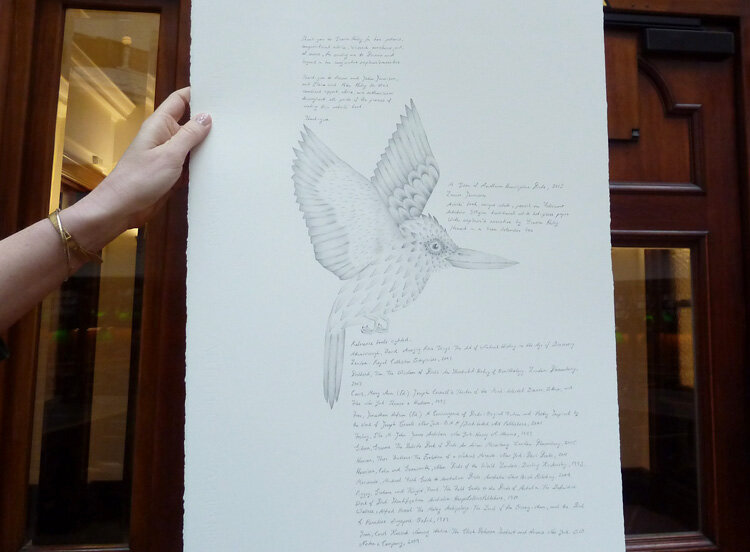

JANUARY Yellow-billed kingfisher (Syma torotoro)

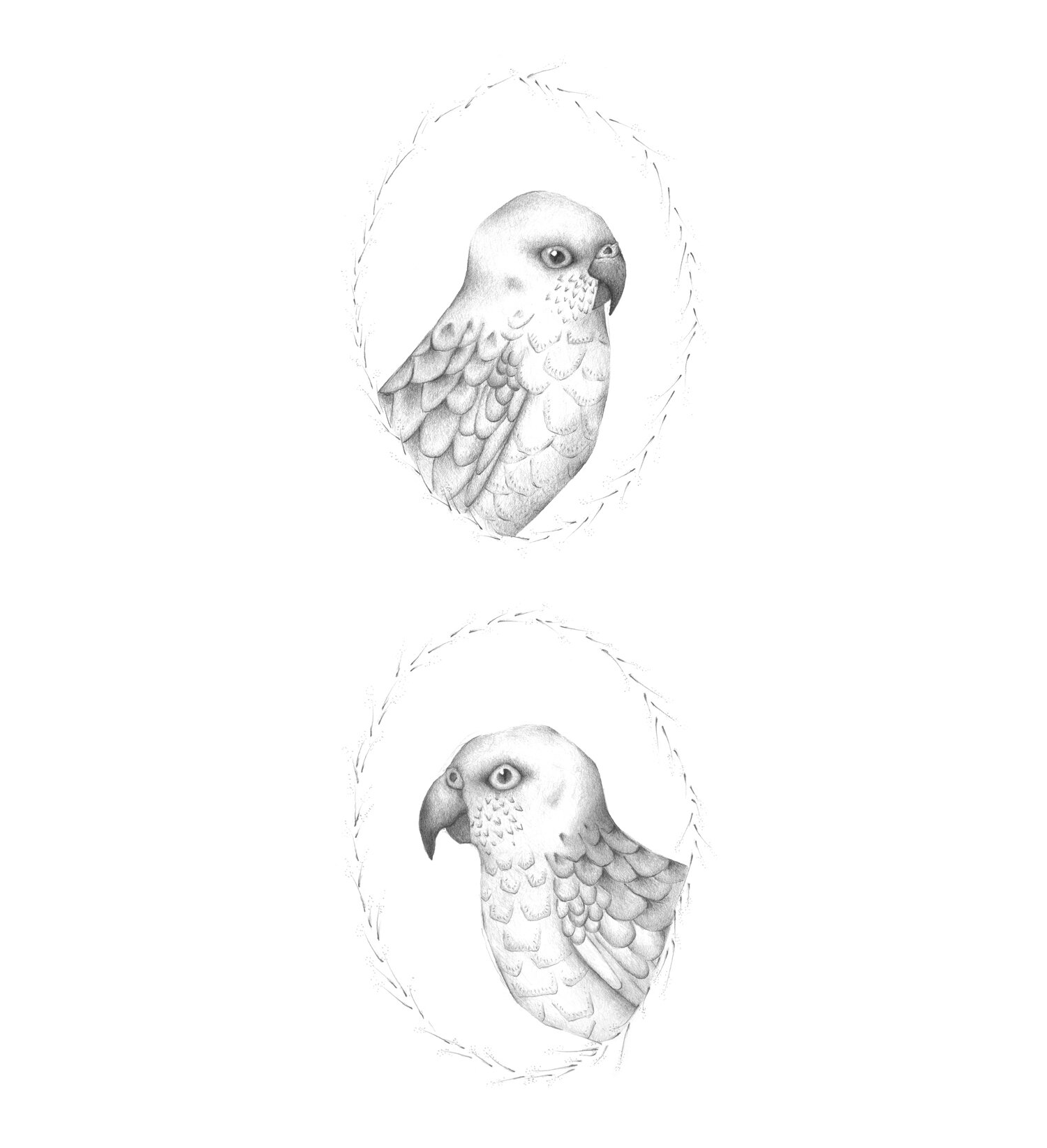

FEBRUARY Red-rumped parrot (Psephotus haematonotus)

MARCH Crested jay (Platylophus galericulatus)

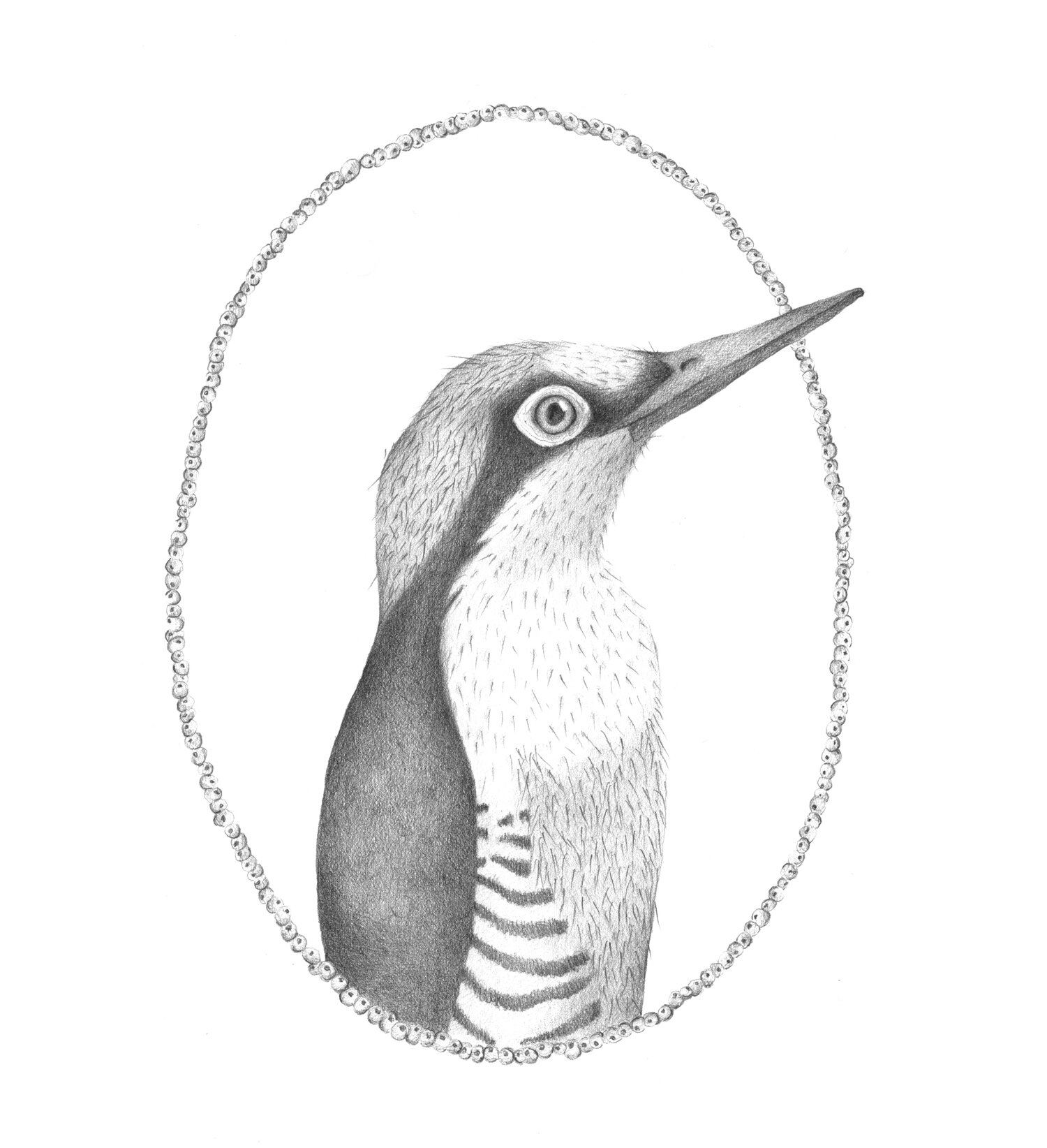

APRIL Yellow-fronted woodpecker (Melanerpes flavifrons)

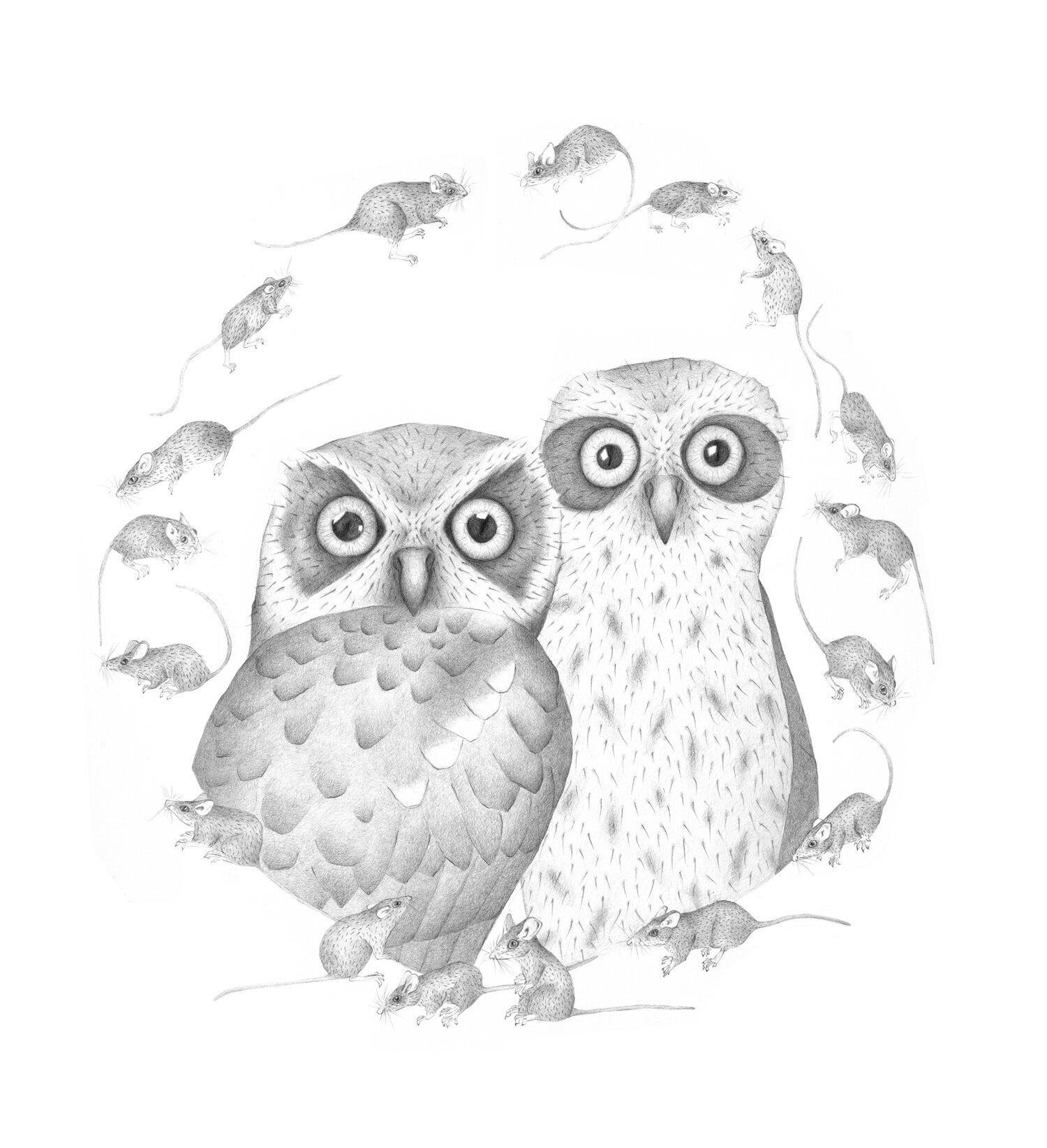

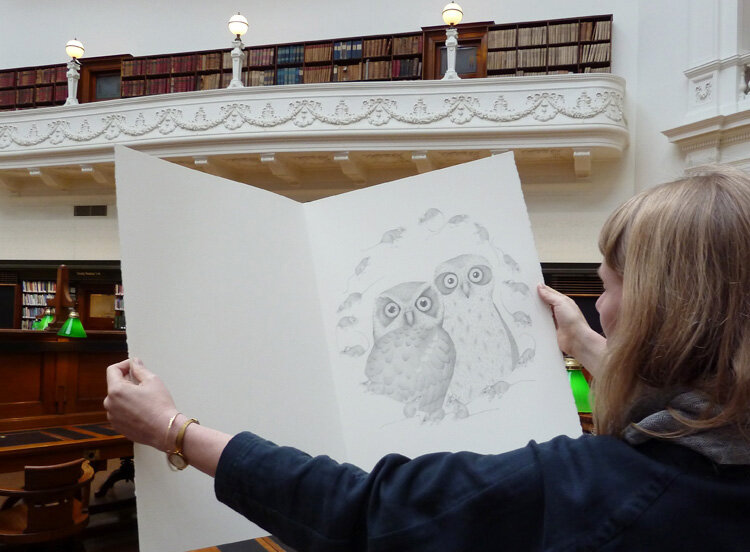

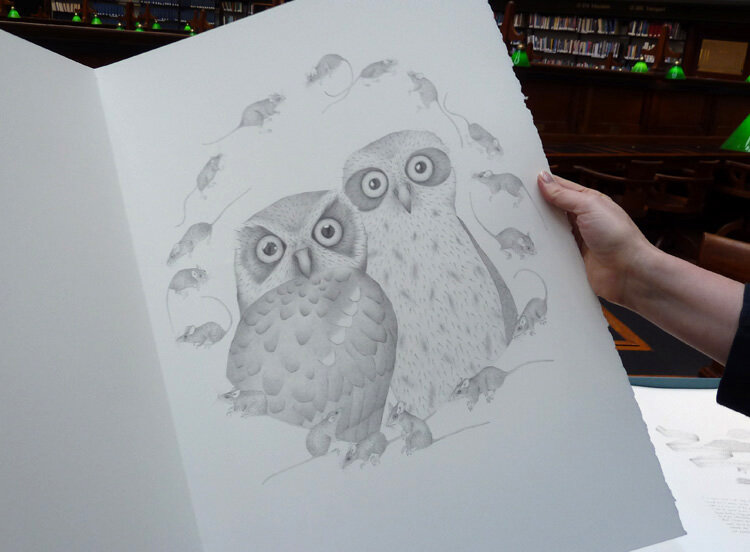

MAY Southern boobook (Ninox novaeseelandiae)

JUNE Grey-rumped treeswift (Hemiprocne longipennis)

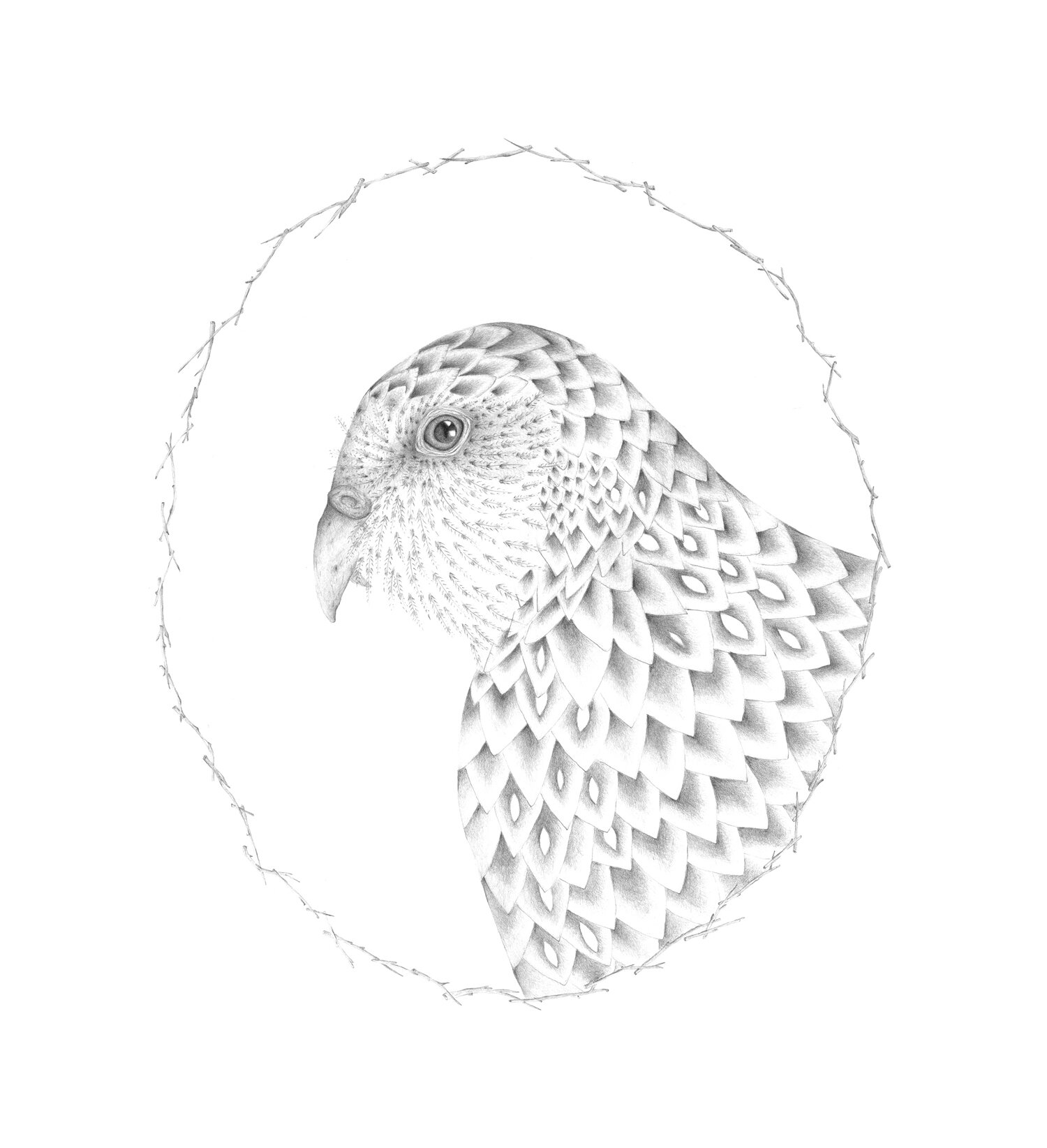

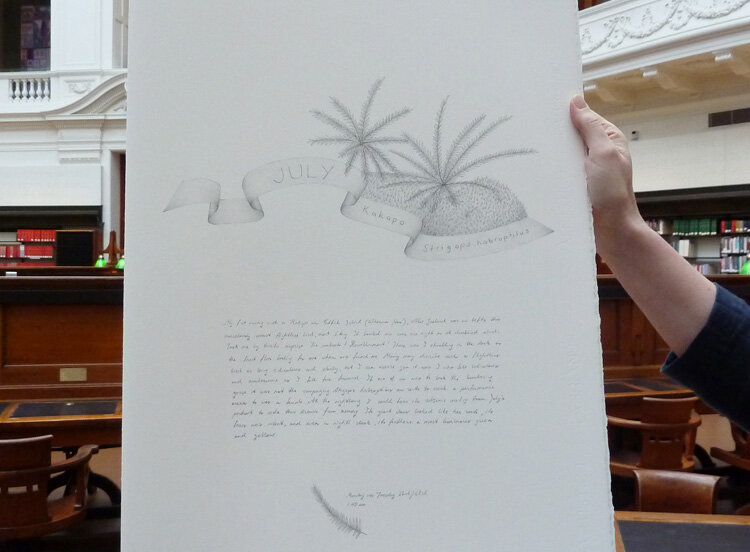

JULY Kakapo (Strigops habroptilus)

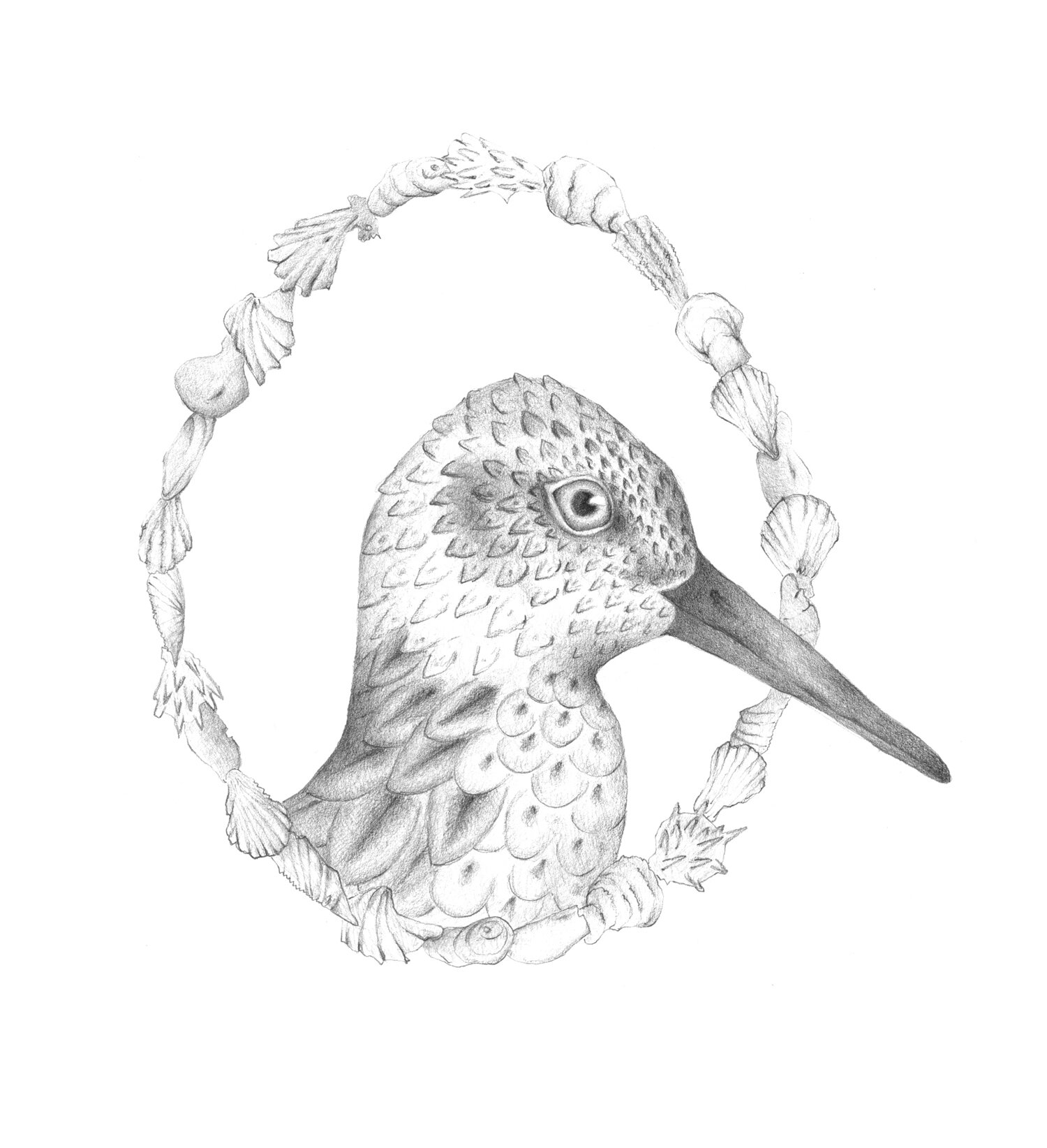

AUGUST Red knot (Calidris canutus)

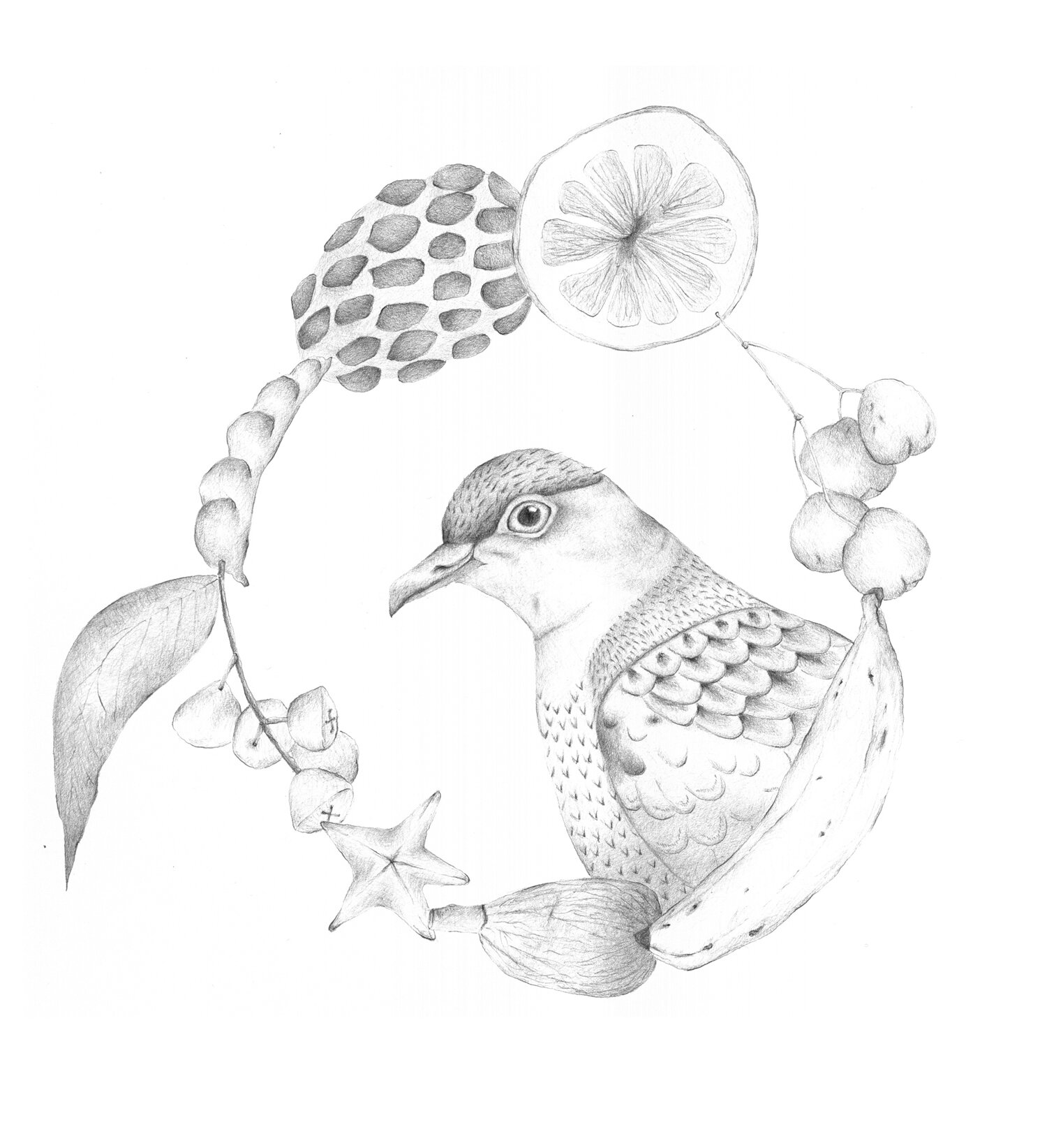

SEPTEMBER Superb fruit-dove (Ptilinopus superbus)

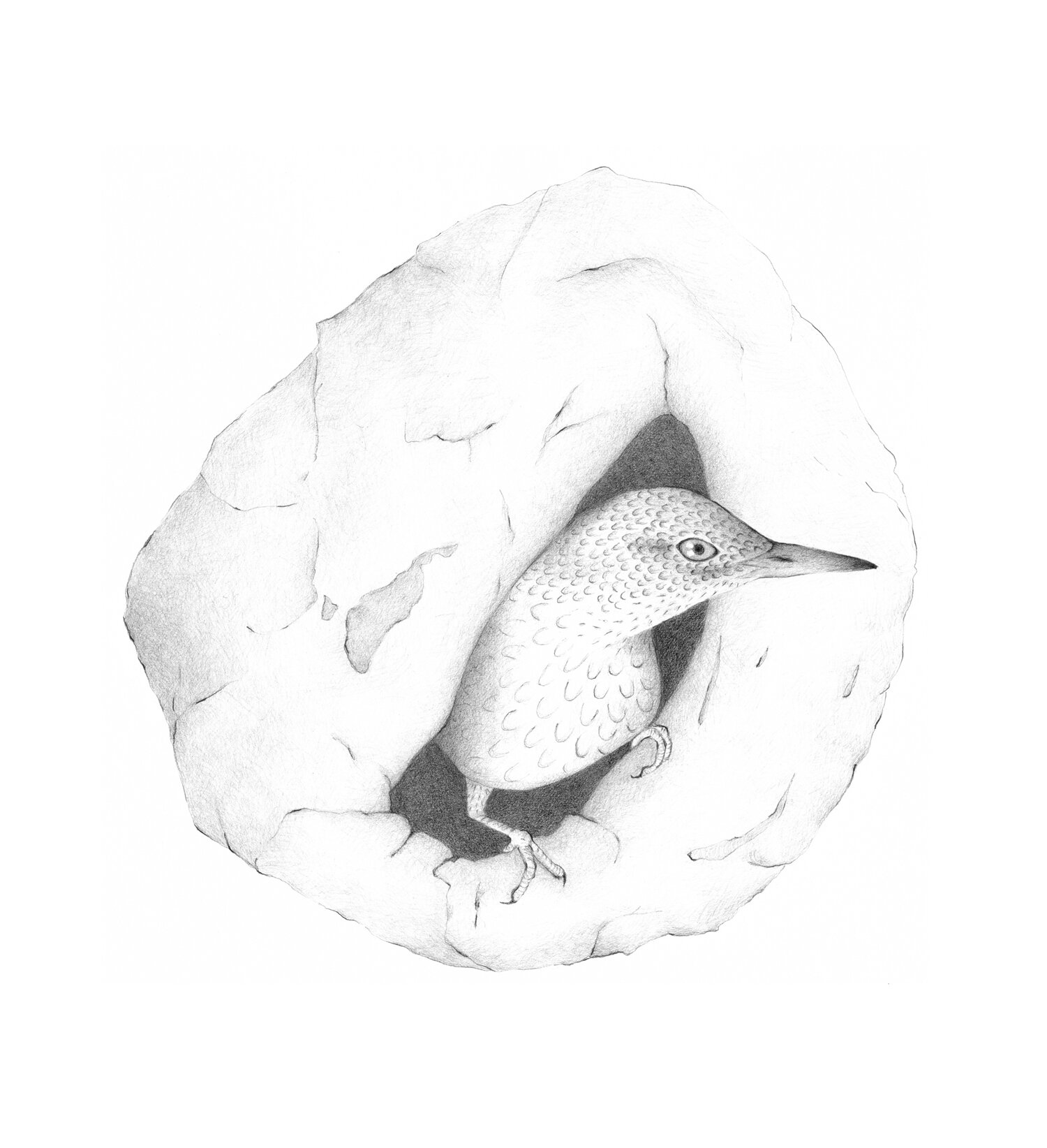

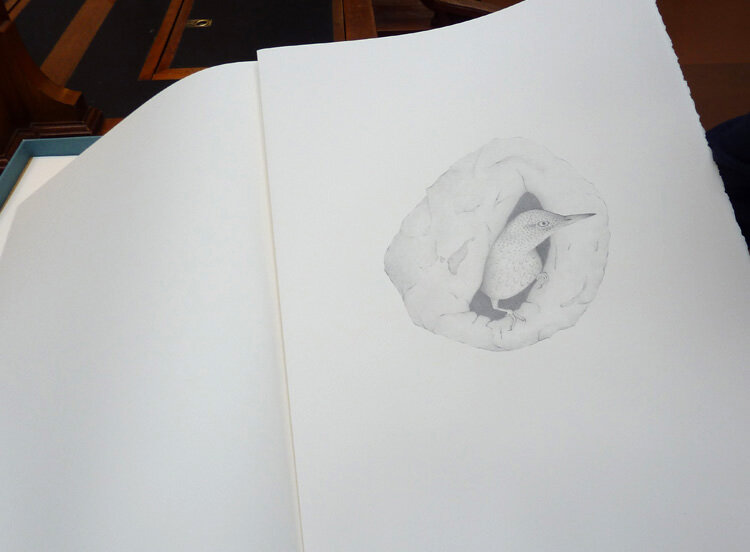

OCTOBER Rufous hornero (Furnarius rufus)

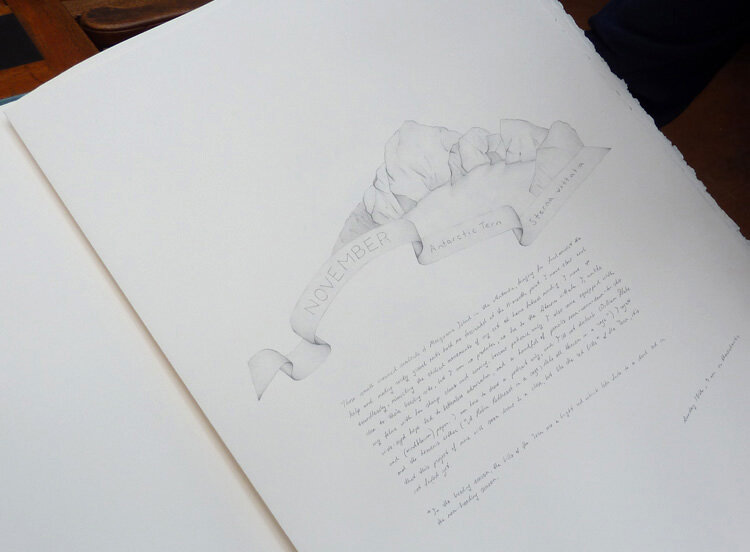

NOVEMBER Antarctic tern (Sterna vittata)

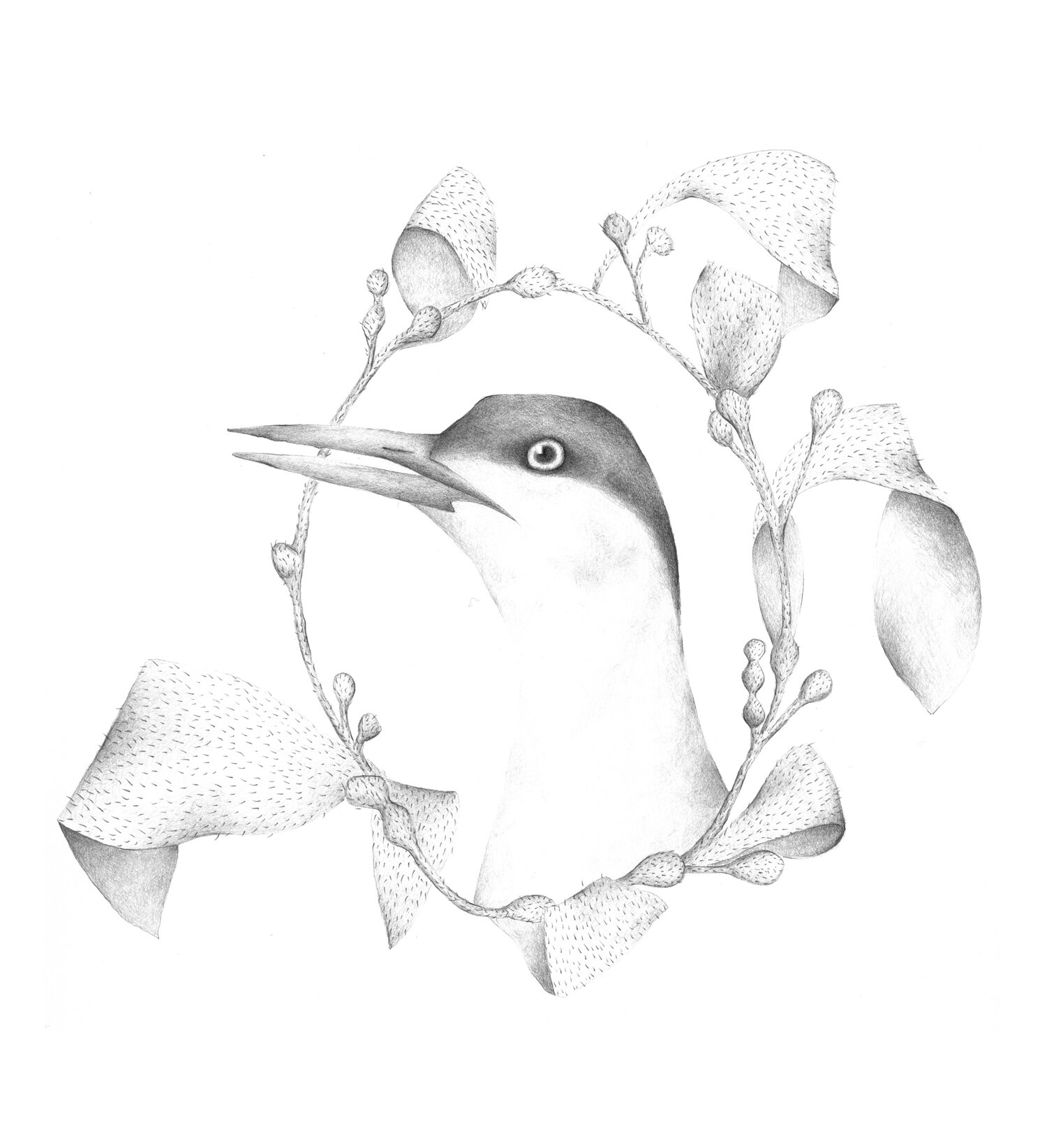

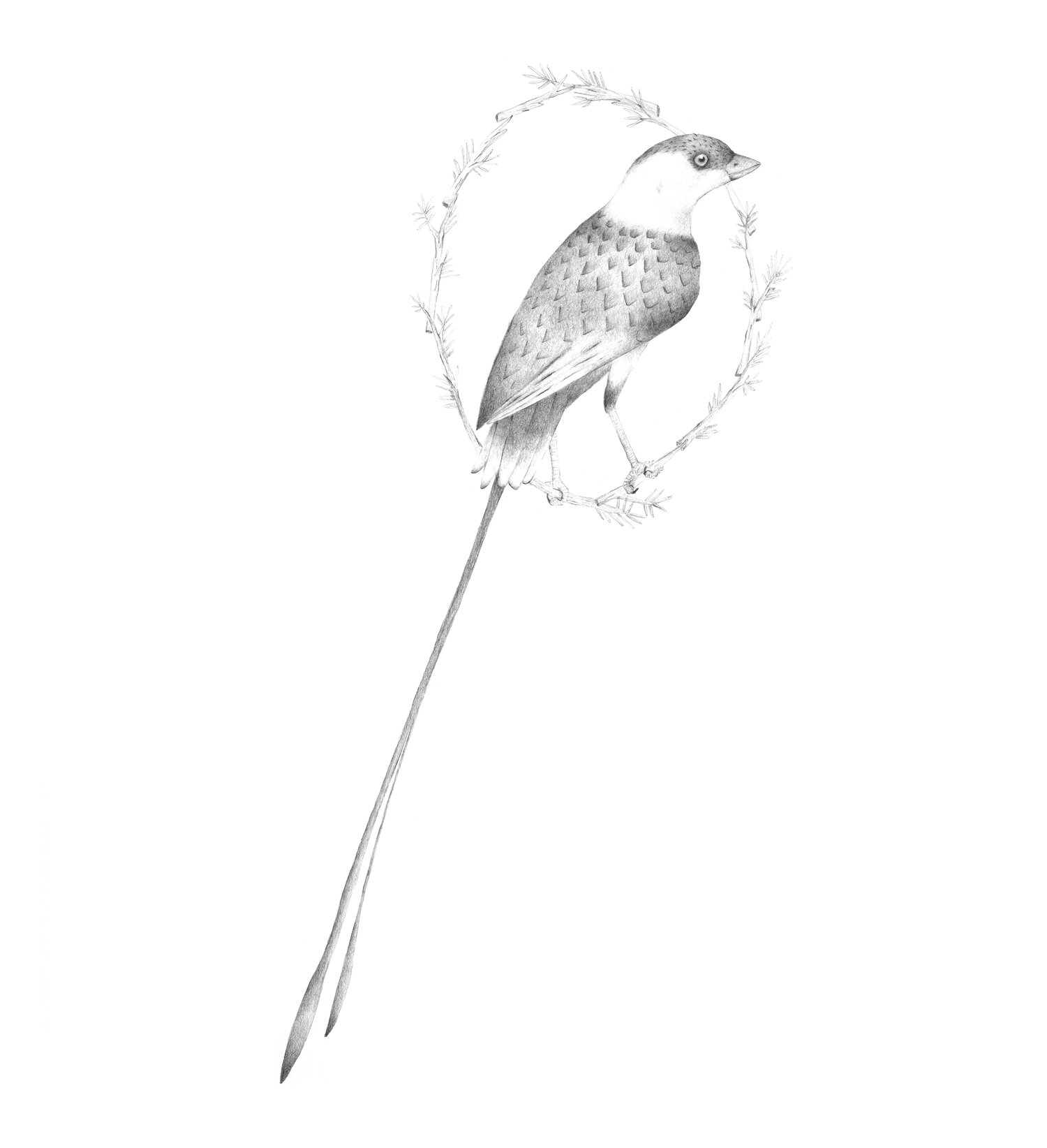

DECEMBER Shaft-tailed whydah (Vidua regia)

In Louise Jennison’s A Year of Southern Hemisphere Birds unique state artists’ book, twelve birds are brought together and their portraits hand-drawn for posterity. Depicted to scale, each bird, one for every month of the year, is encircled by the food it eats (the Crested jay by a ring of wasps, the adult and juvenile Southern boobooks by a mischief of mice, the Grey-rumped treeswift by a necklace of butterflies from Malaysia), the home it keeps (the Rufous hornero in her dried mud nest-cum-oven, the Shaft-tailed whydah on an Acacia branch), and the things it does (the sticks cleared by the Kakapo to make a stage from which to woo a mate). Alongside written facts and a pocket of environment drawn, these portraits in book form bring together a year’s worth of work. Housed in a Solander box made to scale of turquoise linen with an interior lined gold (to recall the wings of parrots et. al.), this work is both homage to Audubon and his ilk, and something more.

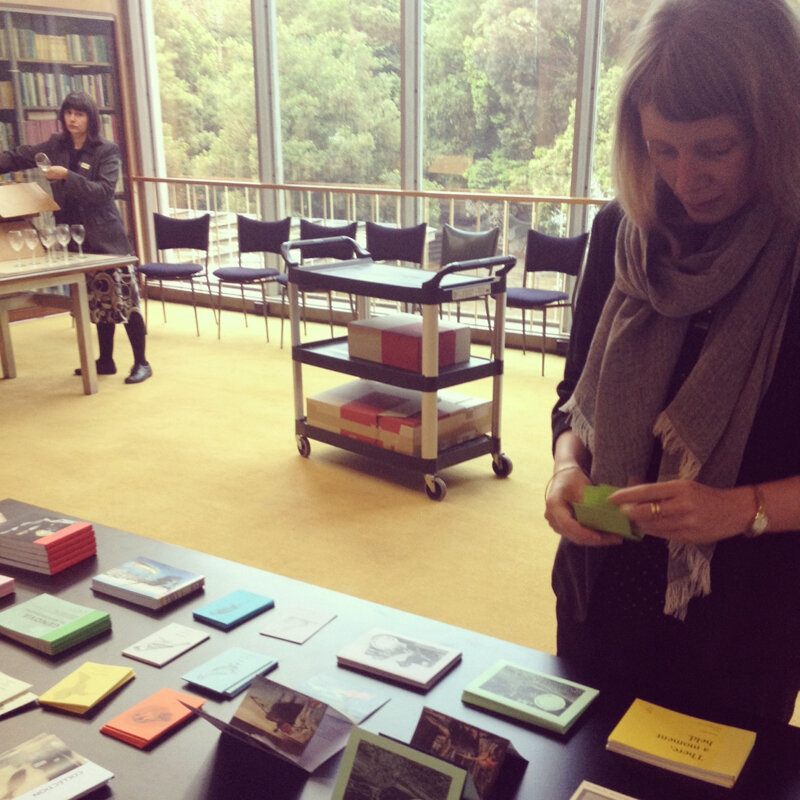

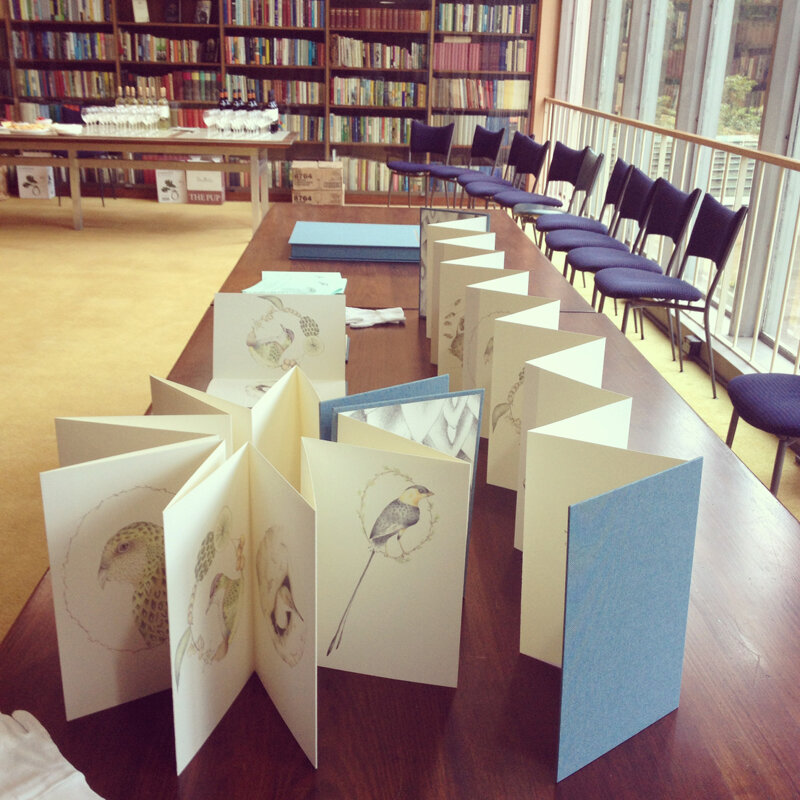

In companion to this, A Flight of Twelve Southern Hemisphere Birds, a concertina bound artists’ book of smaller scale, and an edition of ten. In this edition, the portraits previous are hand-coloured by pencil, rendering the Yellow-billed kingfisher, Red-rumped Parrot, Superb fruit-dove, and the Yellow-fronted woodpecker luminous and (relatively) true.

In both works, the bird is shown as living creature to respect and to be in awe of, and as something not so very different to ourselves. The homes we build, the lives we lead, the desires we hold, the foods we eat, the patterns we form, the knowledge we hold, and our means to survive: are we all more similar than not?

A Year of Southern Hemisphere Birds is in the collection of the State Library of New South Wales.

﹏

RELATED LINK,

A FLIGHT OF TWELVE SOUTHERN HEMISPHERE BIRDS

RELATED POSTS,

FLYING IN THE LIBRARY

LET LOOSE IN THE DOME

SQUEEZING IN AT FIRST WAS HARD, BUT I'VE FOUND A PLACE WHERE I CAN HIDE

A BOOK IN THE LIBRARY

A VERY FINE LAUNCH IN THE SOUTHERN HEMISPHERE

IN THE LEAD-UP TO AN ARTISTS' BOOK LAUNCH

A FEATHERED EXPLORER'S HAT

A MEDIUM SIZED BIRD WITH A WINGSPAN EQUAL TO THAT OF A 30CM RULER

A LAUNCH DRAWS NEARER

FEATHERED INVITATION

WITH HEAD IN THE SAND INDEFINITELY, THIRTEEN SPRING VIEWS

GREY-RUMPED TREESWIFT (A MIFF 2013 INTERMISSION, III)

YELLOW-BILLED KINGFISHER (A MIFF 2013 INTERMISSION, II)

KAKAPO, SPLENDID KAKAPO (A MIFF 2013 INTERMISSION, I)

SOUTHERN BOOBOOK DUO

A PAIR OF RED-RUMPED PARROTS

SEPTEMBER BELONGS TO THE SUPERB FRUIT-DOVE

FROM SWANS TO YELLOW-FRONTED WOODPECKERS

A YEAR OF SOUTHERN HEMISPHERE BIRDS WITH ITS SUPERB FRUIT-DOVES AND RED-KNOTS AND A KAKAPO TOO

A YEAR OF SOUTHERN HEMISPHERE BIRDS

Explorer’s narrative for Louise Jennison’s A Year of Southern Hemisphere Birds, and A Flight of Twelve Southern Hemisphere Birds

JANUARY

Yellow-billed kingfisher (Syma torotoro)

WEDNESDAY 16th

1.50 PM

As I sit here concealed by leafy tropical canopy in Lae, a remote part of Papua New Guinea, I am thinking that my hastily formed idea might just be a little mad and most decidedly ill formed. When we spoke at Christmas of our plans for the forthcoming year, little did I imagine myself actually acting upon them, yet here I am, explorer’s hat on my crown, awaiting sighting of the Yellow-bellied Kingfisher*. There are worse ways to spend one’s January, and, some would rightly argue, there are better ways to spend one’s January, and, there is, it transpires, my way to spend the first month of the year, with binoculars pressed to nose bridge, ears on alert for the whistling trill of the Kingfisher. A medium sized bird with a wingspan equal to that of a 30cm ruler, they are apparently quite common both the local guides and printed guidebooks assure me, though my experience seems thus far to be the exception to the rule. The long hot days of summer draw me a cantankerous figure (this, the ill formed part to my plan I earlier referenced), and I wonder if I will be able to manipulate the mantle of Twitcher to fit my shape. The mosquitoes are holding a wedding party on my right leg and a conference on my left, and on my forearms, their local government is in session. I am being bitten, pricked, and drained, and all in name of cataloguing twelve southern hemisphere birds, one for each month of the year. I wait, pencil in hand, ready to draw for you this stocky little bird whose very sighting will turn my seasonal rancour on its head. (The Kingfisher is known to favour feasting upon large insects, earthworms and lizards so am draping them about my person. Is a lure to cheat?)

* Drawn here surrounded by a ring of termites. It is in the abandoned chambers created by arboreal termites that the Kingfisher makes its nest, laying between 3 to 4 eggs.

FEBRUARY

Red-rumped parrot (Psephotus haematonotus)

TUESDAY 14th

12.30 PM

Back now in familiar environs, in North Fitzroy’s Edinburgh Gardens, Victoria, with arguably a slightly more modest aim: to sight the sedentary Red-rumped parrot in the month that holds St Valentines. You can keep your winged cupids and doves and heart motifs, for me I crown the Red-rumped parrots who are known to mate for life February’s bird to sight, draw, and pay homage to upon the page. And there, sighted just outside my front door, two in the open grassland. They hold remarkably still as I draw their portraits. How obliging the warm day and love has made them. And as I listened to their two- syllable whistle I thought I did hear Chaucer’s words ‘parroted’, but then again it might have been the heat playing tricks upon my ears or Cupid’s arrow in my cheek. As nearby trees appeared to sport leaves that looked like love hearts from the distance, I knew it was time to make good my retreat indoors.

For this was on seynt Volantynys day Whan euery bryd comyth there to chese his make.

[“For this was on Saint Valentine’s Day, when every bird cometh there to choose his mate.”]

Parlement of Foules, a 699-line poem by Geoffrey Chaucer, written in 1380–90

MARCH

Crested jay (Platylophus galericulatus)

FRIDAY 8th

Nearing 9 PM

The arrival of autumn finds me in the Apo Kayan Highlands of Borneo, looking for the aptly named Crested jay in the forest. Fine millinery a quietly kept weakness of mine; I was lured here (and not the other way around, as per January’s Field Notes) by their elegant tufted appearance. By no means flamboyant or garish, the Crested jay is a study of refinement and the third bird I seek. One of many birds whose numbers are decreasing owing to habitat lost to logging and gobbled up by agricultural needs, I, like Wallace, and Audubon, Gould and his hummingbirds, and countless others before me, wade through the green. My goal fixed: to draw my subject in their natural environment surrounded by those very things that sustain them. Assuming temporary ownership, ‘my’ birds are my ‘subjects’ not my ‘specimens’ tied up and bagged. I’m not here to draw one from specimens pieced together to form a whole. The descriptions of the poor Birds of Paradise in Wallace’s The Malay Archipelago, my current bedside reading matter with oft grisly descriptions, still in my mind: “The poor creature would make violent efforts to escape, would get among the ashes, or hang suspended by the leg till the limb was swollen and half-putrefied, and sometimes die of starvation and worry. One had its beautiful head all defiled by pitch from a dammar torch; another had been so long dead that its stomach was turning green.” No, I tell myself, I am here to draw a portrait of one and from one perhaps know more of a whole. Upon arrival here, the Iban people tell me they have long classed the Crested jay as an Omen bird (commonly called Bejampong or Rain Bird) capable of foretelling how your crops will fare, your married life will flourish, and the prosperity of your children. All of this I, as novice, knew less than little of, my choices made in discussion with both my heart and gut. And so I find myself somewhat out of depth but liking the view all the same. If I knew the outcome before I set off, well, there would be little to learn in doing that.

APRIL

Yellow-fronted woodpecker (Melanerpes flavifrons)

MONDAY 22nd

1.45 PM

You find me now in the Upper Bermejo River Basin in North West Argentina, in search of the fruit-eating Yellow-fronted woodpecker. Four months into my task of cataloging a varied winged twelve, I am looking the seasoned Twitcher. I cannot warble off the facts of my peers with apparent ease, but my attire has the role well pegged and, as we all know, appearance is a great way to half of a thing. Look the part and they’ll never know, the Kingdom rule. Besides which, in the quiet of the hide, chatter is minimal. We wait for our self-nominated birds to appear. We wait, soundlessly. All noise comes from the forest around us that threatens to ensnare us and make of us its lucky charm. Earlier in the day as the hour drew close to lunchtime, my stomach rumbled with such ferocity that it was ordered to hush. ‘But how?’ I mimed with shrug-shoulder movement to my colleagues closely perched. I proceeded to rummage (to my ears) noiselessly in my rucksack for a cracker to quietly in small pieces suck, but this too, this was deemed too much. Evicted from the hide, I left in bad temper. I let my footfall fall heavy, breaking twigs underfoot, looking the very picture of petulant child. Once I’d cooled and taken on regular form once more, I sat down on the forest floor and made a picnic of two (crunch! crunch!) crackers. Upon doing so an inquisitive Yellow-fronted Woodpecker appeared. It perched upon my open rucksack and seemed to wish to join me. Together, we feasted, before he posed for me for several hours with his red cap resplendent. Five points to the blundering novice, this triumph is sweet and chance is my new master.

MAY

Southern boobook (Ninox novaeseelandiae)

SUNDAY 19th

10.15 PM

Tiny little Ninox novaeseelandiae of mainland Australia, Tasmania, and the coastal islands. Tiny little Ninox novaeseelandiae, lover of the open desert and the dense forest. Why, you’ve charmed your way into May placement. Sighted nesting in a tree hollow one night, I fell that hook, that line, that sinker, for your great big eyes and your small frame. Though your love of the rodent as delicacy is one I cannot with my palette come to appreciate, I admire you all the same. You talk to me of their paper fine ears tasting like the finest morsel and I find myself wincing ever so slightly. But no love was ever smooth in her course, and so I find myself both drawn closer and repelled. Caught in your talons, a small grey tail and I think of childhood tales (of Anatole the mouse with the expert knowledge of cheese, and Ratty and his beloved riverbank). And so, my handsome little tiny Ninox novaeseelandiae I will draw your portrait with you and your young encircled by a ring of mice. A mischief of mice for the two of you, only please, pray, make their demise swift. (In writing this love missive to a Boobook I realize that the winter isolation is already taking its toll. I am metamorphosing into a true Twitcher before your very eyes. My mannerisms have quite altered, and I fear all forms of normal society may well be closed to me forever now. But what for that cared the besotted, mania-bitten. What indeed.)

JUNE

Grey-rumped treeswift (Hemiprocne longipennis)

TUESDAY 11th

3.30 PM

In a mangrove forest in the Malay Peninsula, I spot the easily detectable Grey-rumped treeswift from a distance. The tail is like a pair of long-bladed scissors, and the inclement weather is on my side. As they perch on the twigs for a rest, showing me same cheek as Gould, I draw the portrait of this non-migrant. For their generosity, a halo of butterflies (Rajah Brooke’s Birdwing (Trogonoptera brookiana), Common Lascar (Pantoporia hordonia hordonia), The Wizard (Rhinopalpa polynice), Wavy Maplet (Chersonesia rahria), Horsfield’s Baron (Tanaecia iapis)). My fascination with birds has struck me quite late and J. Ruskin’s lament, when he mulled over a life he deemed ‘wasted’ on mineralogy, echoes my own wilderness steps: “Had I devoted myself to birds, their life and plumage, I might have produced something worth doing”.

JULY

Kakapo (Strigops habroptilus)

MONDAY into TUESDAY 22nd / 23rd

1.40 AM

My first meeting with a Kakapo on Codfish Island (Whenua Hou), New Zealand was as befits this marvelously robust flightless bird, most fitting. It bowled me over one night as it clambered about. Took me by terrific surprise. The ambush! Bewilderment! There was I stumbling in the dark on the forest floor looking for one when one found me. Many may describe such a flightless bird as being ridiculous and stocky, but I can assure you it was I who felt ridiculous and cumbersome as I fell face forward. If one of us was to look the lumbering goose it was not the rampaging Strigops habroptilus en route to create a performance arena to woo a female. All the nightlong I could hear its subsonic mating boom. July’s portrait to scale thus drawn from memory. Its giant claws looked like tree roots, its focus was intent, and even in night’s cloak, its feathers a most luminous green and yellow.

AUGUST

Red knot (Calidris canutus)

THURSDAY 8th

Near to 11 AM

As we pass the halfway point of the year, if I thought for but a moment that my to-ing and fro-ing in search of particular birds was of immense proportions, a cursory glance at the annual flight patterns of the Red knot soon returned my head to right proportion. Now at the south east Gulf of Carpentaria, I await their arrival. Made up of many subspecies (the nominate subspecies Calidris canutus breeds in the Taymyr Peninsula and in central- north Siberia, for example, whilst the subspecies C. rogersi breeds in north-east Siberia; the subspecies C. roselaari breeds at Wrangel Island, Siberia, and north-west Alaska; subspecies rufa breeds in the Canadian Arctic; and subspecies C. islandica breeds on the islands of the Canadian high Arctic and northern Greenland. Have I lost you yet, dear reader, to the factual whirl of the fan?) Beholden to the mudflats, sandflats, estuaries, bays and inlets, lagoon and harbours, to sight a Red knot I know where to look. I know too of the food they fancy, and so as I wait, I prepare gastropods, crustaceans and echinoderms. Worms, and bivalves too. And with too much time on my hands, I have arranged my gastropods and worms so as to spell out the word ‘Welcome’ on the sandy beach. Fearing they may mock my sign or deem it too much, I flip my prearranged crustaceans over and reshuffle my bivalves until the arrangement now loosely resembles the words ‘Eco’ and ‘Mewl’. Though upon reflection, perhaps now this merely renders me foolish. Of all those in the animal kingdom, surely it is humans who are by far the most ridiculous. I wait for the Red knots like a nervous host unsure anyone will come, the mangled words of Nietzsche in my ear: “I fear the animals regard man as a being like themselves, seriously endangered by the loss of sound animal understanding; they regard him perhaps as the absurd animal, the laughing animal, the crying animal, the unfortunate animal”.

SEPTEMBER Superb fruit-dove (Ptilinopus superbus)

SATURDAY 14th

Not long after breakfast 7.10 AM

In the loose vine tangles of the Atherton Tablelands of Tropical North Queensland (the pungency of the air here!), I sight the plump-ly welcoming appearance of the superbly coloured Superb fruit-dove, that most brilliant of seed dispensers. With its purple crown, and burnt marmalade hindneck, this tree-dwelling male marvel is as brilliantly coloured as the plants it favours. Blackberries, lilly-pillies, pittosporums, and figs for this Super Bus/superbus of a bird with its wide gape. I believe it was in my handbook of Southern Hemisphere birds, Volume three, Snipe to Pigeons, that I first came across the to my mind charming fact that all of the fruit-doves (the larger Wompoos and the smaller species the Rose-crowned and the Superb) prefer black-purple fruits. Using ultraviolet colour cues to assess ripeness and suitability, I was struck by the visual this painted in my mind’s eye. The two smaller species will also sip dew from leaves that serve as Mother Nature's crockery. High up in the canopy, the fruit-dove seemed upon reading, and sitting here now still does to some extent, to present like a fairytale superbly coloured.

OCTOBER Rufous hornero (Furnarius rufus)

SATURDAY 19th

4.20 PM

Spring in Uruguay proving warmer than I’d anticipated, but ten months into my project I find I care little of my discomforts. My search for October’s desired bird to immortalize proved simple enough to find owing to their distinctive oven-like nests clearly visible in trees, and atop telephone and electricity poles. Fashioned from mud and manure, these nests look just like the ovens that we humans have named the inhabitants after. (‘Hornero’ is Spanish for ‘Baker’, my pocket-sized phrase book informs.) But perhaps what proved of greatest surprise was the interior of one of these nests, which are far roomier on the inside than you’d expect judging from the outside. A Tardis! Inside, the nest consists of two chambers, one serving as the actual nest and the other as a decoy in order to bamboozle their natural predators, and I am immediately struck by the ingenious nature of this plan. Knowing this it is perhaps easier to see now why a handful of folklores about unfaithful females (to be penned in the second chamber), and Catholicism (the birds are never seen to work on a Sunday) have sprung up about this bird. As I draw the Rufous hornero and her nest I think of all the legends, poems, beliefs, folk and fairytales that in some way reference a bird. Death comes as a rooster to the Cubans (according to traditional folklore); an eagle, an omen of victory in the Chorus from Agamemnon; a peacock’s feather in your house, unlucky you’ll be; and wheeling gulls overhead are the souls made manifest of sailors drowned. Nesting in sagas, parables, paintings, and roosting in song, the bird appears as a symbol awaiting human reading as many times as it does, I like to think, for its own clever and beautiful sake.

NOVEMBER Antarctic tern (Sterna vittata)

SUNDAY 10th

9 AM or thereabouts

Those small crowned seabirds of Macquarie Island in the Antarctic, foraging for food amidst the kelp and making rocky gravel nests hold me fascinated at the 11-month point. I move slow and soundlessly, mimicking the studied movements of my cat at home fortress minding. I move up close to their breeding site, but I am no predator, no foe to the Sterna vittata. I, unlike my feline with her sharp claws and cunning, borrow patience only. I also come equipped with wide-eyed hope tied to bottomless admiration, and a handful of pencils near-warn-down-to-stub and (windblown) paper. I am here to draw a portrait only, and I’ll not disturb William Blake and the heavens either (“A Robin Redbreast in a cage; Sets all Heaven in a rage”). I regret that this project of mine will soon draw to a close, but like the red bills* of the Tern, it’s not faded yet.

* In the breeding season, the bills of the Tern are a bright red which later fade to a dark red in the non-breeding season.

DECEMBER Shaft-tailed whydah (Vidua regia)

TUESDAY 17th

A little after MIDDAY

Creeping on all fours in the Banhine National Park, southern Mozambique grasslands, a concerto by Pergolesi about my ears, as I watch the birds about me feed. I’ve timed my journey to tie in with the breeding period of this curious performing passerine. The male is easy to spot with a tail twice his body length and grown for breeding season alone. And it is with their tails that they perform ‘competitive songflights’ in order to woo, after which the tails are shed. As I await the males to take to their theatre stage, and my yearlong search to find, meet, and capture (though drawing) draws to its natural close, I am struck by one thought and one thought alone. Though there is little similar in my makeup to the Shaft-tailed whydah, though I’ve a beak where he a nose—or do I mean that they other way around?—we are not so very different in the things that make us tick. Feathers and flight out of the equation, are not the homes we build, the lives we lead, the desires we hold, the performances we mount, the foods we need, the patterns we form, the knowledge we hold, and our means to survive: are not we all more similar than not? The midday sun might make a scramble of my brain, but of this one thought I am unwaveringly sure. We are all animals, some of us more magnificent than others. And as such, we all deserve to live as we choose. This long exploration has seen me fly (with borrowed wings, granted), and it has been both an unfathomable puzzle and utterly edifying. Scrawled in the margin: challenging, creative, rough, inspired, illuminating. I’ve darted from place to place in twelve-month span to the sounds of chord tinkling bird call. I’ve made myself a study of wanderlust unrestrained! A dream of flying near a reality! But if you were to tell me that I’d actually been exploring inside my head, eyes closed, journeying on imagination’s wave crest or even ambling about inside a Cornell box work then, perhaps I was. I’ll let you be map keeper and fact checker if you’ll just tuck under your wing this truth: we are not so very different as we like to think we are.

A Year of Southern Hemisphere Birds

Simon Cootes

Collection Development Librarian

Thursday 5th of December, 2013

State Library New South Wales

The State Library has acquired a beautiful set of artists’ books produced by an Australian artist, Louise Jennison.

A Year of Southern Hemisphere Birds is an artists’ book which continues the ornithological tradition of John James Audubon and John Gould. This unique work is a handmade book and has been a year in the making. The work features 12 hand-drawn pencil on paper illustrations of Southern Hemisphere birds, one for each month of the year. The species depicted include the Yellow-billed Kingfisher, the Red-rumped Parrot and the Southern Booboo. Each bird is shown surrounded by images of its food and habitat and the things which it does. The images of the birds are accompanied by Gracia Haby’s explorer’s narrative which provides a prose description of each species. The work portrays birds as creatures similar to humans in the way in which they build their homes and lead their lives.

A Flight of Twelve Southern Hemisphere Birds, is a companion volume to this work. Flight reproduces the portraits from the original work but in each portrait the bird has been hand coloured. Flight is published in a concertina format which folds to form a volume with two cloth bound covers. The Library’s copy is one of only ten published.

The Library holds a rich collection of artists’ books which celebrate the book as an objet d’art and these two books are an excellent addition to this collection.

A Year of Southern Hemisphere Birds is located at X/82.

A Flight of Twelve Southern Hemisphere Birds is located at H 2013/7234.